Professor Carolyn Hoyle, academic, advocate, campaigner: 'The death penalty is not ok anywhere.'

Criminologists have been staples of TV crime drama for decades. The fictional versions solve cases that have baffled the police, or get inside the heads of serial killers.

‘We don’t do anything like that,’ says Professor Carolyn Hoyle of Oxford’s Centre for Criminology. ‘No one here works on solving crimes. We work on criminal justice, the way the system works and deals with offenders, policing, sentencing, victims’ experiences, as well as related fields such as the detention of migrants.’

Professor Hoyle adds, ‘In the course of my career, I’ve conducted research on the policing of domestic violence, restorative justice, crime victims and decision making within the official body that’s supposed to correct miscarriages of justice. Uniting the various areas of my research over the decades has been an interest in discovering what shapes decision making.’

I’ve conducted research on the policing of domestic violence, restorative justice, crime victims and decision making...After all that, I’m now focused on just one area – the death penalty

But, she says, 'After all that, I’m now focused on just one area – the death penalty and its application, especially in Asia and Africa.’

Professor Hoyle continues, ‘A friend once accused me of being “intellectually promiscuous”. She was right, I got easily bored, but for the rest of my career, I’ve decided to concentrate on this one thing, because it’s where I think – or at least, I hope – I can make a difference. My challenge now is taking the theoretical and empirical work I have done in the past and using it in my work on the death penalty. It has been a real shift in my working life.’

Since 2021, Professor Hoyle has been Director of the Death Penalty Research Unit, which she set up in the Centre, partnered with The Death Penalty Project, a pro-bono department based in a London law firm, Simons Muirhead Burton.

There is no doubting Professor Hoyle’s commitment to a field where the stakes of research and advocacy involve matters of life and death, though the conversation is punctuated by her laughter. As for the Centre, she says, ‘It’s one of the busiest centres within the Law faculty, very research active.’

There is no doubting Professor Hoyle’s commitment to a field where the...research and advocacy involve matters of life and death, though the conversation is punctuated by her laughter

She explains, ‘ Most of our students are graduates, from different disciplines and jurisdictions… their intellectual perspectives are diverse… and seminars inevitably stimulating.’

Professor Hoyle came into criminology through a Sociology Masters. In those days, Oxford did not offer a Master’s in criminology. She would later play a central role in designing the MSc in Criminology.

She was keen to take a criminology option, at that stage, intending to go on to Law School and then to qualify as a criminal lawyer. Unfortunately, that year the late Professor Roger Hood, the director and father of the Centre for Criminology, was on sabbatical. So, she had to persuade him to take her on as a student, during his break.

‘I sent him a letter and we had tea at All Souls – which was very special,’ she recalls. ‘He agreed to put on the course for me. I wanted to do feminist criminology, so he asked me to design my own course. We went on to have one-to-one tutorials. Very Oxford. It was Roger who later persuaded me to do a DPhil.’

Her DPhil research focused on domestic abuse. At the time, as now, few cases resulted in a conviction.

‘As part of my research, I went out with police as they answered calls; meeting victims and tracking what happened to them. I looked into well over 300 cases.

‘I was interested in police and prosecution decision-making: how it was that all these cases came into the system and only a few made it to conviction. I found shortcomings among police and prosecutors weren’t the only reason why cases didn’t get to court. Sometimes victims didn’t want their partners or former partners prosecuted, and were reluctant to give evidence. Some came to believe their own interests and those of their children might be better served if they didn’t.’

Sometimes victims didn’t want their partners or former partners prosecuted, and were reluctant to give evidence...Three of those cases she examined were eventually murdered by their current or former partners

Three of those whose cases she examined were eventually murdered by their current or former partners, ‘That really got to me. Self-evidently, they had been let down – and these were women who had taken that difficult step of contacting the police. Most domestic violence victims won’t do this until they’ve been attacked numerous times.’

This work was published in 1998 (Negotiating Domestic Violence), as part of OUP’s Clarendon Series – which Professor Hoyle now co-edits with her Centre colleague, Professor Mary Bosworth. It formed the start of her continuing interest in the complexities of decision-making as it affects criminal justice.

‘A lot of my work deals with the gap between the law in books, and the law in action,’ she says.

Professor Hoyle’s work on miscarriages of justice – a landmark study on the Criminal Cases Review Commission (Reasons to Doubt) - fed naturally into her interest in capital punishment. After all, she points out, ‘reversing a wrongful conviction when someone is serving life in jail is a wrong that can still be put right. There is no way back from the execution of an innocent or undeserving prisoner’.

Reversing a wrongful conviction when someone is serving life in jail is a wrong that can still be put right. There is no way back from...execution

The death penalty is an interest she shares with her husband, the journalist David Rose, whose book, Violation, dealt with the case of an innocent man who was put to death in the Deep South state of Georgia.

‘You can imagine our dinner table conversations,’ she says.

However, Professor Hoyle’s main areas of study lie not in America, where academics have long been actively studying the death penalty, but the rest of the world, where thousands of people are executed every year.

Professor Hoyle says she is sure the deputy Tory Party chair Lee Anderson MP's recent call for the return of capital punishment in Britain would not be popular, ‘Maybe it would have been, two or three decades ago. But when you ask people whether they want this in reality, bearing in mind the scepticism over how well the criminal justice system works, you get a different response. Research shows trust in it is quite low, and, not surprisingly, people don’t want innocent people executed.’

The same is true in the jurisdictions where Professor Hoyle and her colleagues work, ‘If you describe actual cases, along with evidence that those sentenced to death tend to come from deprived backgrounds with multiple social problems, and if you show they were served poorly by their lawyers, support for capital punishment declines. Add in evidence of wrongful convictions, and support falls dramatically.’

If you describe actual cases, along with evidence that those sentenced to death tend to come from deprived backgrounds...they were served poorly by their lawyers, support for capital punishment declines

Despite her current role, Professor Hoyle had to be persuaded by Roger Hood to take up research in this area. She was initially reluctant, in part, because the death penalty is international, and her two sons were then young.

‘The nursery shut at 6pm,’ she says. ‘So, inevitably, I was very UK focused.’

She thinks and admits, ‘There was a gendered aspect to my decision to delay doing international research.’

But eventually her mentor won her over.

‘He was persistent,’ Professor Hoyle says. He was already an internationally-acknowledged expert, about to start work on the fourth edition of his important work: The Death Penalty: A Worldwide Perspective.

‘Roger was an incredibly powerful influence on me,’ she says. ‘I thought, ok, maybe I should get involved….and as I had already taken over teaching his death penalty course, after his retirement, it made sense to agree to co-author the 4th edition, published in 2008, and then the fifth, which came out in 2015.’

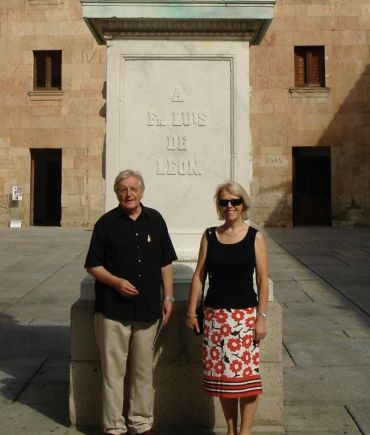

Professor Hoyle in 2011 with her mentor the late Professor Roger Hood

Professor Hoyle in 2011 with her mentor the late Professor Roger HoodIt is now 18 years since she started working in the field that led to her founding the DPRU. She says, ‘The last lunch I had with Roger was in January 2020. I suggested setting up the Death Penalty Research Unit and he thought it was a fantastic idea, asking if he could be involved in some way…it was very sweet and humbling. Covid delayed its launch until 2021, and by then he had passed away. It remains a legacy, a tribute to his commitment to research on capital punishment and the wider abolitionist cause. I guess I do think of myself as carrying the baton that he passed to me.’

Her work...now involves...efforts to use [death penalty] research to engage with civil society and political elites and especially with those with the power to abolish it

Her work with The DPP now involves not only research on the death penalty but efforts to use that research to engage with civil society and political elites and especially with those with the power to abolish it. These countries currently include Kenya, Ghana, Zimbabwe, Indonesia, Taiwan, Malaysia and other Southeast Asian jurisdictions where people can be executed not only for crimes of violence but for dealing in narcotics.

‘My work has changed - I do more advocacy than most academics,’ she says. ‘I also do a lot of research on public opinion because that is thought to be the key barrier to abolition in most countries. One of the best arguments to persuade a government to abolish is to show support for the death penalty is much weaker than they fear, so they’re not running a big political risk if they abolish.’

One of the best arguments to persuade a government to abolish is to show support for the death penalty is much weaker than they fear, so they’re not running a big political risk if they abolish

Professor Hoyle says, ‘It might look as if, by focusing on one particular punishment, my intellectual scope has narrowed, but I research the various stages of the justice process that lead to capital punishment as well as the experiences of being on death row. And, for the first time, I research the pathways to, and motivations for, engagement in crime, which I have not previously been interested in, as I try to test deterrence theory in relation to drugs and the death penalty in Southeast Asia.’

Recent work by the DPRU and DPP in Kenya casts doubt on the claim that execution deters people from crime.

Recent work...in Kenya casts doubt on the claim that execution deters people from crime...95% of those convicted of robbery did not know that it was punishable by death

‘Those sentenced to death in Kenya for robbery with violence are not criminal masterminds. They often have a lot of financial dependents and are poor and uneducated. We interviewed 671 people who had been sentenced to death and, as elsewhere, found them to be the disadvantaged and the vulnerable.’

Professor Hoyle points out, ‘95% of those convicted of robbery did not know that it was punishable by death and inevitably most were not worried about a death sentence…the preconditions for being deterred were clearly not met.’

Many countries retain the death penalty, but have not executed anyone for at least a decade, defined as ADF - abolitionist de facto. This is another facet of Professor Hoyle’s work: as she points out, ADF status can end when there is political change. This is why she is working with The DPP in Ghana, Zimbabwe and Kenya, where they have not executed anyone for decades.

Her work with The DPP in one ADF country - has borne fruit. In 2021, cooperating with civil society organisations on the ground, their efforts helped to persuade Sierra Leone to abandon the death penalty.

‘I was a very small cog in the wheel, but it was a satisfying,’ she says. She is hopeful Ghana could abolish later this year.

But are there any cases in which she thinks the death penalty is justified?

‘My kids used to ask me this – and I admit, I wouldn’t lose any sleep over a case such as Adolf Eichmann [who was executed by Israel in 1962]. Do I regret he was executed? Not at an emotional level: he was partly responsible for the Holocaust. But such cases are extremely rare, and they don’t justify retaining capital punishment, anywhere, ever. What’s more, even in his case, I would have preferred the state to have put him on trial, and sent him to prison for life.’

I wouldn’t lose any sleep over a case such as Adolf Eichmann [who was executed by Israel in 1962]. Do I regret he was executed? Not at an emotional level: he was partly responsible for the Holocaust. But such cases are extremely rare, and they don’t justify retaining capital punishment, anywhere, ever.

Ultimately, Professor Hoyle says, the issue comes down to the role we want for the state.

‘I completely understand the emotional impulse a victim’s family might have to want to hurt somebody who has killed someone you love. As a parent, I get that. But I don’t want the state to be my avenger. The whole process of capital punishment is dehumanising and barbaric, and life on death row is a form of torture. In some countries, such as Japan, a prisoner will wake up every day not knowing whether it will be their last, because they are given no advance warning of execution. That’s not ok in an advanced democracy. It’s not ok anywhere.’

By Sarah Whitebloom