Renaissance 'father of modern publishing’ is celebrated in Oxford historian’s exhibition

Can an idea be owned, bought and sold? We think of intellectual property as a modern concept, but a new exhibition curated by an Oxford historian reveals that copyright disputes and the problem of piracy were in play at least five centuries ago.

Aldus Manutius: The Struggle and the Dream is a new display at the Bodleian Library chronicling the work of Aldus Manutius (c.1450-1515), an Italian humanist who has become known as the "father of modern publishing", and marking the fifth centenary of his death.

Dr Oren Margolis, a historian of the Italian Renaissance who curated the exhibition, explained what made Aldus the first of his kind. 'Most printers who came before him had technical backgrounds: Gutenberg was a goldsmith, for instance,' he said. 'Aldus was a humanist scholar who came to printing very deliberately as an extension of his humanist enterprise.'

'We shouldn't imagine him operating the press or cutting the type himself, though by all accounts he was deeply involved with every aspect of the printing process - always reading and checking - and his handwriting was apparently quite influential in the development of the typefaces. Aldus had an overview of the whole operation and a definite idea of his purpose as a publisher.

'Almost every book he published opens with a letter "from Aldus to the scholars". We shouldn't imagine Aldus was interested in popularising classical literature. Like many Renaissance humanists, he was culturally elitist. But he was very interested in accessibility.'

Aldus pioneered the octavo format: small, portable books, which could be carried and read like the paperbacks of today. They were cheaper and easier to handle than the large books which preceded them, and were produced in print runs of thousands.

'This isn’t just about bibliophilia. If Aldus were around today, he wouldn't be producing anything like this,' said Dr Margolis. 'He was publishing to extend his own agenda, and he wanted to make these works as widely accessible as possible. He would be more like Amazon, an innovator in media, selling en masse.'

The exhibition features several books produced by the Aldine Press as showpieces to put these innovations on display: text is artfully arranged on the page, forming symmetrical "goblets", and Latin, Greek and Hebrew text appear side by side. Aldus was also responsible for the first use of italic type.

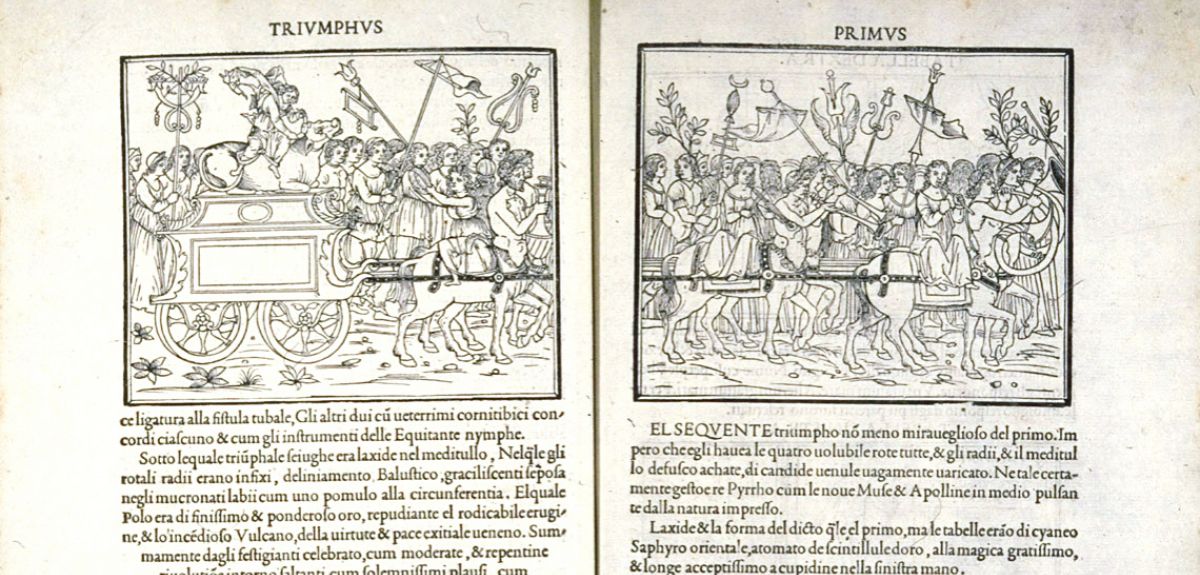

To raise money for a definitive edition of Aristotle's works, the press published a variety of smaller works, including its first-ever publication, a textbook of Greek grammar. 'If you wanted to make money, you published a grammar,' said Dr Margolis. This book is on display in the exhibition, alongside more unusual texts, such as the Hypnerotomachia Poliphili (pictured), an illustrated dream-vision in which the hero explores a series of surreal gardens and monuments in search of his love.

Aldus was forced to develop other innovations in response to the problem of piracy. 'For the first time, intellectual property becomes an issue, because you're producing something that isn't unique any more,' sid Dr Margolis. 'It's the same problem for publishers that we see now: if technology makes it easy to copy something, it's easy for counterfeiters to produce their own copies.'

Aldus acquired a legal monopoly on the use of the typeface in which the octavo editions were set. However, since the type itself was the work of his punchcutter, Francesco Griffo, the two argued over who had the right to claim ownership of the work, and were never reconciled.

These legal privileges meant Aldus could protect the work to an extent in Italy, but elsewhere things were more complicated. 'There was a large printing industry in Lyon,' said Dr Margolis. 'But it was a bit more of a 'Wild West' in terms of piracy and counterfeiting. The Aldine Press works were popular, so it was worth the counterfeiters' while to produce pirate editions.

'It got to the point that Aldus wrote a warning, advising people about these fake editions, and pointing out the various ways in which they differed from the real thing. Of course, in some ways this was a mistake as the pirates now had a perfect cheat-sheet to work from.'

Aldus was worried about piracy not only as a financial risk, but also out of concern that flawed copies would corrupt the texts which he strove to make accurate. To mark the works of the press as his own, Aldus developed his printer's device - a dolphin entwining an anchor - from an image found on a Roman coin, which he associated with the motto festina lente, "make haste slowly".

The exhibition will also feature a one-day display, curated by three student curatorial assistants: Jennifer Allan, Anna Clark and Qaleeda Talib, who have also produced additional material for the online exhibition. 'We have some of the best research libraries and collections in the world here in Oxford,' said Dr Margolis. 'New College, for instance, owns the only complete copy of the Aldine Aristotle printed on vellum. It's one of the world's rarest Aldine items. It's unusual for students elsewhere to have the opportunity to work with books like this in person, so it's important that we encourage teaching and research in these collections.'

Aldus Manutius: The Struggle and the Dream is open until the 22nd of February in the Proscholium at the Bodleian Library. The student curators' one-day display is on the 6th of February.

Expert Comment: The Pentagon-Anthropic dispute reflects governance failures - with consequences that extend well beyond Washington

Expert Comment: The Pentagon-Anthropic dispute reflects governance failures - with consequences that extend well beyond Washington

Schwarzman Centre to open doors to public with major celebration

Schwarzman Centre to open doors to public with major celebration

Stroke Cognition Calculator could help predict thinking problems after stroke

Stroke Cognition Calculator could help predict thinking problems after stroke

Digital tool that personalises antidepressant treatment significantly improves outcomes of people with depression

Digital tool that personalises antidepressant treatment significantly improves outcomes of people with depression

British children are growing taller but not for the right reasons

British children are growing taller but not for the right reasons