From OPEC to Net Zero and still optimistic: Professor Nick Eyre on 34 years as an environmentalist

An environmental campaigner for 30+ years (and advisor to two Prime Ministers), Professor Nick Eyre is surprisingly buoyant in the circumstances. He laughs easily and maintains he is an optimist – because the alternative is too depressing. ‘What’s the point?’ he asks.

Now (sort of) approaching retirement, Professor Eyre offers a unique perspective on the history of the environmental movement, at a time when it has gone mainstream. When he commenced his interest, one of the great social issues of the day was the demand to keep coal mines open.

Although long focused on the need for energy saving, the eco-expert actually started out as a nuclear scientist. He had graduated in Physics from Oxford in the late 1970s and then took a doctorate in Nuclear Physics, before going to work for the Atomic Energy Authority at nearby Harwell. It was very much seen as the future in terms of energy. He laughs again, as he remembers the police, who then surrounded the Harwell facility and who were suspicious of his badge – from CND (another great social issue of the day).

The eco-expert started out as a nuclear scientist....going to work for the Atomic Energy Authority at nearby Harwell. It was very much seen as the future in terms of energy

'Energy-saving seemed a back water at the time,’ says Professor Eyre.

‘I was always a bit of a square peg in a round hole,’ he smiles in recollection. Not surprisingly, it was to be a relatively short-lived position. And, he took up an opportunity to work for the Energy Technology Support Unit (ETSU). It astonished his manager at the AEA, he says, for whom it was inexplicable, in those pre-climate conscious days.

‘Energy-saving seemed a back water at the time,’ he laughs.

‘It was a bit of a leap in the dark. It was very niche. But I wanted to do something I believed in - and I was lucky to find it,’ says Professor Eyre, who started on the path, which he still treads, 34 years ago.

But he has not had a conventional academic journey. For many years, he worked in the public sector and as an environmental consultant to policymakers. He only returned to Oxford some 14 years ago and is now Professor of Energy and Climate Policy, and Senior Research Fellow in Energy at Oxford’s Environmental Change Institute, and Director of the Centre for Research into Energy Demand Solutions, which is the hub for energy demand research in the UK. He is also the End Use Energy Demand Champion for UK Research and Innovations' Energy Programme and Interim co-director of Oxford’s new Zero Institute, which brings together researchers from across the University to tackle questions surrounding zero-carbon energy systems. Plus, he is Co-Director of the Oxford Martin Programme on Integrating Renewable Energy, And, Professor Eyre volunteers as scientific adviser to Oxford City Council. So, he is quite busy.

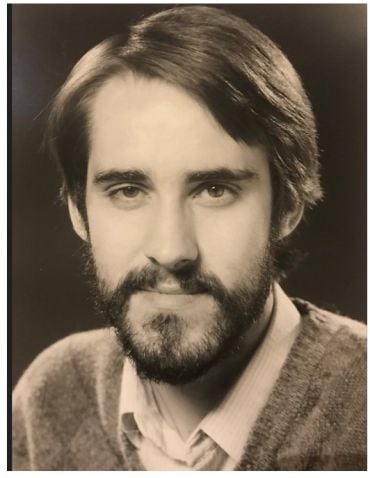

Young Dr Eyre

Young Dr EyreBut ETSU came up with a lot of recommendations which might also seem familiar today – including using wind turbines. Energy saving was nothing new, though, even then, he says, reflecting on people from the wartime generation, such as his parents, who were accustomed to rationing and energy saving.

In 1989, he and colleagues drafted a report on the climate threat for the then Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher....More than 10 years later, Professor Eyre was...explaining, for the benefit of the new Labour Prime Minister, Tony Blair, why climate change was important

‘They had a very different approach, generally being frugal-driven,’ he says. ‘But they were better at some of the consumer behaviour [than consumers today].’

Growing up in Yorkshire, the young Nick had an early interest in the environment, thanks to his parents. His father was a soil scientist at Leeds University, he says, and the family was very interested in the world around them, ‘I was brought up to know about plants and animals…and my mother was a primary school teacher.’

But, by the late 1980s, climate change was emerging as a concern and the young Dr Eyre was very much in the forefront of thinking about energy policy and efficiency. He remembers, ‘I was the first person to work for the Department of Energy on climate change…it was a bit of publicity; nobody took it very seriously.’

By the late 1980s, climate change was emerging as a concern and the young Dr Eyre was in the forefront of thinking about energy policy and efficiency. He remembers, ‘I was the first person to work for the Department of Energy on climate change…it was a bit of publicity; nobody took it very seriously.

But it did lead, in 1989, to him (and colleagues) drafting a report on the climate threat for the then Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher. She famously went ‘green’, startling the international community and claiming eco credentials - to the amazement of many.

In the subsequent decade, Professor Eyre explains, the 1992 Rio summit and the 1997 Kyoto meeting established that action was needed. Nevertheless, concerns were not particularly widely held. Professor Eyre muses, ‘It didn’t really reach the public consciousness until the school strikes and Greta [some two decades later].’

When they wrote the paper for Mrs Thatcher, Professor Eyre says, they forecast the likely situation in 2020. He says, ‘We predicted energy saving pretty well, we understood renewables...If people had started then, though…you always could do more.’

He adds, ‘What that crisis created, could have helped to solve the crisis now.’

Thinking of the current international fuel situation, Professor Eyre points out, ‘We’re too dependent on gas – although it’s easy to be wise after the event. But, if we’d kept on with our energy saving programmes, things would be very different now…At the moment, though, we’re subsidising people to burn gas [because they need heat in their homes] – you can’t solve problems overnight.’

Does he mind that it has taken so many years, arguing the same thing, before environmental concerns have moved up the agenda? Professor Eyre laughs, ‘There has been an evolution in views on the importance of energy use.’

Does he mind that it has taken so many years, arguing the same thing, before environmental concerns have moved up the agenda?

Professor Eyre laughs, ‘There has been an evolution in views on the importance of energy use.'

Since the Thatcher paper, there has been considerable political and social change, says Professor Eyre, ‘Who could have predicted all that has happened or the innovations that have made a difference?’

Professor Eyre became an independent consultant after Harwell and began undertaking environmental policy work more widely. He says, the European Commission was a regular client and wanted him to say how much environmental issues were going to cost. He remembers, ‘We tried to put a value on climate change – and it was enough to show how important it was.’

Despite mainly working in London, he remained living in Oxford and was an Oxfordshire County Councillor from 1987. Professor Eyre says, there were some things they managed to get done, such as nursery provision – and, he says, ‘Most councillors were old-fashioned. They tended to be elderly men with traditional views.’

He, meanwhile, had a claim to be the most left-wing person on the Council, he laughs again. Professor Eyre remained on the council for six years, but it put him off the idea of a career in politics, particularly when he saw how hard MPs have to work, ‘It’s a tough job to do well.’

But he went back into the public sector, as Head of Policy at the Energy Saving Trust, and was working near the corridors of power in the late 90s when power changed hands in the House of Commons. More than 10 years after his paper for Mrs Thatcher, Professor Eyre was working with the Cabinet Office and explaining, for the benefit of the new Labour Prime Minister, Tony Blair, why climate change was important. Now situated in Admiralty Arch, he recalls, ‘I knew enough about government, to know they do things slowly.’

‘We estimated the UK could reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 60% by 2050,’ he recalls. ‘It doesn’t sound very exciting now, but then it seemed very ambitious.’

But his time with the Cabinet Office showed him the complexity of government, with every department and office involved and consulted on almost every issue, ‘It was very political. A number of departments had a say...we reached an impasse with Energy and the MoD.’

Laughing, he says, ‘If you were going to organise a conspiracy in Whitehall, you would want only two conspirators, because otherwise it would leak, and preferably only one, which wouldn’t be much of a conspiracy.’

His Cabinet Office paper was finally put in front of Tony Blair at a meeting in Westminster. Green issues were firmly on the table – where they have remained, to a greater or lesser extent, ever since.

His Cabinet Office paper, though, was finally put in front of Mr Blair at a meeting in Westminster. Green issues were firmly on the table – where they have remained, to a greater or lesser extent, ever since. In the UK at least, the environment has not become a polarising political debate – but Professor Eyre is concerned it could become so.

‘We could go the way of the US or Australia, where politics trumps science – and I say trump deliberately,’ he says ruefully. ‘It doesn’t matter what science says [for some] because they are seeing it through a different lens. There has been a huge disconnect…the idea that there is some conspiracy is ridiculous.’

He says ironically, ‘What, the IPCC [the international panel on climate change] is part of some conspiracy? There are hundreds of scientists involved – you couldn’t get them to agree on anything.’

Leaving behind government and the Energy Saving Trust, Professor Eyre returned to Oxford in 2007, after decades away, to take up a research fellowship at the Environmental Change Institute.

‘They took a gamble on me. They probably didn’t realise how much of a gamble,’ he beams. ‘I’d done lots of research, but I had never worked in a university. But the ECI does work that makes a difference and I am so pleased we have been able to build up our group [working on energy demand and decision making]. It’s full of really great people.’

Professor Eyre talks of the research being done at the university into renewables and systems and about his work with CREDS (The centre for research into energy demand solutions) which brings together researchers from 20 universities, looking at solutions to energy needs.

‘We’ve got to reduce energy use by half by 2050. That’s going to mean huge changes in buildings, transport and manufacturing…no one thing is going to solve climate change

Professor Eyre does not underestimate the challenges ahead

‘We’ve published about 100 academic papers in four years,’ he says, evidently impressed at the output of his colleagues. But he does not underestimate the challenges ahead.

‘We’ve got to reduce energy use by half by 2050. That’s going to mean huge changes in buildings, transport and manufacturing…no one thing is going to solve climate change.’

Although a life-long campaigner, Professor Eyre does not see easy solutions. He emphasises it is a complex issue, which needs careful thought and negotiations. He points out that developing countries, some of which have not undergone electrification, have different concerns, ‘We need to think in a fair and equitable way. There are complex sociological and technological problems. Those complexities need to be thought through.’

Professor Eyre insists we each need to be thinking about introducing energy saving measures – such as insulation, heat pumps and electric vehicles. But he maintains, ‘We’re not going to stop climate change by persuading seven billion people individually to change their ways.’

He maintains, ‘We need public policy, committed to [environmentally-friendly] projects and committed to changing infrastructure and with substantial goals.’

We’re not going to stop climate change by persuading seven billion people individually to change their ways

Professor Eyre

Oxford, he insists, has world-leading energy use research underway, ‘Ground breaking solar, battery systems, fuels. There are people doing amazing things…but there are big big challenges and there has to be an inter-disciplinary response.’

Part of that has been the establishment of the Zero Institute in Oxford, of which Professor Eyre is an interim co-head. It brings together researchers from across the University to tackle questions surrounding zero-carbon energy systems – including looking at heating and cooling and reducing energy use. It is all about making a difference.

It’s easy to be gloomy at the moment…But there is no point in arguing with people for not doing something. Everyone needs to be on board

Professor Eyre

In a scene from Tomorrow’s World, n the empty car park outside Professor Eyre’s post-industrial office, a young researcher is conducting an experiment to create a more energy and water efficient dishwasher. Work such as this could make a significant difference going forward.

‘It seems to be working,’ she says.

Reflecting on the international political situation and the climate emergency, Professor Eyre said, ‘It’s easy to be gloomy at the moment…But there is no point in arguing with people for not doing something. Everyone needs to be on board.’

And the former politician clearly understands only too well how important that is.

By Sarah Whitebloom