Computer imaging could be the key to unlock the world’s oldest mystery script, says Oxford linguist.

The world’s oldest undeciphered script may soon be cracked at Oxford with the aid of cutting-edge computer imaging technology.

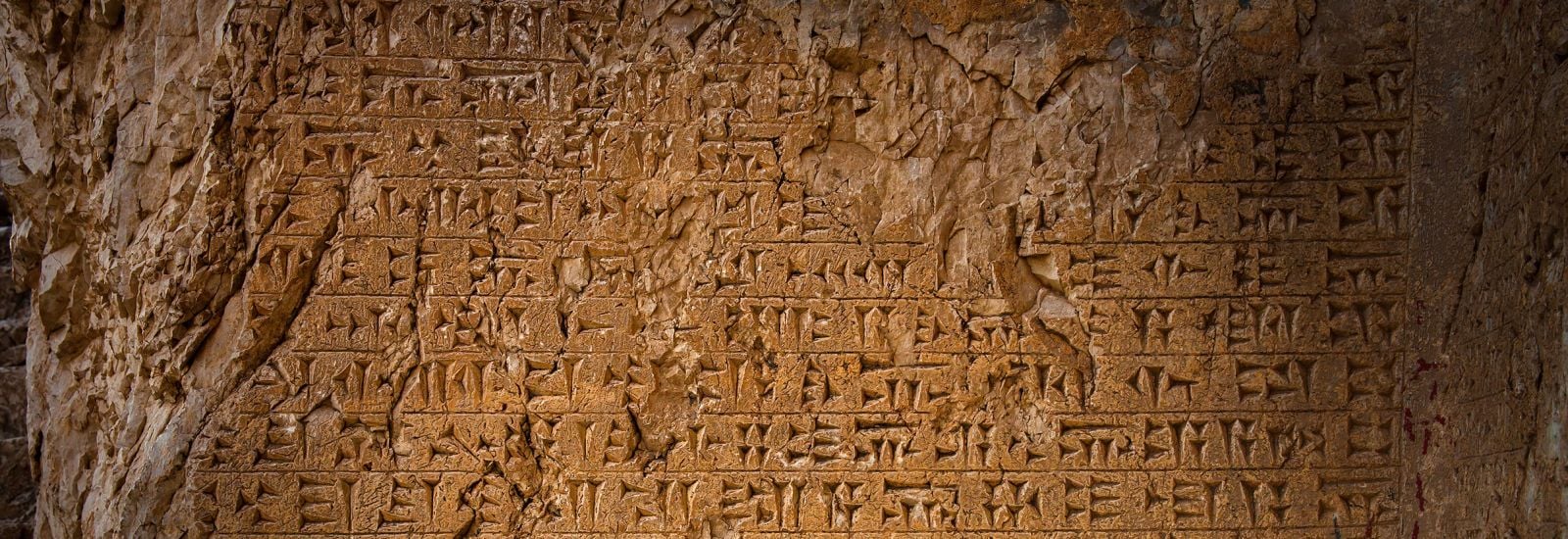

Scholars trying to decode Proto-Elamite have been hampered by having to work from dated copies and photographs, says Jacob Dahl, Professor of Assyriology at Oxford's Oriental Institute. He believes a technique that allows a digital image to be lit from different angles would vastly improve comprehension of cuneiform tablets in general, and help unlock the stubborn secret of Proto-Elamite in particular.

Mesopotamia was the birthplace of writing itself – not to mention metal-smithying, glass-making, building, institutions of war and trade, and other key aspects of civilisation. All this is documented in up to 600,000 surviving tablets in various languages, written between 3,500BC and the last centuries BC. 'From that period, half of human history, we have a staggering amount of ancient original texts on clay tablets – more than Rome, Greece and Egypt combined,' says Dahl, a principal investigator behind the online, open-access Cuneiform Digital Library Initiative. About 350,000 tablets are catalogued by that project. Many are too fragile to transport, while some are inaccessible or in danger of destruction.

Except for the best-preserved tablets, traditional photography cannot capture the text properly. Scribes used a pen-like tool to impress wedge-shaped marks in clay tablets that were often curved. The three-dimensional nature of the texts, complicated by the porous and cracked condition of many tablets, means that photographs just don’t cut the mustard. It raises special challenges to deciphering the Proto-Elamite script, which records an unknown language spoken between 3100 and 2900BC and centred on Susa, present day Shush in western Iran. It is vital to identify which marks are deliberate and which are accidental.

The new technology that Dahl uses, originally developed by T Malzbender from Hewlett-Packard labs in the US and called Reflectance Transformation Imaging (RTI), seeks to replicate the experience of having access to the original object, which can be illuminated from any number of angles with a raking light to cast shadows in high relief.

With the RTI system that Dahl uses, developed by his colleagues at Southampton, the tablet is imaged using 76 separate lights and the resulting data is encoded at pixel level in a single digital image file. Dedicated software then allows researchers to view a model of the tablet where the light can be moved to any possible position, to replicate the effect on computer of holding the original tablet against a strong light source.

Beyond Proto-Elamite, Dahl is currently working with collaborators from the University of Southampton on a new kit to image and digitally unwrap the tiny cylindrical seals once used to print onto clay surfaces. Of the 50,000 in existence, those held by the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford will be the first to be subjected to this new technology.

Dahl says work on Proto-Elamite itself is 'painstakingsly slow' – limited in particular because he is the world’s only full-time professional working on the script with a complete corpus overview. Agreement may be nearing with authorities in Iran to digitise the half of the corpus that remains there. If the corpus were all available using RTI, says Dahl, 'That would make the entire corpus available to anyone who wanted to try their luck.'

Dahl is convinced that understanding the material would be invaluable. 'We stand on the shoulders of giants with our unparallelled success and technological advance,' he says. 'If we didn’t understand from where that came, we would not only be poorer as a society, but we wouldn’t be as efficient at making further progress.'

What makes Oxford so outstanding in this field?

"We exchange information very much across disciplinary boundaries, even between humanities scholars and scientists. Things move very fast in Oxford; we attract very bright students; we have very good study collections and the access to them is very open, with staff eager to engage with the rest of the academic community in trying out new methods. So there's a certain energy of the place that makes these initiatives possible, and a relatively straightforward process of applying for internal funds that can kickstart projects. Oxford is also extremely well-connected internationally, both through alumni and of course our own business projects that span the entire globe. This is an optimal place to push the boundaries always of what you can do."

Associate Professor of Assyriology, Oriental Institute

Co-PI of the Cuneiform Digital Library Initiative

Article written by John Garth (www.johngarth.co.uk)

"To think innovatively about ancient society is to suddenly see connections or causes that you hadn’t thought about before – based, of course, on the correct methodological processes. But you can also be innovative in your methodology.… It’s something that challenges earlier notions of how to do things and why to do things." Jacob Dahl