Professor Aditi Lahiri, CBE FBA MAE

Professor Aditi Lahiri is often exasperated at the very notion that there is little value in studying Humanities.

‘It is the Humanities which help us understand others through their languages and histories and allow us to deal critically and logically with complex and often inadequate and deficient material,’ she says. ‘And they also teach us to weigh evidence sceptically and consider more than one side of every question.’

The British Academy Fellow, and Vice President of Humanities, who was part of the initiative that launched SHAPE, in response to the general push to promote STEM subjects, points out, ‘The Humanities show what make us human.'

The Humanities show what make us human...we have forgotten how to sit and think. What's the impact of that going to be?

Professor Aditi Lahiri

‘The problem is,’ Professor Lahiri says. ‘We have forgotten how to sit and think. What’s the impact of that going to be?’

Professor Lahiri’s vehemence comes after decades as a ‘hard core’ Humanities academic. Now approaching retirement, she has studied and worked in universities across the globe and is a leading figure in the world of Linguistics.

Professor Lahiri has received many honours across the world. One of the first awards acknowledging her research was the Max Planck prize for International Cooperation, awarded by the Alexander von Humboldt Association in 1994. She was also awarded the German Leibniz Prize (by the German Science Foundation) in 2000, the highest academic award in that country. (She is pictured below, among other Leibnitz prize winners and the DFG President, Professor Ernst-Ludwig Winnacker, 7th from right, who said at the event, 'We do not look at passports when we give awards, all that counts is excellence in research.')

Leibnitz prize winners

Leibnitz prize winnersLinguistics sounds a fascinatingly serious academic endeavour – with codes, ancient scripts, logic – as well as brain-imaging machines. Linguistic experts in the Faculty include philologists (focusing on historical and comparative linguistics), theoretical linguists examining structures of languages, ancient and living, phonetics as well as neurolinguistics. And, listening to Professor Lahiri talk about her subject, it is impossible not to wonder why one did not study Linguistics and feel rather embarrassed and regretful about it.Meanwhile, in the UK, she was presented the Vice Chancellor's Innovation Awards, Inspiring Leadership in 2018 and last year, she received a CBE for services to Linguistics.

[Linguistics] sounds a fascinatingly serious academic endeavour

Researchers in Professor Lahiri's Language and Brain Laboratory, which she established soon after she arrived in Oxford some 14 years ago, address questions on how the brain processes language structure, particularly the structure of sounds and how they are put together, and of words as they are built up from their parts.

Commissioned by the University of Oxford, this portrait of Professor Lahiri is by the artist Rosalie Watkins.

Commissioned by the University of Oxford, this portrait of Professor Lahiri is by the artist Rosalie Watkins. Human speech is extremely variable and no individual can even say their own name twice in an identical fashion. Nevertheless, we understand each other very efficiently, even in our usual noisy environments. How? Finding an answer involves the study of how language is acquired, how it changes, and how our brains process speech.

Professor Lahiri is positively evangelical about the study of language and persuasively engaging. If a language is not your own native language, it seems very difficult. But every language has a set of rules, although native speakers do not consciously know them. Of course, spelling and pronunciation do not necessarily go together, she says, partly because spelling rarely catches up with the way language changes.

'In English, all words beginning with <p t k> are pronounced with a puff of air, i.e., aspiration,’ says Professor Lahiri. ‘But not if these sounds have a preceding <s>: thus pill [pʰɪl] vs. spill [spɪl].’

She explains, ‘This rule is relevant for English and German, but does not hold for example for French or Dutch. It is not a question of individual articulatory constraints, but part of one's language system.'

Professor Lahiri continues, ‘Difference in word classes can also be marked in different ways. In English, the same word can be used as a noun and a verb - identically pronounced: to ánswer ~ an ánswer.

'However, certain words of two syllables which have been borrowed into English from Latin or Old French can have two possible positions to place main stress: pérmit / permít or tórment / tormént.

‘The first word in each pair is the noun and the second is used as a verb. Generally, for similar pairs if they differ in stress, they follow the same pattern: stress on the first syllable if it is a noun, stress on the second syllable if it is a verb. But of course, languages always have exceptions, but often these are not random either.'

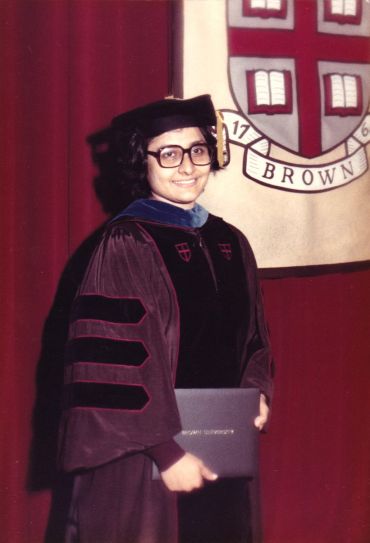

The young Dr Aditi Lahiri, winning her doctorate at Brown.

The young Dr Aditi Lahiri, winning her doctorate at Brown.It is impossible not to be intrigued by Linguistics. Professor Lahiri’s explanation leaps from word to word, highlighting how the commonplace can be very intricate, 'Think about use as in 'the use of a pen' and 'to use a pen' ". The spelling is the same, but 's' is pronounced differently with and without voicing, in the first and second use, like in a goose and to fuse, distinguishing a noun from a verb.'

The Professor says, 'There are some rules which have not changed in a long time.'

'Past tense of verbs such kiss is kissed and pronounced [kɪst], the rule being that the suffix [d] becomes /t/ if preceded by similar unvoiced sounds but remains a [d] after voiced sounds; compare moan ~ moaned [moʊn ~ moʊnd]. This pattern has existed for centuries: cf., Old English e.g., cyssan 'to kiss' cyste 'kissed' but mǣnan 'to moan' ~ mǣnde 'moaned'. We have continued to kiss and moan.'

Originally, Professor Lahiri took Maths at university, but switched to Linguistics as many others have done. She followed her parents into academia. They had both studied Philosophy at the University of Calcutta, having had the privilege of being taught by Professor Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan (second President of India and former Spalding Professor of Eastern Ethics at Oxford).

One difference was that Bethune girls (at the University of Calcutta) could obtain university degrees right from the very beginning [whereas women at Oxford did not receive degrees until 1921]

Professor Lahiri

Her formidable mother taught Philosophy at Bethune College under the University of Calcutta, which, she says, was interestingly founded the same year as Somerville College, with which she is currently associated.

‘As I understand it, one difference was that Bethune girls could obtain university degrees right from the very beginning [whereas women at Oxford did not receive degrees until 1921],’ says Professor Lahiri

After completing her first PhD in Calcutta, the young Dr Lahiri went to Brown, in the US, to take a second doctorate. From there, she went to teach at UCLA and then to UC Santa Cruz on the other side of the States. She thought perhaps her career would be in the US, but an offer came from the internationally renowned Max Planck Institute for Psycholinguistics – in the Netherlands. It was an offer she could not refuse.

From the Netherlands, she was offered a Chair in General Linguistics at the University of Konstanz in Germany, where she was to live for the next 15 years. Arriving in Oxford 14 years ago, she was asked convert the excellent Committee for Comparative Philology, Linguistics and Phonetics into an independent Faculty, which is now flourishing.

Professor Lahiri admits modestly to speaking quite a few languages, including Bengali, German and English. She has specialised in Germanic languages, ancient and modern, including Gothic, Old English, and Old High German. Her interests continue to span historical traditional linguistics and experimental brain-imaging research. These interests have not changed.

Although she is set to step down next year, Professor Lahiri is looking forward to continuing with her research. There are so many deep questions about language unanswered, and indeed unasked. A whole new vista beckons.

By Sarah Whitebloom