Early life hunt inspired by oldest fossils debate

The resolution of a decades-old debate about the oldest fossils on Earth can reinvigorate the search for early life and open up a window on the strange world of ancient microorganisms.

A team from Oxford University, the University of Bristol, and the University of Western Australia has analysed 3.46 billion-year-old rocks containing structures once thought to be Earth’s oldest microfossils. The team present high-spatial resolution data that show these 'Apex chert microfossils' do not match younger fossils of microscopic life and instead comprise peculiarly-shaped minerals.

Yet, as the team report this week in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, resolving this controversy has inspired new approaches to the study of microfossils that are revolutionising how we think about the early fossil record.

The publication embodies one of the key achievements of study author and recent Lyell medallist Professor Martin Brasier of Oxford University's Department of Earth Sciences, who died in December 2014, and was a driving force behind an evidence-based revaluation of early life.

After their discovery in 1993 the 'Apex chert microfossils' (0.5-20 micrometres wide) in rocks from Pilbara, Western Australia, were heralded as the earliest evidence for life on Earth. Despite early questions about their colour and complexity they were even used to validate 'microfossils' in the Martian meteorite ALH 84001. In 2002 a team led by Professor Brasier revealed that these chert rocks hosted high-temperature hydrothermal activity and proposed that the structures identified as microfossils were in fact pseudofossils formed by the redistribution of carbon around mineral grains during hydrothermal events.

The 'Apex chert microfossils' debate has remained hard to resolve because scientific instrumentation has only recently reached the level of resolution needed to map both the chemical composition and morphology of these 'microfossils' at the sub-micrometre scale.

Now a team led by Oxford and Bristol scientists has come up with new high-spatial resolution data that clearly demonstrate that the 'Apex chert microfossils' comprise stacks of plate-like clay minerals arranged into branched and tapered worm-like chains. Carbon was then absorbed onto the edges of these minerals during the circulation of hydrothermal fluids, giving a false impression of carbon-rich cell-like walls.

Dr David Wacey, a Marie Curie Fellow in Bristol's School of Earth Sciences and co-author of the report, said: 'It soon became clear that the distribution of carbon was unlike anything seen in authentic microfossils. A false appearance of cellular compartments is given by multiple plates of clay minerals having a chemistry entirely compatible with a high temperature hydrothermal setting. We studied a range of authentic microfossils using the same transmission electron microscopy technique and in all cases these reveal coherent, rounded envelopes of carbon having dimensions consistent with their origin from cell walls and sheaths. At high spatial resolution, the Apex ‘microfossils’ lack all evidence for coherent, rounded walls. Instead, they have a complex, incoherent spiky morphology, evidently formed by filaments of clay crystals coated with iron and carbon.'

Before his death Professor Brasier of Oxford University's Department of Earth Sciences commented: 'This research should, at long last, provide a closing chapter for the 'Apex microfossil' debate. Such discussions have encouraged us to refine both the questions and techniques needed to search for life remote in time and space, including signals from Mars or beyond. It is hoped that textbooks and websites will now focus upon recent and more robust discoveries of microfossils of a similar age from Western Australia, also examined by us in the same article.'

It is microfossils from other rocks, also analysed in the new study, that are giving tantalising insights into the diversity and strangeness of microorganisms captured in the early fossil record. In particular fossils in the 1.88 billion-year-old Gunflint Chert from Northwestern Ontario, Canada, fascinated study author Dr Jonathan Antcliffe of Oxford University's Department of Zoology.

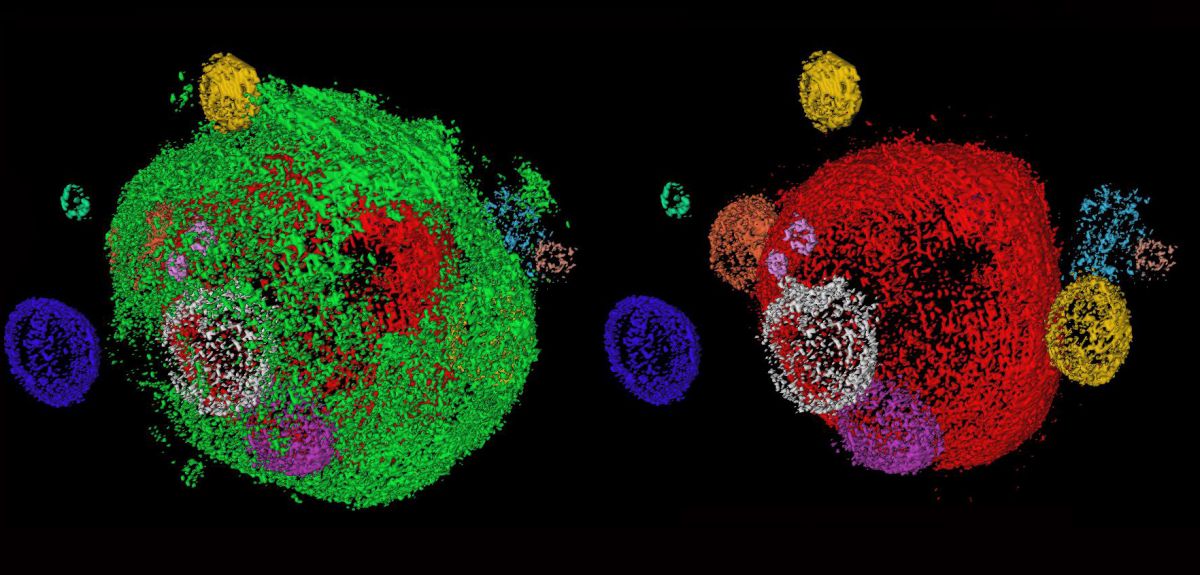

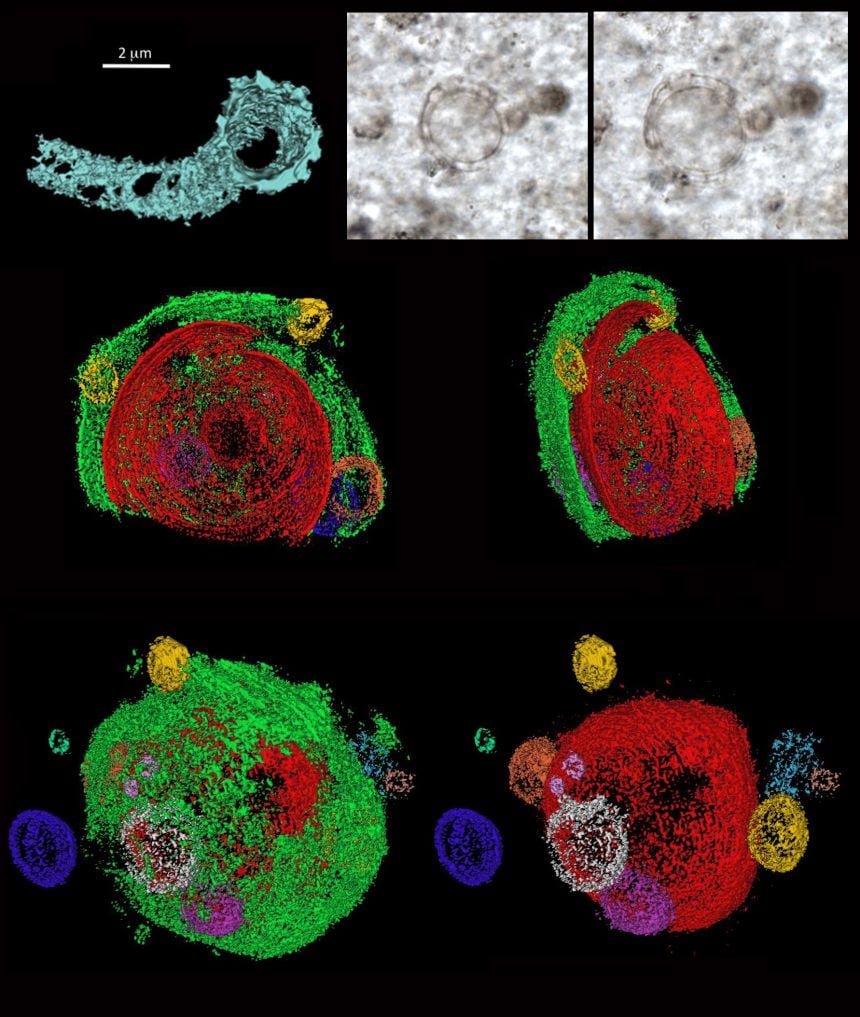

Dr Antcliffe said: 'One of the most incredible fossils is a microbe called Eosphaera which is a strange array of spheroids and tubercles in between the layers of a complex dual sheath. 3D nanoscale reconstructions of this most ancient complex bacterial fossil reveals features so far unmatched in any modern microbe. Eosphaera shows that the fossil record is now revealing new biological forms even at the cellular level.'

Eosphaera is probably so strange because the Proterozoic ocean it inhabited was very different from today’s oceans. The Gunflint Chert fossils preserve life at a time when complex cells were just starting to emerge, with Eosphaera showing us that these first tentative steps might take forms we could not predict from looking at modern microbes.

Dr Antcliffe added: ‘It is likely that Eosphaera is somehow related to modern cyanobacteria but at a time before even eukaryotic algae evolved then the constraints upon bacterial form and function would have been quite different. There would have been no competition between bacteria and algae, so bacteria were freer to explore different morphologies that would later come to be occupied by organisms with more complex eukaryotic cells. Life was experimenting for the very first time with how to get large and the fossil record tells us it was doing this in a quite unique way.'

Gunflint Chert microfossil of microbe Eosphaera with 3D reconstruction

Gunflint Chert microfossil of microbe Eosphaera with 3D reconstructionA report of the research, entitled ‘Changing the picture of Earth's earliest fossils (3.5-1.9 Ga) with new approaches and new discoveries’, is published in PNAS.

Statins do not cause the majority of side effects listed in package leaflets

Statins do not cause the majority of side effects listed in package leaflets

Activism proves a stimulating topic at Sheldonian Series event

Activism proves a stimulating topic at Sheldonian Series event

New Oxford-led initiative launches to train future leaders in transformative technologies for pharmaceutical research

New Oxford-led initiative launches to train future leaders in transformative technologies for pharmaceutical research