Myths, mistakes and Kremlin revenge: Dr Vlad Mykhnenko and the devastating invasion of his Ukraine home

‘We do not know if they are alive,’ Dr Vlad Mykhnenko says with hesitant frankness of his mother’s cousins in Mariupol. The port city in eastern Ukraine has been a refuge for thousands of Donbas residents, when their previous homes in Donetsk and further east, were taken over by the Russians in 2014. Now, says the Oxford academic, they have had no word from their five relatives in Mariupol since ‘day four’ of the current invasion.

Like so many other Ukrainians in the west, Dr Mykhnenko, an expert in post-communist transformation of Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union, urban and regional economic development, and a fellow of St Peter’s college Oxford, has spent many desperate hours while the Russian army over-runs his country.

Most of his family was there, some three weeks ago, when the tanks arrived. On ‘day one’, his parents had left Kyiv for a remote rural location some 25km south, near Vasylkiv. They hoped the countryside would provide a safe refuge. But, on day two, came the airborne arrival of Putin’s troops. The locals hunted down Russian paratroopers in the fields around the house. And Dr Mykhnenko urged his parents to leave the country. Along with millions of Ukrainians since, they took what they could, and left Ukraine.

‘The Russian IL-76 military airlifter was shot down, as it approached Vasylkiv airfield, but some soldiers escaped before the crash, landing by parachute,’ says Dr Mykhnenko, clearly still stunned by what had happened near his parent’s country hideaway. ‘Local villagers, farmers, came and told my parents to stay indoors and take cover, then they hunted the paratroopers down in the fields, shooting five of them.’

The Russian IL-76 military airlifter was shot down...but some soldiers escaped before the crash, landing by parachute...Local villagers, farmers, came and told my parents to stay indoors and take cover, then they hunted the paratroopers down in the fields, shooting five of them

Dr Vlad Mykhnenko

This was far too close to comfort and, fearful for their safety, Dr Mykhnenko says, ‘We put pressure on my parents to go.’

But it was not going to be easy. Where would they go? How would they get there safely?

There was family in Lithuania, they could go there. But that was a long journey – and many of the roads were unsafe, either bombed or infiltrated by Russian recce or scouting units, engaged in sabotage. With no choice, though, Dr Mykhnenko says, they set off on what was to be a 1,000 mile journey to safety using small back roads, stopping at every petrol station en route, because rationing meant they could never have more than 10 litres of fuel.

‘It took six days to get to Lithuania,’ he says. ‘It was a massive relief when they arrived.’

They are now temporarily safe in Vilnius, along with Dr Mykhnenko’s brother and his three young children. His sister-in-law, who is in the military, is still in Ukraine. He says grimly, ‘My brother would change places with her, probably fearing to be alone with the little ones more than a Russian tank, but she is more useful to the military.’

Dr Mykhnenko is urgently trying to bring them to the UK to be with him. A neighbour has offered rooms to his brother. Everyone at the university, and his college, St Peter’s, and in his neighbourhood has been very kind and supportive, he says. But the visa office in Lithuania is only open on two mornings a month, Dr Mykhnenko says, incredulous.

At least they are safe, he says. But this is not the first time the family has had to move. In less than 100 years, the family has had to travel long distances to safety on at least four occasions. During Stalin’s terror-famine – known in Ukraine as the Holodomor – his father’s family left the agricultural centre of Ukraine near Novomyrhorod to live in the industrial region of the Donbas. It was better than the other option, he says, ‘It meant they escaped Siberia. They did not starve to death. So they lived in Donetsk, built a house in an informal slum, and kept a very low profile.’

Newly-built detached houses for the post-communist nouveau riche, former Kalinin Coal Mine Settlement, Donetsk, September 2009

Newly-built detached houses for the post-communist nouveau riche, former Kalinin Coal Mine Settlement, Donetsk, September 2009His mother’s family, meanwhile, were of Zaporozhian Cossack heritage [Cossacks were high on the list of people Stalin hated] and they too migrated to Donetsk, rather than something worse. No one wanted to live there, if they had any other option. No one wanted to work in the coal mines, he says, unless they had to – and his father had to. There was no choice.

Vlad Mykhnenko (aged 8), with his brother, maternal grandmother, mother, and first cousin, Donetsk, summer 1983.

Vlad Mykhnenko (aged 8), with his brother, maternal grandmother, mother, and first cousin, Donetsk, summer 1983.

‘They were very tough conditions...one miner was killed for every million tonnes of coal,’ he says. ‘Fairly often, you would hear the cries of women, young women in their 20s and 30s, burying their husbands, lamenting their deaths.’

Dr Mykhnenko says the history of the region is best depicted in a book by the US-based academic, Hiroaki Kuromiya, Freedom and Terror in the Donbas: A Ukrainian-Russian Borderland, 1870s-1990s. The Donetsk area was described as like the Wild West on the fringe of Ukraine, he says, ‘People went there seeking freedom, they were running from persecution.’

His father was badly injured – and so was able to leave the mines. He became a communist city-level apparatchik, according to Dr Mykhnenko, ‘It was purely pragmatic, the way to upward social mobility in the Soviet Union, the only way to make a career.’

His father eventually became an academic, Professor of Public Policy. And the Mykhnenko family had moved to Kyiv in 2002, long before that first Putin war in 2014. They were escaping from the appalling corruption which engulfed the area, after the collapse of the Soviet Union, during Ukraine’s early years of independence.

‘They left before my father got into trouble,’ he says matter-of-factly. ‘They went to a tiny flat in central Kyiv.’

Since 2014, Donetsk has been a byword for Russian ambition and invasion, says Dr Mykhnenko, as the local area was effectively annexed by the ‘Russian separatists’ who were, it was claimed, desperate to leave Ukraine. But Dr Mykhnenko’s aunt and cousins remained there and were still there at the time of the spring 2014 invasion. They lost touch after the occupation, he says, with evident sadness.

As though things could not get worse - his mother’s cousins [are] in Mariupol, about an hour drive south of Donetsk. No one had heard of the place before, but now everyone has. Mariupol has been laid waste by Russian forces

As though things could not get worse - his mother’s cousins grew up by the sea, in Mariupol, about an hour drive south of Donetsk. No one had heard of the place before, but now everyone has. Mariupol has been laid waste by Russian forces – leading to international condemnation of atrocities and concerns about the conditions in the besieged city, which are said to be medieval.

‘My mother has not heard anything since day four of the invasion,’ he says, fearful of what may have happened. ‘We don’t know if they’re alive. On day four, they had electricity.’

Before the Russian ‘operations’, no one in the west had heard of Donetsk, let alone Mariupol, aside from football fans, Dr Mykhnenko says with grim humour. Shakhtar Donetsk was first displaced to Lviv, then to Kharkiv, and is now entirely homeless. It was one of the top teams in Ukraine and a mid-ranking football club in the Soviet Union, beforehand. And the city was one of the centres for the European Championship, which were held jointly in Ukraine and Poland in 2012.

‘I would often meet football fans on a plane, flying somewhere, who said they had been there, in Donetsk,’ he smiles, as if recalling someone else’s life.

Having grown up under Soviet domination and communism, the teenaged Dr Mykhnenko was passionately pro-independence for Ukraine, agitating for the collapse of the Soviet empire in 1989-1991. It led him to undertake research into his country and the post-Communist transition era – which are still very misunderstood, he says, and myths and misconceptions have been allowed to flourish.

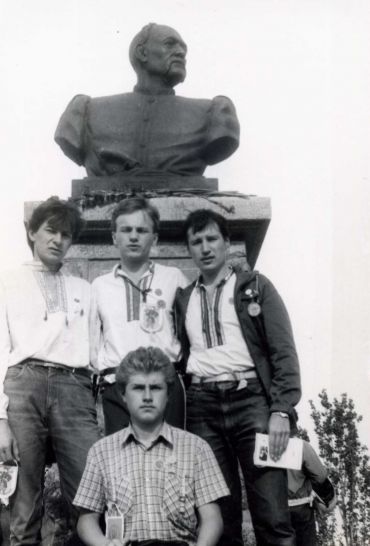

Members of Ukrainian Historical and Ethnographic Club Donets Kurin (Ye. Pokrov, D. Bilyi, A. Kornev, V. Mykhnenko, aged 15, V. Zadunaiskyi, I. Derkach), celebrating 500th Anniversary of Zaporozhian Cossacks, Chortomlyk Host, village of Kapulivka, Nikopol District, Dnipro oblast, 5 August 1990.

Members of Ukrainian Historical and Ethnographic Club Donets Kurin (Ye. Pokrov, D. Bilyi, A. Kornev, V. Mykhnenko, aged 15, V. Zadunaiskyi, I. Derkach), celebrating 500th Anniversary of Zaporozhian Cossacks, Chortomlyk Host, village of Kapulivka, Nikopol District, Dnipro oblast, 5 August 1990.  Members of Ukrainian Historical and Ethnographic Club

Members of Ukrainian Historical and Ethnographic Club Dr Mykhnenko insists, for instance, there is very little distinction between local Russian and Ukrainian-speaking people these days and it is quite wrong to characterise the current invasion as having anything to do with protecting ‘ethnic Russians’, ‘It is a bilingual country...a civic identity has emerged...the local mayors who have been captured or kidnapped by the Russians, they have Russian surnames: Ivan Fedorov, Yevgeniy Matveyev.’

He adds, ‘There has been a myth about this colossal, deep East/West Ukraine divide but over the last 15-20 years, people from different backgrounds had amalgamated.’

So what can Putin possibly hope to get out of this? Even if the people in the east had been pro-Russian [which they aren’t, insists Dr Mykhnenko], they surely would not support Russia any more.

Dr Mykhnenko explains, ‘Putin is not mad, but this [the siege of Ukrainian cities] shows he is in a mad rage because he is not getting what he wants....it’s like a tantrum...but even if he takes over Mariupol, there will be a mad outcome [nothing will be left].’

‘It will take decades to rebuild...$300 billion of Russian sovereign wealth frozen in Western banks could be given to Ukraine as reparations.’

Despite everything, the academic is hopeful, ‘If Ukraine manages to hold on for another two weeks, Russia will collapse [because of the sanctions]. They – ‘the second largest army in the world’ – have had to request food rations from the Chinese...imagine how humiliating that was.’

Will Putin be forced out? Perhaps, he says, adding, ‘Russian generals will probably take him out rather than take the blame...they will be scapegoated, otherwise, accused of treason.’

Will Putin be forced out? Perhaps, he says, adding, ‘Russian generals will probably take him out rather than take the blame...they will be scapegoated, otherwise, accused of treason.’

He points out that, for 20 years, the Russian state has spent billions creating a myth of greater Russia – so it would be very hard, at first, for public opinion in the country to comprehend what is happening – a humiliating military defeat – from a different perspective.

‘Word will spread, though,’ he says. ‘People know burials are taking place. It affects morale...people there are really struggling. They may love Putin, but they love their sons more.’

He adds with incredulity, ‘They sent a military orchestra to fight in Kharkiv!’

Misconceptions, he says, have affected the external view of the post-Soviet east, ‘There was an economic crisis [after independence]. Ukraine lost 60% of its GDP – making it twice as big as the Great Depression of the 1930s.’

But the west was not attuned to the problems and western scholars, he says, were imposing post-colonial theories on the newly democratic east, borrowed from western experience, ‘They didn’t look at it correctly. They didn’t understand. Some were brilliant, but there was a lot of patronising rubbish. I wanted to give voice to the opinions of Ukrainians, of east Europeans.’

I think the key problem was with superimposing, if not copy-pasting, the economic market reform plans which were previously implemented in the Latin American context. The Global East, so to speak, was different. Transforming its centrally planned economies and totalitarian societies was a task requiring intensive care

Dr Mykhnenko

Dr Mykhnenko explains, ‘I think the key problem was with superimposing, if not copy-pasting, the economic market reform plans which were previously implemented in the Latin American context. The East, so to speak, was different. Transforming its centrally planned economies and totalitarian societies was a task requiring intensive care. To some extent, the failure of Russian post-communist transition, our collective failure to help transform the Russian society, to prevent the former Communist elites - the KGB, for god’s sake! - from grabbing power, is all part of that monumental transition failure.

‘The Russian rulers, the Kremlin, are now engaged in a bloody “grudge match” against the West. They are trying to take revenge in Ukraine for their defeat suffered in the Cold War. Whatever the cost, we must not allow that to happen.’

After his first degrees in Kyiv, Vlad went to Budapest to study International Relations and European Studies, having won a highly competitive Soros Foundations scholarship to Central European University. He went from there to Cambridge to undertake research for a doctorate into the political economy of post-communist transition in two largest old industrial regions in Europe – the Ukrainian Donbas and Poland’s Upper Silesia (full text is available here). Yet by the time he finished, the appetite and interest in the post-communist world had waned. It was ‘the end of history’, after all.

‘Nobody wanted to hear about post-Communism,’ he says.

The Russian rulers, the Kremlin, are now engaged in a bloody “grudge match” against the West. They are trying to take revenge in Ukraine for their defeat suffered in the Cold War. Whatever the cost, we must not allow that to happen

Dr Mykhnenko

This has led the academic in a very different direction – researching and investigating post-industrial urban landscapes. For much of the last decade, he has been devoted to research into declining or ‘shrinking’ cities, such as his ‘hometown’ Donetsk.

‘Forty-two per cent of cities across Europe are shrinking, not growing,’ he maintains. ‘I have just finished 43 months of work looking at fostering resilient cities in these places, producing analysis which will be applicable and policy relevant.’

There are five reasons cities shrink, he says:

- Economic decline, e.g., de-industrialisation;

- Demographic decline due to low fertility;

- Suburbanisation or escape to the suburbs;

- Politics and war;

- Natural disaster.

The first three are caused by long term chronic stress, he explains, the final two by sudden shock. He very much hopes his work will be of help in rebuilding Ukrainian cities after current devastation.

See Dr Mykhnenko's Expert Comment about Putin's war Expert Comment: Putin’s war - How did we get here? ....Ukraine 2014 | University of Oxford.

By Sarah Whitebloom