Exceptional people make a difference: Sudhir Hazareesingh on heroes...and villains

A lifetime ago (or a little over 18 months), a landmark event was delayed by the pandemic. It was far from the worst thing that happened in 2020, but unlike the Bond film, it was merely pushed back six months to autumn. But when Black Spartacus was finally published in September last year, it captured an international wave of anger and concern over slavery, colonialism and racial inequity. And its author, Balliol Politics Fellow Sudhir Hazareesingh received global acclaim for his incisive biography of the 18th century Haitian leader, Toussaint Louverture, who led a slaves’ revolt – and battled against three empires, before being tricked into captivity.

The book won the 2021 Wolfson History Prize, Britain’s most prestigious history accolade, awarded to a work which combines research excellence with accessibility to a lay audience.

Talking in his Oxford study, which he is visiting for the first time since March 2020, Sudhir speaks vividly about the ‘hero’ of his book, the brilliant and extraordinary Toussaint Louverture, who came to lead a remarkable revolution in the former French colony of Saint-Domingue, confounding stereotypes about the inferiority of enslaved people and embracing the progressive ideas about equality and fraternity coming out of Europe. It is a tale of epic battles, creative ideas and Machiavellian ingenuity and a very rare successful revolt against slavery. It led to the founding of Haiti, in 1804, the world’s first free post-colonial Caribbean state – years before the English banned the slave trade and decades before slaves were freed in the US.

Sudhir speaks vividly about the ‘hero’ of his book, the brilliant and extraordinary Toussaint Louverture, who came to lead a remarkable revolution in the former French colony of Saint-Domingue...It is a tale of epic battles, creative ideas and Machiavellian ingenuity and a very rare successful revolt against slavery

As a book about the devastating impact of colonialism, Black Spartacus could have been written specifically for 2020, but it was the delayed result of years of painstaking research and follows Sudhir’s biographies of other French figures, including Napoleon and de Gaulle.

Sudhir notes he embarked on the study of the Haitian revolutionary partly because there was so much material on him in the archives in France, Britain, the US, and Spain. Unlike most enslaved people, Toussaint Louverture left behind a trail of documentation and testimony, making possible a full-scale research project. But, the author insists, further such stories need to be written and told from the perspective of the colonised.

‘Although often slaves spoke numerous languages, most of the archives we have are European,’ he says. ‘And most slaves have left no written trace. So most of what has been written has been recorded from a European or colonial perspective.’

Sudhir continues, ‘This is the challenge we now face: to tell the story of those men and women who resisted slavery and colonialism...indeed there are so many others like him [Toussaint Louverture] and we need to recover their histories, celebrate their pioneering achievements, and bring them to wider audiences.’

But he insists, ‘The ethnicity of the historian does not matter. What matters is that they ask the right questions and scrupulously tell the story of black and colonised peoples. It can be done by anyone who has the right spirit.’

This is the challenge we now face: to tell the story of those men and women who resisted slavery and colonialism...and we need to recover their histories, celebrate their pioneering achievements, and bring them to wider audiences

Sudhir Hazareesingh

Sudhir is fascinated by how great individuals can change the course of history. ‘Exceptional people can make a difference ,’ he says. ‘Only 1% of enslaved people became emancipated in Saint-Domingue before slavery was abolished and these were often people with special talents, such as Toussaint Louverture.’

He adds, ‘Louverture turned an untidy, chaotic revolution and directed the energy of the former slaves, most of whom were African-born, and transformed them into a community, a people who shared a common destiny...He wanted Saint-Domingue to flourish under the French Republic – with equal rights for all citizens, and autonomy for the colony...the French didn’t have much choice, they went along with him because he made himself indispensable.’

It is some 40 years since Sudhir arrived at Balliol. It is said that you spend three years at university trying to forget people you meet in Freshers’ Week. He may be putting on a brave face, but he appears resigned to the fact that one of his undergraduate contemporaries will be part of his life for the foreseeable future. Boris Johnson is now Prime Minister, and rarely off our screens. Sudhir has taken a quite different path since their days together as students. He is the Senior Fellow at their undergraduate college, Balliol, an acclaimed author and has been made a Fellow of the British Academy.

He will certainly not be flattered by the suggestion, but it could be said the old contemporaries have quite a lot in common. Although he writes histories, albeit of people, Sudhir is a Politics tutor, teaching international relations. Mr Johnson has spent decades as a politician and, before that, wrote about politics. And he was, of course, put in charge of British international relations, as Foreign Secretary in Theresa May’s Cabinet. Meanwhile, Mr Johnson wrote a biography of his ‘hero’ Churchill – while Sudhir is an authority on Churchill’s often troublesome French ally Charles de Gaulle.

Exceptional people can make a difference...Only 1% of enslaved people became emancipated in Saint-Domingue before slavery was abolished and these were often people with special talents, such as Toussaint Louverture

There, the comparison very much ends, though. In fact, they could not be less alike. Sudhir is clearly much more interested in political life across the Channel. And he is evidently not attracted to his connection with the corridors of power, noting that his Freshers’ acquaintance had remained just that. He recalls his contemporary with wry amusement, ‘Boris [the Prime Minister] was exactly the same then...Same hair... And he had already mastered the art of getting by without over-exerting himself.’

The academic, meanwhile, went on to take a DPhil and has spent the last 40 years at Balliol, aside from a brief sojourn at Nuffield College as a Prize Research Fellow. Life at what is one of the university’s oldest colleges, suits him. ‘Balliol is easy going,’ he maintains. ‘And I’ve always felt at home here.’

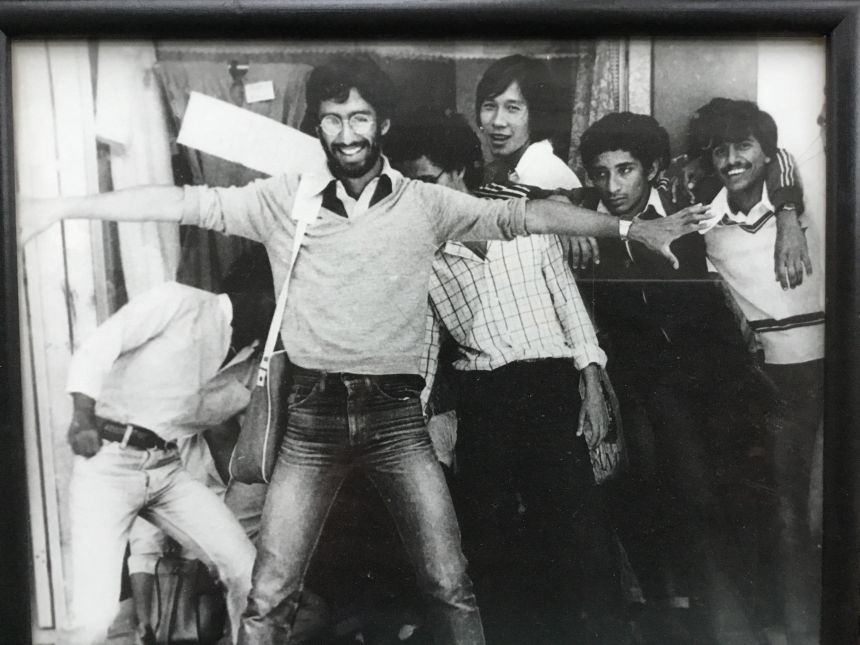

It was, actually, a very long way from home, in 1981, when the young Sudhir arrived at Balliol on a scholarship from his home in Mauritius, where he studied at the Royal College in Curepipe. Although it is a renowned and historic school, with a string of illustrious former students, from Cardinals to Prime Ministers, it was a world away from the playing fields of certain schools. See relaxed photo below.

He had been a studious boy, interested in academic pursuits - particularly history, literature, Latin and Greek. But he came to Oxford particularly to study politics, which was already a passion. Sudhir’s father Kissoonsingh Hazareesingh was a historian who had been involved in Mauritian public life and their house was a political hotspot. ‘An old member from Balliol, called Anderson, set up a scholarship for people from Mauritius – and I was lucky,’ he says. ‘I was fortunate to have this kind of support....the Anderson Fund is still there, but it doesn’t stretch as far these days, we use it to part subsidise a graduate scholarship.’

‘My father worked for the Prime Minister Sir Seewoosagur Ramgoolam and there always people talking about politics and culture in our home,’ he says. ‘I was immersed in this atmosphere growing up.’

Same expression, 1970s' style: Sudir and friends taking life less seriously

Same expression, 1970s' style: Sudir and friends taking life less seriouslyOxford in the early 1980s a very different place, he says, with domestic students not paying fees and far fewer people going to universities.

‘There was a much more healthy relationship with education,’ Sudhir recalls. ‘People studied subjects they were interested in. The atmosphere was different in that you learned something for its own sake, not to acquire a trade.

‘If you had asked any of my contemporaries what they planned to do as their career, they would have laughed. We didn’t think about education in that way.’

Perhaps one of them did, though, the one who had always wanted to be ‘world king’.

Sudhir insists, however, it could be possible for higher education to have a similar purpose today, and suggests countries such as Norway offer models for large scale tertiary level study. And, although he came nearly 10,000 miles to study Philosophy, Politics and Economics, he had no personal political ambitions and did not anticipate ‘where he would end up’. But he did know that he was not cut out to be an economist, and quickly dropped the E from his PPE.

‘I am practically innumerate,’ he says. ‘I was absolutely hopeless at Maths and Science.’

He became increasingly interested in international relations (in which he took a Masters) and in France. Mauritius had not been a French colony since Napoleonic times, when the British seized the island to become the new occupying force. But it retained aspects of French law and French is still widely spoken. For Sudhir, though, Mauritius will always be home and, until this year, he has been an annual visitor. But being close to France has been a major benefit of studying and living in England. He says, ‘Until the pandemic, I would spend four to five months there each year.’

He wonders if the French president himself, Emmanuel Macron, may not make the final run-off [in the presidential election]....‘He has only around 25% support, which is low for a sitting president. They usually have something like 30-35%

French politics is evidently a serious enthusiasm and he talks expectantly about the forthcoming presidential election. He says, rather hopefully, ‘Until 2017, I was confident the French would never elect someone who was bigoted...a populist demagogue like Marine le Pen [leader of the far-right Rassemblement National].’

But he has concerns about the next election and wonders if the French president himself, Emmanuel Macron, may not make the final run-off [under the French system, there are two rounds, with only the two most popular candidates making it through to the last and decisive election], ‘He has only around 25% support, which is low for a sitting president. They usually have something like 30-35%.’

He speaks with considerable incredulity about Macron’s refusal to contemplate reparations for Haiti. It is the poorest country in the western hemisphere, he says, because the French insisted that the newly free nation had to compensate French slave owners for the loss of their slaves.

‘The British did the same thing, but raised money through the Exchequer [to compensate slave owners],’ he says. ‘But the French demanded it from Haiti...in today’s money it amounts to about 30 billion Euros. That’s one of the main reasons why Haiti is so poor.’

Sudhir will be following events in France closely and, potentially, as in 2017, he may write about the election in the British and French press. The French political system is a source of great fascination, ‘It is a Republican monarchy...and some of the presidents [he mentions Giscard and Mitterrand] were very regal. But the position of president is difficult. [It suited] de Gaulle, he was a great war leader and a politician, but the others have just been politicians.’

It is a Republican monarchy...and some of the presidents [he mentions Giscard and Mitterrand] were very regal...the position of president is difficult. [It suited] de Gaulle, he was a great war leader and a politician, but the others have just been politicians

His fascination with individuals does not extend to wanting to meet them, however. He confesses he would not have cared to meet either de Gaulle or Napoleon.

‘I don’t think they would have been approachable. They were very solitary,’ he says. But Louverture? Sudhir says, ‘I would have loved to spend time with him, to learn more about him personally. He was a Catholic, but practised voodoo. He had a very close relationship with nature... everything was connected with him; he was part French philosopher, part Caribbean revolutionary, part son of Africa....there was so much information I unearthed about him, the book could have been twice as long.’

I would have loved to spend time with him...he was part French philosopher, part Caribbean revolutionary, part son of Africa....the book could have been twice as long

On Toussaint Louverture

And where is home now?

‘I prefer to think of myself as having lots of homes. My intellectual home is France. I was born in Mauritius but I have lived in Oxford for 40 years and this is home as well.’

‘But,’ he says wistfully, thinking of sunnier climes in his far-off retirement. ‘I am a tropical boy.’

By Sarah Whitebloom