Image credit: Lyndsey Jenkins / Royal British Columbia Museum and Archives

Missive from a militant: testimony from the first British suffragette revealed

A previously unknown letter from Annie Kenney, the working-class activist who became the first woman imprisoned for campaigning for the vote, is due to go on public display for the first time after being uncovered by Oxford historian Dr Lyndsey Jenkins during her research.

Revealing the personal impact of this iconic political protest, the letter sheds new light on the first act of militant suffrage and is an exciting contribution to this year’s centenary celebrations of the first women gaining the right to vote in Britain.

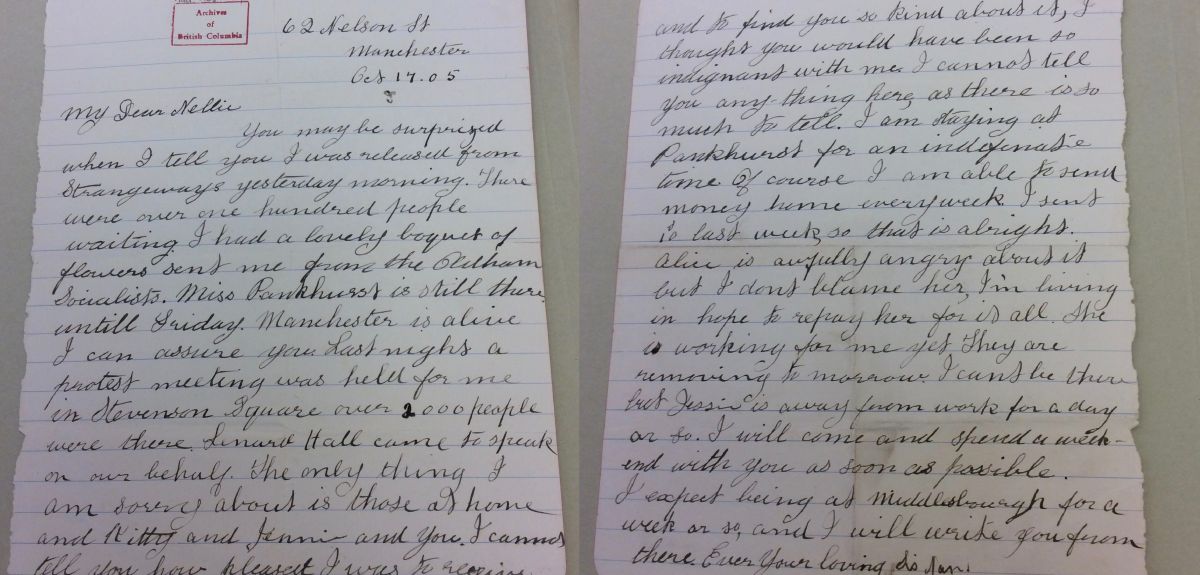

Written from the Pankhurst family home at 62 Nelson Street, Manchester, the letter was sent from Annie Kenney to her sister Nell in October 1905, informing her that ‘you may be surprised when I tell you I was released from Strangeways [prison] yesterday morning’. The letter offers an intimate insight into the complex and competing emotions that Annie experienced as she left prison. She expresses delight at the impact her unprecedented act had made in the local community and her gratitude at the support from most of her family, but also records how another sister Alice, was ‘awfully angry’ about the incident.

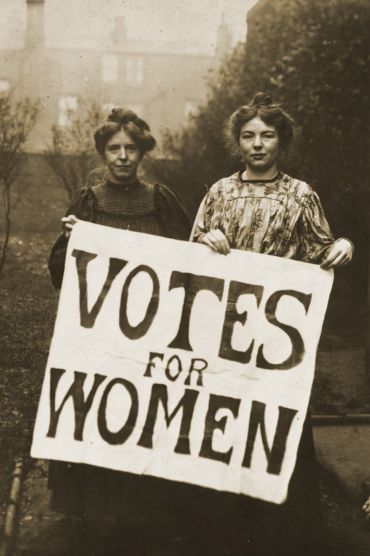

Annie had been sent to jail after she and Christabel Pankhurst had attended a political meeting demanding to know from minister Sir Edward Grey: ‘Will the Liberal Government give votes to women?’ The speaker refused to answer, and the women were thrown out of the hall before both being jailed after Christabel Pankhurst spat at a policeman. The incident is now widely regarded as the first militant action, and the women became instantly famous around the world, attracting huge public sympathy. With the first use of the demand ‘votes for women’ on a placard, the two women created one of the most memorable political slogans of all time, kick-starting a revolution.

The letter has lain unknown for more than a century. Nell Kenney later moved to Canada, and the document was for many years catalogued with general correspondence in the British Columbia Archives in Victoria. It was listed only as part of a collection belonging to Sarah Ellen Clarke, Nell’s full and married name, and, as such, had until now escaped wider attention. It was recently located by Dr Jenkins, who was researching the lives of the seven Kenney sisters as part of her DPhil research in Oxford’s Faculty of History.

Annie Kenney went on to become one of the most prominent leaders of the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU). After Christabel Pankhurst fled to Paris in 1912, Kenney led the organisation through its most difficult and dangerous years. She served several prison sentences, went on hunger strikes that devastated her health, and eventually spent a year on the run from the authorities as a ‘Mouse’ released under the notorious ‘Cat and Mouse Act’. She was not active in politics after the vote was won for some women in 1918, but remained loyal to the Pankhursts and the WSPU for the rest of her life.

Dr Jenkins said: ‘Annie Kenney was one of the leading suffragettes, but, like other working-class women who played a central part in the fight for the vote, her story and significance is often underestimated and poorly understood. This letter provides new insight into Annie’s private thoughts and feelings at this turning point in the campaign for the vote, as well as showing the warm reception she received from the local community and other activists. This is an exciting and revealing document which deepens our understanding of the battle for suffrage and the women who fought it.’

Annie’s letter shows the close and loving relationship among the Kenney family, whose background was in the mills of Oldham in Greater Manchester, and several of whom went on to have important careers in political, professional and public life. The youngest sister, Jessie, was another leading suffragette who also gained notoriety for her acts of daring: dressing as a telegraph boy to attempt to heckle then Chancellor David Lloyd George and as part of a trio who attacked Prime Minister Herbert Asquith on his holiday.

Nell Kenney, who received the letter, organised a mass protest in Nottingham that narrowly escaped becoming a riot. Two other sisters, Jane and Caroline, also supported the suffragettes’ work, but dedicated their lives to becoming some of the first Montessori teachers in the world, studying with Dr Maria Montessori herself and joining forces with Alexander Graham Bell to pioneer Montessori education in the United States. Meanwhile, their brother Rowland was a leading socialist and the first editor of the Daily Herald, before becoming a pioneer of political propaganda in the First World War.

Author Helen Pankhurst, granddaughter of Sylvia Pankhurst and a leading campaigner for women’s rights, said: ‘One hundred years on from the first women winning the vote, we are still learning more about the remarkable women who led the campaign for us all to have that right. As this important and very personal letter from one sister to another shows, the campaign for suffrage involved high risks and huge personal costs – especially in these early stages when the cause was unpopular and the outcome uncertain. As we mark the centenary of their success, it is right that we remember their sacrifices and remind ourselves that women in the UK and around the world are still taking those risks to achieve true equality for all.’

The letter is on display at Gallery Oldham from 29 September to 12 January as part of the Peace and Plenty? Oldham and the First World War exhibition. It is on loan from the British Columbia Archives in Victoria, Canada.

Oldham Councillor Hannah Roberts, Elected Member Champion for the Suffrage to Citizenship Programme, said: ‘I am delighted that this letter has come to light, and how great that we get to see it being exhibited in the birthplace of Annie Kenney herself. We are very lucky to have it on loan from Canada. It will make a lovely addition to the suffrage artefacts already held by Gallery Oldham, and I hope people will go along to see this significant piece of Oldham’s suffrage history.’

Professor Jack Lohman, Chief Executive of the Royal British Columbia Museum and Archives, added: ‘We are so pleased to be able to share this poignant letter with Gallery Oldham and its visitors, and to add something so personal to the important story of the suffrage movement. The British Columbia Archives hold thousands of stories that connect us around the world, and Annie Kenney’s letter is an outstanding example of our shared histories.’

Annie’s letter

62 Nelson Street,

Manchester

Oct 17.05

My Dear Nellie

You may be surprised when I tell you I was released from Strangeways yesterday morning. There were over one hundred people waiting. I had a lovely boquet (sic) of flowers sent me from the Oldham Socialists. Miss Pankhurst is still there untill (sic) Friday. Manchester is alive I can assure you Last night a protest meeting was held for me in Stevenson Square over 2000 people were there Lenard (sic) Hall came to speak on our behalf the only thing I am sorry about is those at home and Kitty and Jennie and You, I cannot tell you how pleased I was to receive your letter and to find you so kind about it, I thought you would have been so indignant with me I cannot tell you anything here as there is so much to tell. I am staying at Pankhurst (sic) for an indefinite time of course I am able to send money home every week. I sent it last week so that is alright. Alice is awfully angry about it but I don’t blame her, I’m living in hope to repay her for it all. She is working for me yet, they are removing to morrow. I can’t be there but Jessie is away from work for a day or so. I will come and spend a weekend with you as soon as possible. I expect being at Middlesbourgh (sic) for a week or so, and I will write you from there,

Ever Your Loving Sis

Nan.