Let the people speak: British history with voices

Dr Philip Carter is an Oxford historian and Senior Research and Publication Editor of the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (ODNB). In a guest post for Arts Blog, he explains a new development in the Oxford DNB: the addition of voice recordings of historical individuals to their biographies.

'For 135 years Oxford’s Dictionary of National Biography has been the national record of noteworthy men and women who’ve shaped the British past. Today’s Dictionary retains many attributes of its Victorian forebear, not least a focus on concise and balanced accounts of individuals from all walks of national history. But there have also been changes in how these life stories are told.

In its Victorian incarnation the Dictionary presented each life as a double-column printed text. Publication of the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography online, in 2004, saw the addition of portrait images.

Today the Dictionary includes portraits of 11,500 of its 60,000 subjects. Every image is a depiction of the sitter from life, so as to convey an aspect of his or her personality.

Now the Oxford DNB takes the next step - the inclusion of sound - with a project to link biographies to voice recordings made by an initial selection of 750 historical individuals. In doing so, we’ve teamed up with the British Library whose ‘Early Spoken Word’ archive is a trove of documentary clips, oral histories, and music recordings—allowing us to hear historical figures orate, converse, and perform.

Partnerships like this are the way forward for digital reference works. They create interconnections of specialist collections, be they biographies, sound recordings, art works or archive film footage.

'ODNB’s sounds project is the first in a series of collaborations that will see the Dictionary integrated with digitized manuscripts, creative works, television clips, memorials, Blue Plaques, and further voice recordings. In doing so, it draws on content provided by, among others, Art UK, the BBC, English Heritage, the Royal Collection, and Westminster Abbey.

For researchers it’s an opportunity to follow a biography from the traditional written text to more intimate instances and expressions of a life: handwriting and marginalia, movements caught on camera, houses lived in and streets once walked, and of course voices.

It’s the ability to hear historical figures speak—to catch their accents and their intonations— that’s the principal attraction of linking ODNB biographies to sound recordings. Hearing the voice reminds us that a distant historical figure was a living person as well as the subject of a modern biographical text.

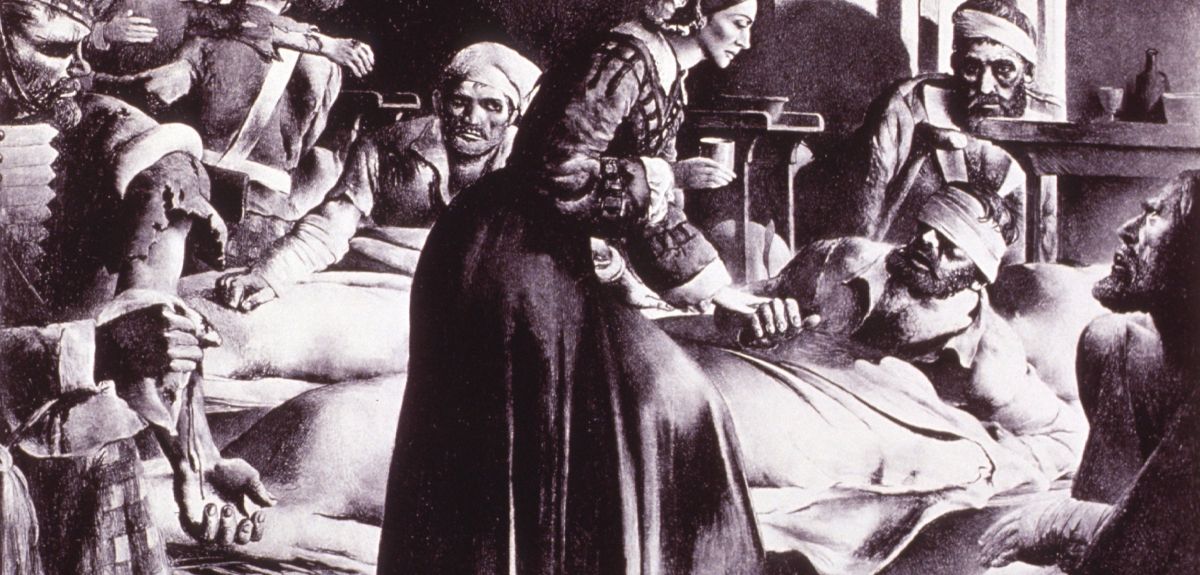

The effect is particularly striking in the Oxford DNB’s earliest link to the British Library archive—that for Florence Nightingale who spoke in support of the Light Brigade Relief Fund in July 1890. Barely audible over the hiss, she concludes her short, carefully enunciated message:

‘When I am no longer even a memory, just a name, I hope my voice may perpetuate the great work of my life. God bless my dear old comrades of Balaclava and bring them safe to shore. Florence Nightingale’.'

The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography is a research and publishing project of Oxford’s History Faculty and Oxford University Press.