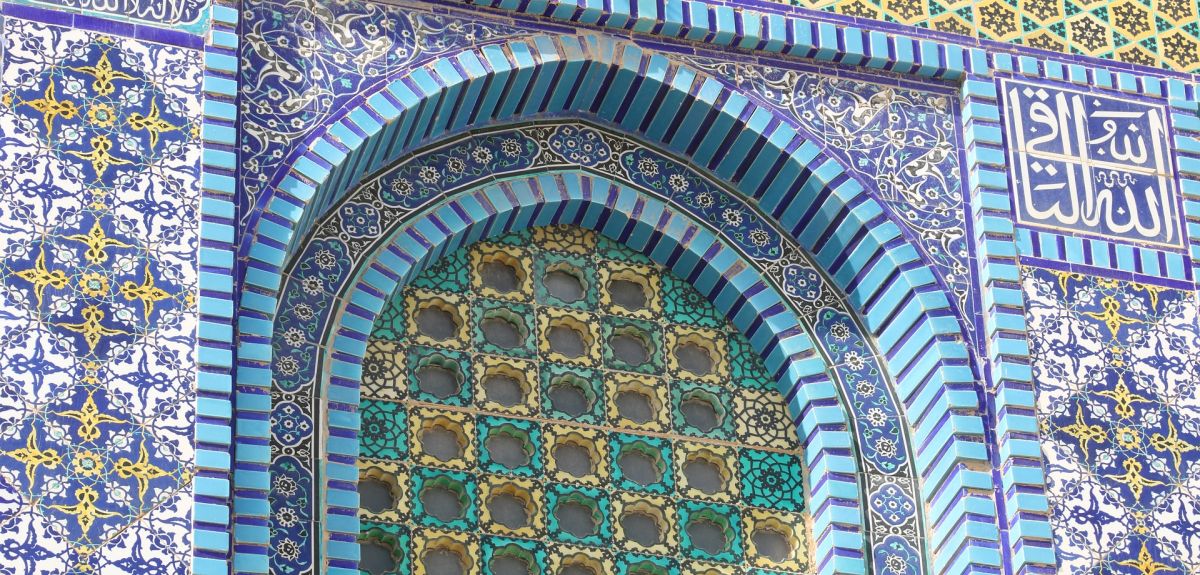

Image credit: Pixabay

How did the Christian Middle East become predominantly Muslim?

How did the ancient Middle East transform from a majority-Christian world to the majority-Muslim world we know today, and what role did violence play in this process? These questions lie at the heart of Christian Martyrs under Islam: Religious Violence and the Making of the Muslim World (Princeton University Press), a new book by associate professor of Islamic history Christian C. Sahner. In a guest post for Arts Blog, Professor Sahner, from Oxford's Faculty of Oriental Studies, explores his findings.

Although Arab armies quickly established an Islamic empire during the seventh and eighth centuries, it took far longer for an Islamic society to emerge within its frontiers. Indeed, despite widespread images of “conversion by the sword” in popular culture, the process of Islamisation in the early period was slow, complex, and often non-violent. Forced conversion was fairly uncommon, and religious change was driven far more by factors such as intermarriage, economic self-interest, and political allegiance. Non-Muslims were generally entitled to continue practising their faiths, provided they abided by the laws of their rulers and paid special taxes. Muslim elites sometimes even discouraged conversion, for when non-Muslims embraced Islam, they no longer had to provide these taxes to the state, and thus the state’s fiscal base threatened to contract. Compounding this was a belief among some that Islam was a special dispensation only for the Arab people. Thus, when non-Arabs converted, they were sometimes treated as second-class citizens, despised as little better than Christians, Jews, or other “infidels”.

This combination of factors meant that the Middle East became predominantly Muslim far later than an older generation of scholars once assumed. Although we lack reliable demographic data from the pre-modern period with which we could make precise estimates (such as censuses or tax registers), historians surmise that Syria-Palestine crossed the threshold of a Muslim demographic majority in the 12th century, while Egypt may have passed this benchmark even later, possibly in the 14th. What we mean by the “Islamic world” thus takes on new meaning: Muslims were the undisputed rulers of the Middle East from the seventh century onward, but they presided over a mixed society in which they were often dramatically outnumbered by non-Muslims.

It is against this backdrop that the phenomenon of Christian martyrdom took place. We know about these martyrs thanks to a large but understudied corpus of hagiographical texts written in a variety of medieval languages, including Greek, Arabic, Latin, Syriac, Armenian, and Georgian. Set in places as varied as Córdoba, the Nile Delta, Jerusalem, and the South Caucasus, they tell the lives of Christians who ran afoul of the Muslim authorities, were executed, and were later revered as saints. The martyrs were participants in this broader culture of conversion, but as their deaths make clear, they were also dissenters from this culture, individuals who protested Islamisation and attempted to reverse the tide of religious change.

The first and largest group consisted of Christians who converted to Islam but reneged and returned to Christianity. Because apostasy came to be considered a capital offence under Islamic law, they faced execution if found guilty. The second group was made up of Muslim converts to Christianity who had no prior experience of their new religion. The third consisted of Christians who were executed for blasphemy; that is, publicly reviling the Prophet Muhammad, usually before a high-ranking Muslim official. The martyrs were small in number – not more than around 270 discrete individuals between Spain and Iraq – a testament to the relative absence of systematic persecution at the time.

As a collection of texts, the lives of the martyrs represent one of the richest bodies of evidence for understanding conversion in the early medieval Middle East. Yet these sources must be treated with great caution. Saints’ lives are a notoriously formulaic genre, filled with reports of miracles, literary motifs, and theological polemics which can make it difficult to know what “really happened”. Reading the sources alongside contemporary Islamic texts, the book argues that many biographies have a strong basis in reality. At the same time, they were shaped by the literary, social and spiritual priorities of their authors, who were determined to create models of resistance for their flocks, who were increasingly tempted by the faith and culture of the conquerors.

Christian Martyrs under Islam describes a lost world in which Muslims and Christians rubbed shoulders in the most intimate of settings, from workshops and markets to city blocks and even marital beds. Not surprisingly, these interactions gave rise to overlapping practices, including behaviours that blurred the line between the Islam and Christianity. To ensure that conversion and assimilation went exclusively in the direction of Islam, Muslim officials executed the most flagrant boundary-crossers, and Christians, in turn, revered some of these people as saints.