Women academics don't realise how amazing they are - says (the amazing) Prof Lucie Cluver

Professor Lucie Cluver looks a mixture of embarrassed and astonished, this number is woefully inaccurate, she says. She and colleagues are about to publish a paper showing that 5.2 million children internationally have been orphaned during the pandemic. It is a huge number, approaching the populations of eight large UK cities. But, the Oxford parenting expert confides, new estimates show there has been an under-reporting of deaths on a scale of 10 times in Africa.

‘When we take this into account, there are actually seven million children orphaned by Covid, with most of the missing children coming from Africa.’ she says, horror in her voice. These are children who have lost a main care giver.’

A busy WhatsApp conversation with colleagues around the world ticks away in the background, as the international team tries to make sure the new number is accepted by key health authorities. These are not just figures on a screen. Professor Cluver apologises and explains, ‘It is really important they have the right numbers. It could have a serious impact on the amount of funding that is given, and where it goes.’

Professor Cluver has form in this space. At the beginning of the pandemic, she and colleagues thought about what the pandemic was going to mean for children and families. Lockdown, school closure and stress are a recipe for child care challenges and child safety concerns.

In a few days, in March 2020, they created a Covid-19 pack of parenting advice...It has to be one of the most successful pieces of academic research ever delivered. The parenting resources have been used by more than 210 million people

In a few days, in March 2020, Professor Cluver, Dr Jamie Lachman and colleagues created a Covid-19 pack of parenting advice. Based on years of academic research and rigorous testing, this was launched into a global testbed and available free of charge from health authority websites around the world.

‘It has turned up everywhere,’ says Professor Cluver, who is quick to name-check others who have contributed. ‘Doctors’ waiting rooms in Washington DC, the WHO website, handed out by monks in Nepal.’

It has to be one of the most successful pieces of academic research ever delivered. The parenting resources have been used by more than 210 million people, in 198 countries and by 33 national governments in their Covid programmes.

It has been used in national parenting guidelines in Kenya; child welfare remote training protocols in Thailand; Covid-19 health promotion in Guatemala; promotion by Namibia’s and Paraguay’s First Ladies; and national casework guidance in South Africa.

It [the parenting advice] has turned up everywhere. Doctors’ waiting rooms in Washington DC, the WHO website, handed out by monks in Nepal

Professor Lucie Cluver

They are being used in maternity care in Zambia and paediatric consultation in Pakistan; phone mentoring programmes in India; emergency parenting hotlines in Montenegro, Malaysia and Philippines; online curricula in Ghana and educational games in Nigeria. They have been on TV and radio in Jamaica, Kyrgyzstan, Pakistan, South Africa and Zimbabwe. They have been handed out in food parcels in refugee camps by UNODC and delivered to 5,800 villages in Lao PDR and Cameroon through community loudspeakers.

This is not ‘give them a hug’, aren’t the kids great-style advice. Professor Cluver is a professor of child and family social work in the Centre for Evidence-Based Social Intervention in Oxford’s Department of Social Policy and Intervention – with the emphasis on evidence. And their work involves the sort of scientific randomised controlled trials more usually associated with, say, vaccine development.

The young researcher in South Africa

The young researcher in South AfricaBut no sooner was this project delivered than concerns were raised about the likelihood of large numbers of orphaned children. And Professor Cluver’s attention has once more been diverted.

This is not ‘give them a hug’, aren’t the kids great-style advice....their work involves the sort of scientific randomised controlled trials more usually associated with, say, vaccine development

‘I was contacted by a brilliant colleague – Dr Susan Hillis - at the American CDC (Centre for Disease Control) who said we have to do something about this, urgently,’ she says.

‘I was bullied into this really,’ she laughs.

An international team sprang to life and it was clear, the human legacy of the pandemic will long outlive the lockdowns for nearly seven million children in particular. She, in turn, roped in leading statistical modellers, one of whom was Dr Seth Flaxman in Computer Science, a fellow parent at her child’s university nursery.

The team used data from around the world to estimate the numbers of orphaned children and calculate the financial need, which was informed by the experiences of AIDS-orphaned children in South Africa.

As the full extent of the problem was understood, it became clear, action was needed at the highest level and the team is currently negotiating with policymakers and governments.

It is the latest in a series of diversions for Professor Cluver, who actually never wanted to be an academic. Her ambition was to be a children’s social worker.

Professor Cluver never wanted to be an academic. Her ambition was to be a children’s social worker...but there was no social work degree then, so she went to Cambridge to study Classics

‘I had done voluntary work before I went to university,’ she says. ‘And I always knew I wanted to be a social worker, working with children. It was my only ambition.’

But there was no undergraduate social work degree then, so the young Lucie went to Cambridge to study Classics, under such luminaries as Professors Mary Beard and Keith Hopkins.

‘I wasn’t very good at the languages,’ she admits with amusement, although it might be thought to be a requirement of Classicists. ‘But I loved the stories and the history. I was quite undeterred by being useless at Greek.’

Recalling her attempts at the ancient language, Professor Cluver adds, ‘Just before my finals, my Mum bought me a tea towel with the Greek alphabet on it. It was really useful.’

She says, ‘My lack of talent was offset a bit by working really hard.’

How do you go from there [being useless at Greek] to become Oxford’s youngest-ever female full professor, just seven years after completing a doctorate?

How do you go from there, to become Oxford’s youngest-ever female full professor, just seven years after completing a doctorate?

After Cambridge, the young graduate applied and was accepted for a Masters in social work at Oxford. Not a natural move, it would appear. But her application was aided by all the volunteer work she had been doing (unbeknown by her tutors) as an undergraduate. She had never quite gotten round to mentioning to them, she laughs, that she had written most of her essays whilst doing night shifts at Jimmy’s homeless shelter.

‘When I got here, it was an amazing course, led by Professor Frances Gardner. It was ground breaking and evidence-based, which was very unusual at the time,’ she says. ‘Now it’s morphed into the Masters in Evidence-based Intervention and Policy Evaluation.’

Her plans to be a social worker were blown off course and into academia by a placement in South Africa.

‘My mother came from South Africa, but it was a real shock going there. On my first day, I turned up at my workplace and there was a sign outside saying “gun free office”. Inside, there was a massive pile of files...that was my placement.’

My mother came from South Africa, but it was a real shock...I turned up at my workplace and there was a sign outside saying “gun free office”. Inside, there was a massive pile of files...that was my placement

Professor Cluver

It was the height of the AIDS epidemic and before South Africa had antiretroviral drugs. Most of the cases in those files involved children orphaned by AIDS.

‘I did a small thesis, looking at what orphaned children needed,’ she says. ‘But more work was needed and the obvious thing was to get the funding for a doctorate.’

This allowed her to conduct a wider study, with a thousand children.

‘There were severe mental health problems associated with losing a parent to AIDS,’ recalls Professor Cluver. ‘And a range of other challenges. Violence is a real issue.’

‘I was introduced to the minister of social development by a professor who had been his cell mate during the struggle against apartheid. He told me that this was a start, but they needed a national study.’ So I went back and raised money to do that.

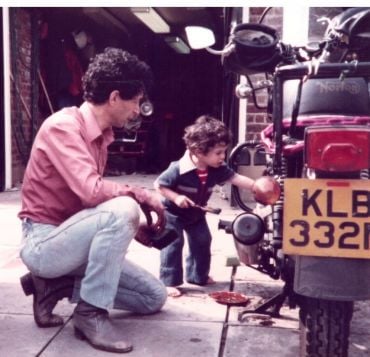

Practical as ever, Lucie, helping mend her father's motorbike

Practical as ever, Lucie, helping mend her father's motorbikeOne of her key findings, which has had a wider impact on support in developing countries, has been that cash transfers make a big difference to the lives of children in general, girls in particular. It may sound obvious – or some may argue that it is better not to give actual cash. But Professor Cluver insists, ‘Girls are much less likely to have transactional sex if money is going into the family...The evidence is there that, if there is $20 a month is going into a household, then the likelihood of teenaged girls having to get a boyfriend to put food on the table falls by 50-70%.’

One of her key findings...has been that cash transfers make a big difference to the lives of children in general, girls in particular....‘Girls are much less likely to have transactional sex if money is going into the family...The evidence is there

Such evidence, gathered during her research in South Africa, underpins the urgency now to ensure funding is provided for children orphaned by Covid, especially in the global south.

‘Family violence is also such a problem – with AIDS and Covid,’ Professor Cluver says ‘But all the evidence-based programmes were commercialised.’

Discovering that there was no free-to-use parenting guidance, she and a team of colleagues decided to create some. Randomised controlled trials were key to the work – with many led by Dr Lachman and Professor Gardner – which is all available free on the WHO website. This is very much ‘hard science’. She says, ‘We have done a study involving 130,000 participants.’

But it is also science which responds rapidly to events.

‘It’s a different way of doing research, you can’t always predict what needs to be done,’ says Professor Cluver, with an eye on the WhatsApp messages. ‘We have an international team and we just ramped up [when the pandemic started]...and I’m back with orphaned children again.’

Professor Cluver admits that, having her own children, has made her think differently. She smiles, ‘It’s made me much more sympathetic to parents...it is really stressful and everyone makes mistakes every day. Single parents deserve medals.’

Having a workplace nursery at St Anne’s College was a major factor, she says, in being able to conduct academic work and produce the amazingly successful parenting advice. But she points out, ‘There are no part time professorships here.’

But, she says, being at Oxford makes it possible for academics to pursue their own interests and avenues, ‘That’s the thing I love about Oxford...other people don’t have that freedom.’

She worries, though, that some female academics do not look at themselves and realise how amazing they are – so do not apply for positions or promotion.

‘I wish they would have the confidence to see what others can see in them,’ she says, adding earnestly, ‘I had some amazing advice from a senior woman once: if you’re successful, some people will hate you...get over it.’

I wish they [other women academics] would have the confidence to see what others can see in them...I had some amazing advice from a senior woman once: if you’re successful, some people will hate you...get over it

Professor Cluver

It is advice she is ready to share. But it is hard to believe anyone is sticking pins in a small effigy of her. Although her work has gone around the world and she was the youngest-ever female full professor, Professor Cluver is friendly, relaxed and appears endlessly enthusiastic - as befits a would-be social worker. And, if anyone is sticking in pins, she is clearly far too busy to worry. Professor Cluver says, ‘Every time I think I know what I am doing, the next crisis comes along...something else will turn up soon.’

(In the last week, Professor Cluver and her Oxford colleagues have been part of an international team creating parenting advice, with UNICEF and the WHO, for families affected by the crisis in in Ukraine. Designed for social media, it has been produced at break-neck speed with the assistance of numerous researchers, staff and volunteers).

‘But the thing is,’ she says, closing. ‘Our research tries to make people’s lives better.’

And with that, she returns to her WhatsApp feed – and the effort to ensure international funding is provided for seven million new orphaned children.

Lucie Cluver is Professor of Child and Family Social Work at the Department of Social Policy and Intervention, and a Professorial Fellow at Nuffield College.

By Sarah Whitebloom