Features

A statistical analysis of 650 UK spinouts between 2010 and 2021 shows that the university proportion of equity share has a limited effect on multiple fundraising factors including the probability of spinouts raising equity, the amount of funding raised, and the market valuation of a spinout after it has received funding.

The study, released last week by the Saïd Business School at the University of Oxford, provides a UK-wide analysis of UK spinouts where a university owns at least a 1% stake of founding equity.

The results speak for themselves, there are some specific effects but the broad-brush argument, that higher university stakes make spinouts unfundable, is not supported in the data.

Professor Thomas Hellmann

The paper’s lead author, Thomas Hellmann, DP World Professor of Entrepreneurship and Innovation at the Oxford Saïd Business School, said, ‘This often-heated debate about a university’s stake in their spinouts happens in a data vacuum, based on opinion and anecdote. We are addressing this gap by analysing systematic data on the relationship between university stakes and subsequent fundraising outcomes. The results speak for themselves, there are some specific effects but the broad-brush argument, that higher university stakes make spinouts unfundable, is not supported in the data.’

The paper entitled ‘How does equity allocation in university spinouts affect fundraising success? Evidence from the UK’ highlights that the average university equity share is 31% and declining, with the University of Oxford’s equity share at 20%, well below the UK average reported. The finding also suggest that the more resources available to university technology transfer offices to spend on registering IP, the higher the number of spinouts are created.

Oxford University Innovation’s CEO, Matt Perkins, said: ‘We welcome this timely UK-wide study and the rigour of the analysis. University Technology Transfer Offices provide tremendous support to create spinout companies by assessing market potential, registering and covering the costs of intellectual property, advising on investment options, and supporting the creation of management teams. We want to see sustained success for the spinouts created and have supported our founders by reducing the University’ founding equity share to 20%, speeding up the creation of companies and reducing the burden of negotiation.'

We remain committed to foster innovation and entrepreneurship to maximise the global impact of the University’s research and expertise and have delivered this through recently reaching a milestone of 300 companies created.

Matt Perkins, Oxford University Innovation

The analysis highlights that less than five per cent of university spinouts in the UK ever raise more than £25 million. This data suggests the debate should focus less on equity share and more on creating more attractive investment opportunities for UK spin outs to scale up exponentially.

The study shows there is no statistically significant impact of a university’s share on venture capital investment in biomedical and engineering spinouts. It highlights a very minimal negative effect of university share on the probability of raising venture capital in less scientific spinout sectors such as IT.

Professor Chas Bountra, Pro-Vice-Chancellor for Innovation at the University of Oxford said: ‘Oxford remains at the forefront of the UK’s university innovation economy thanks to our researchers and the commercialisation potential of their work. We continue to contribute to the UK’s innovation economy by reinvesting our university returns into funding further research innovation and by aligning our commercialisation approaches with our founders and partners in industry, the investment community, government, and the wider ecosystem.'

Growth of University of Oxford spinouts, 1959 - 2022

Growth of Oxford's spinouts, 1959 - 2022

Growth of Oxford's spinouts, 1959 - 2022At this year's Skoll World Forum Oxford University Innovation (OUI) showcased five social ventures from the University of Oxford changing lives and impacting the environment.

The University’s support for social ventures through OUI started in 2018. Since then 18 social ventures have been created, positively impacting society and making a difference in line with the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals. Discover five social ventures making waves below:

Greater Change: Alleviating homelessness through empowerment

Greater Change is revolutionising how we approach homelessness by providing financial planning support and micro grants to help those in need overcome financial barriers. With over 670 people supported and 80% now in stable housing, this unique approach has proven to be effective in helping those experiencing homelessness get back on their feet. The best part? Greater Change’s approach is scalable and can quickly plug into partners across wide geographies.

Wise Responder: Creating multidimensional wellbeing

Wise Responder is empowering social investments and sustainable human development goals by providing social metrics for financial institutions, investors, companies, and governments to tackle the world’s declared number one goal: United Nations SDG1 – No Poverty. By identifying deprivations at the individual and household levels, including health, education, and living standards, Wise Responder is making a significant impact on poverty reduction. The company is also helping to create sustainability-linked financing and investment options for financial institutions, corporates, and investors eager to make a difference.

Rogue Interrobang: Using creative thinking to solve wicked problems

Rogue Interrobang is helping individuals and organisations unlock their potential and create a better world. With offerings that include creative thinking training, diversity workshops, and coaching, Rogue Interrobang has worked with high-profile clients like the Cabinet Office, HMRC and the Open University. Their products include Mycelium, a card game that promotes creativity, and books “Our Dreams Make Different Shapes” and “Lift,” are just a few examples of how Rogue Interrobang is helping individuals tap into their full potential.

SEREN: Delivering life-saving diagnostic solutions in Africa

SEREN is working to improve access to diagnostic solutions in lower middle-income economies, like Tanzania, where cancer, anaemia and inherited diseases are a major health problem. SEREN provides DNA-based tests for as little as $10, making life-saving diagnostics accessible to those who need it most. Their cloud-based data systems allow for remote analysis and rapid diagnostics by experts so that samples don’t need to be sent abroad and valuable data can be used to further research and the provision of patient solutions.

Nature-Based Insetting: Creating Sustainable Supply Chains for a Healthier Environment

Nature-Based Insetting is helping organisations implement evidence-based targets for mitigating and insetting impacts on climate, biodiversity, and society through nature-based solutions. By enhancing the value and resilience of supply chains, Nature-Based Insetting is making a positive impact on our environment and promoting socially just, nature-positive, and net-zero pledges. With collaborations like Reckitt for biodiversity and net-zero targets, Nature-Based Insetting is helping individual businesses make a significant impact on sustaining a healthy, functioning natural environment and a stable climate system.

The full portfolio of social ventures can be viewed here.

Contact a member of OUI's social ventures team with your questions.

Dr Manuel Anglada Tort. Image credit: University of Oxford.

Dr Manuel Anglada Tort. Image credit: University of Oxford.

Please could you introduce your work?

I am interested in exploring the psychological and cultural foundations of music, and the role they play in human societies and cultural evolution. Music has not evolved from individual brains but instead from being embedded in large cultural processes of multiple social interactions. To understand why music is the way it is, and how we find pleasure in it, we therefore need to consider the collective processes by which music has evolved. To study this, my work combines methods from many different disciplines, including psychology, computer science, musicology, and cultural evolution.

For example, I use singing as a model to study how music evolves when it is transmitted across human generations. Singing is fascinating because it is the most widespread mode of musical expression, practiced by all cultures and ages, even in infants. We developed a novel method to simulate the evolution of music with singing experiments, where sung melodies are passed from one singer to the next, similar to the popular ‘telephone game.’ Using this method, we examine how thousands of musical melodies change and evolve as they are orally transmitted across participants.

What have you found so far?

We found that oral transmission has profound effects on how melodies evolve, shaping initially random sounds into more structured musical systems that increasingly reuse and combine fewer elements, such as certain pitch intervals and simple melodic contours (the sequence of ups and downs in pitch). This ultimately makes the melodies easier to learn and transmit over time. Importantly, the structural features that emerged artificially from our experiments are largely consistent with widespread melodic features found in most musical traditions across the world. This suggests that ‘human transmission biases’ in singing may contribute, at least partly, to the observed cross-cultural commonalities found in many music cultures across the world.

The next stage is to work out which factors are responsible for these ‘transmission biases.’ Our experiments show that physical and cognitive constraints in our capacity to produce and process music are of critical importance. For example, melodies that are hard to sing or remember are systematically less likely to survive the transmission process. We also found that participants’ previous cultural exposure is important. For instance, in a group of US participants, the ‘evolved’ melodies tended to align with certain cultural conventions of Western music, whilst a group of participants from India showed cross-cultural divergences.

Overall, this work is exciting because allows us to study evolutionary processes that are typically hidden or very hard to measure. We are excited to extend this work to study other production modalities, such as speech, as well as to test participants from more diverse musical backgrounds.

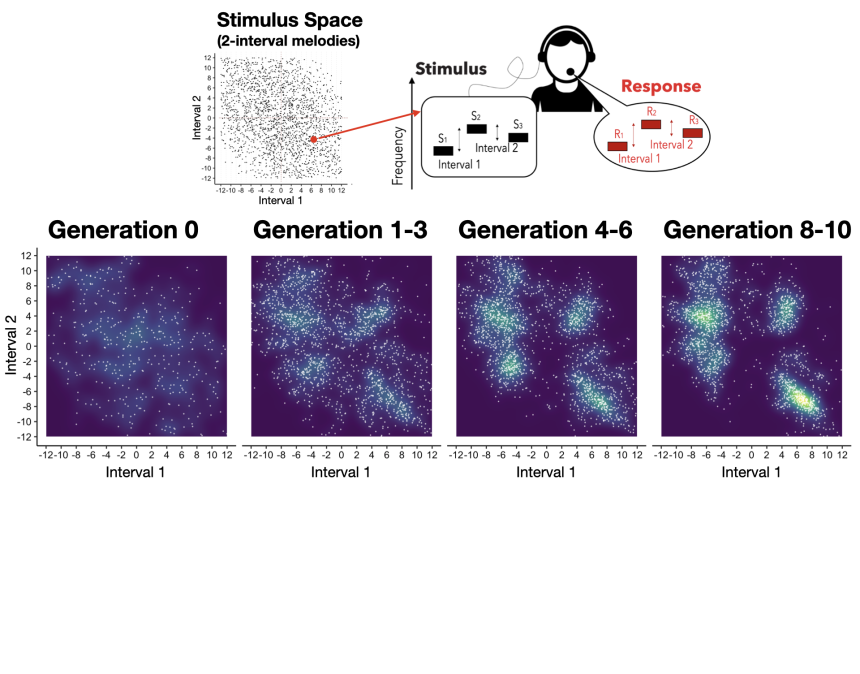

Online iterated singing method, developed by Manuel to study how oral transmission affects the evolution of melodies in songs. Participants hear a sequence of tones generated by a computer and reproduce it by singing back. The vocal reproductions are analysed by a computer and played to the next participant as the input melody. This process is repeated with many parallel transmission chains at the same time, each corresponding to a melody evolving over 10 generations. Image credit: Manuel Anglada Tort.

We talk of the culture of music but essentially, music is culture. Just as we cannot understand culture by only looking at individual brains, we cannot understand music without considering the larger cultural and social processes surrounding it.

For your PhD at the Technical University of Berlin, you studied how behavioural economics can be applied to music cognition. What did you find?

Behavioural economics recognises that human beings do not always think through every decision rationally. For example, we often rely on cognitive heuristics to simplify complex decisions: mental shortcuts that allow us to use information selectively and effectively.

In my PhD, I showed that, when it comes to music decisions and preferences, the context in which music is presented has a very important influence. Our preferences for music will change dramatically depending on the time and day of the week, which activity we do while listening to music, whether we are alone or with others, and what information we know about the artists’ skills and persona. Even small variations on the title of a song can have an important impact on how much people like the music.

In one experiment, we showed that contextual factors can completely change our experience of the same piece of music. We told participants to listen to ‘different’ musical performances of an original piece when in fact they were exposed to the same repeated recording three times. Each time, the recording was accompanied by a different text providing information about the supposed performer, which was manipulated to indicate either low or high prestige of the performer. We found that most participants (75%) believed that they had heard different musical performances. Interestingly, participants evaluated identical recordings more positively in terms of liking and music quality when they thought the music was performed by a professional musician rather than a less-skilled musician. This suggests that when we judge music, we rely on cognitive biases and heuristics that do not always depend on what we actually hear.

The results of our studies suggest that when we judge music, we rely on cognitive biases and heuristics that do not always depend on what we actually hear.

You have also worked as a science consultant for an audio branding firm. What exactly does audio branding involve?

Audio branding is where brands translate their identity and values into audible elements that are then repeated in their advertisements or used within their products. As we are increasingly saturated with visual information, companies are showing a growing interest in using audio branding to reach target audiences. For example, repeated catchy melodies of three to five notes can be highly effective in making people recognise a brand or product, such as the iconic audio logos of McDonald’s or Netflix. As researchers, we can quantify the effectiveness of different music when paired with certain commercials or brands, for example by measuring the impact of music on consumers’ brand recognition or purchase intention.

In one study, we found that pairing brands with music that can be recognized by the target consumers increased brand choice by 6%. Although this is a small effect, it is quite remarkable given that using music is relatively easy and cheap for brands. But the use of advertising music is becoming much more sophisticated with AI and big data. The future of music and advertising is about creating individualised consumer experiences where the same ads and products can be paired with different music targeting the many individual preferences of consumers.

Oral transmission effects on melodies. The entire stimulus space of three-note melodies (two intervals) can be defined along two continuous dimensions, one for each interval in the melody (with each dot representing a melody). At the start of the experiment (Generation 0), hundreds of melodies were randomly sampled from this space. These melodies were then played to participants, who were asked to reproduce them by singing. Over time, oral transmission shaped initially random melodies into more structured and simplified musical systems. By the end of the experiment (Generation 8-10), melodies were concentrated in few locations, displaying a rich structure that is consistent with Western discrete scale systems. Image credit: Manuel Anglada Tort.

Oral transmission effects on melodies. The entire stimulus space of three-note melodies (two intervals) can be defined along two continuous dimensions, one for each interval in the melody (with each dot representing a melody). At the start of the experiment (Generation 0), hundreds of melodies were randomly sampled from this space. These melodies were then played to participants, who were asked to reproduce them by singing. Over time, oral transmission shaped initially random melodies into more structured and simplified musical systems. By the end of the experiment (Generation 8-10), melodies were concentrated in few locations, displaying a rich structure that is consistent with Western discrete scale systems. Image credit: Manuel Anglada Tort.Music is essentially a psychological phenomenon: our mind has evolved to translate physical qualities of sound into the subjective experience of music.

How did you get in to music psychology?

I have always loved playing and composing music, but my academic career originally started in psycholinguistics and experimental psychology, studying the bilingual brain. I then happened to find out about this small research field in music psychology. For me, music and science seemed the perfect combination, so I applied to Goldsmiths, University of London, to study their MSc in Music, Mind and Brain.

It was revolutionary for me to realise that all the scientific methods I had learnt for experimental psychology could be applied to study music as well; working out how we perceive sound and get pleasure from it, and the many psychological functions that music making and listening have. I remember the lectures on psychoacoustics to be particularly inspiring, where I learnt that music is essentially a psychological phenomenon: our mind has evolved to translate physical qualities of sound into the subjective experience of music. For example, we perceive pitch from the speed at which an object vibrates: the faster the vibration, the higher our perception of pitch. By combining different sets of music pitches, we can in theory create infinite music patterns. Some of these patterns will become popular in a given population, whereas others will die out.

I feel very fortunate that this work is a fusion of three key interests of mine: science, music and culture.

What plans do you have for the Music, Culture, and Cognition group in the near future?

I am excited about the potential of this group, and I feel very fortunate to have an incredible network of international collaborators with expertise in music cognition and cultural evolution. The idea is to continue to perform cutting-edge research on the intersection between music, culture, and cognitive science here at the University of Oxford. This will include continuing our experiments to simulate cultural evolution (such as the singing transmission study) and extending these methods to also study more complex cultural phenomena. For example, to study how the evolution of musical structures may depend on selection pressures (e.g. composers vs critics vs consumers) or underlying population structures, such as social networks and their different patterns of connectivity.

Another exciting line of research is on the topic of cultural globalization and popularity dynamics: exploring how songs spread across the world and what determines whether a song will become a global hit or not (also known as ‘Hit Song Science’). Traditionally, people have attempted to predict music success based only on the content of the music: its harmony, timbre, or rhythm. But studies have repeatedly failed to predict musical success based on musical features alone. I believe that the distribution network by which music spreads within and across countries may help solve this puzzle. So, we are investigating ways to measure and quantify this underlying network of music diffusion and its impact on cultural globalization.

You arrived here less than two months ago – what do you make of Oxford so far?

Oxford is an incredible place and I feel very privileged to be here. Unlike ‘campus’ universities, you feel that the whole city itself is the university; you sense it all around you. The musical scene is excellent (which is important to me) and more generally, it feels that this is a place where anything you might want to do is possible – from life drawing, to dancing, to playing any kind of instrument. I have already found a group of friends to go rock climbing with and recently got into bird watching for the first time. I have also fallen in love a bit with the English pub culture. Coming from Spain, I had never seen anything like them before, and am fascinated by how they are all so different and have so much history. I am looking forward to exploring all the ones in Oxford over time!

You can read Dr Manuel Anglada Tort's latest research paper 'Large-scale iterated singing experiments reveal oral transmission mechanisms underlying music evolution' in the journal Current Biology.

In the video below, Manuel Anglada Tort describes his work to study the effect of oral transmission on music evolution using online singing experiments, in an event for the Oxford Seminar in the Psychology of Music.

Tatjana Gibbons, a DPhil student at Oxford’s Nuffield Department of Women's & Reproductive Health, talks about research to develop a new 20-minute diagnostic test for endometriosis.

Around one in ten women will develop some form of endometriosis in their lives, a disease that affects more than 190 million women worldwide.

Yet despite its common occurrence, it typically takes eight years for a diagnosis – a figure that has shown no sign of improving in the past decade. The problem is that it typically involves several visits to the GP and hospital referrals, multiple scans and often surgery to diagnose.

Not only does this leave patients suffering for a significant period of time, but it can also require unpleasant and invasive procedures.

Aside from the pain, discomfort and worry about an ongoing undiagnosed condition, an important issue is its effect on fertility when left unchecked. A national questionnaire we conducted with over 1000 respondents with confirmed or suspected endometriosis found that 88% of respondents had experienced a delay in diagnosis, and 72% felt that an earlier diagnosis would have changed their life choices with regard to decisions such as fertility planning. With earlier diagnosis, it is possible to treat both the pain and discomfort as well as to begin to consider fertility options such as freezing eggs for the future.

The problem with diagnosing endometriosis is that small lesions in the pelvis are not detected on ultrasound and often need surgery to detect. This is why we are assessing alternative ways of looking inside the body without being invasive.

Our research group is conducting the DETECT (Detecting Endometriosis expressed inTEgrins using teChneTium-99m) imaging study, to investigate whether an experimental image marker (⁹⁹ᵐTc-maraciclatide) that binds to areas of inflammation can be used to visualise endometriosis using a 20-minute scan. In endometriosis, small parts of the lining of the uterus – the endometrium – are found in the fallopian tubes, ovaries or in the pelvis (for example, attached to bowel). The presence of the endometrium outside of the uterus leads to inflammation in the pelvis, which this test will aim to highlight.

If this is successful, it will give us a fast and effective way to identify any case of endometriosis, as well as assessing how serious the patient’s individual condition is and may even be able to distinguish between old and new disease.

Professor Christian Becker, who is Co-Director of the Endometriosis CaRe Centre in Oxford together with Professor Krina Zondervan, Head of Department at the Nuffield Department of Women’s and Reproductive Health, University of Oxford, will lead this initial study on women due to have planned surgery for suspected endometriosis.

Two to seven days before their operation, the participants will be invited for an imaging scan which will compare the suspected locations of disease detected on the scan and in surgery to confirm whether this imaging test matches what is found.

The beauty of this approach is that, if successful, it will provide a quick, painless and affordable option for tens of millions of women worldwide.

To read more about this research project and the partners involved, please visit https://www.wrh.ox.ac.uk/news/new-imaging-study-could-make-diagnosing-endometriosis-quicker-more-accurate-and-reduce-the-need-for-invasive-surgery

The study is being carried out in partnership with Serac Healthcare, a UK-based developer of breakthrough imaging technology.

Professor Sarosh Irani of the Nuffield Department of Clinical Neurosciences

Today – Wednesday, 22 February – is World Encephalitis Day.

Encephalitis is a brain condition which I have encountered many times throughout my career, witnessing first-hand the devastating impact that it can have on patients and their family and friends.

My team in Oxford work to improve the diagnosis, treatment and after-care for patients with autoimmune forms of encephalitis. Discoveries to improve patient care is what drives everyone in my research group and clinic, and is what led me to become a member of the Encephalitis Society’s Scientific Advisory Panel.

Our work has focused on the autoimmune forms of encephalitis, where one’s own immune system attacks the brain in error, leading to brain swelling. We work hard, with our patients and their carers, to better understand diagnosis, the underlying cause of the diseases and patient outcomes. We have over 150 publications in this area, and aim to produce many more over the next few years.

Another key aspect of my work is improving awareness of encephalitis among the general public and fellow healthcare professionals in the hope that it can eventually lead to a quicker pathway for patients to get the care they need.

Shockingly, a YouGov poll commissioned by the Encephalitis Society has found that around 8 out of 10 people do not know what encephalitis is, which is why I would like you to spare a few moments and read the following facts:

1. Encephalitis is an inflammation of the brain

2. It is caused by an infection or through the immune system attacking the brain in error

3. Anyone can be affected by encephalitis, irrespective of age, gender or ethnicity

4. It can have a high death rate and survivors might be left with an acquired brain injury and life-changing consequences

5. In some cases, encephalitis can impact mental health, causing difficult to deal with emotions and behaviours, and can lead to thoughts of self-harm and even suicide

To add our support to this very important day on the calendar, my colleagues and I have been wearing red today as part of the Encephalitis Society’s #Red4WED social media campaign and, this evening, I am delighted to say that the University of Oxford’s Ashmolean Museum will be among 200 global landmarks, including Niagara Falls, Piccadilly Lights, and the CN Tower in Toronto, lighting up red for World Encephalitis Day.

Finally, if you are a social media user, I urge you to take some time this evening and search for the hashtags #WorldEncephalitisDay, #Red4WED and #encephalitis for a wonderful example of what can be achieved when a community comes together with a special goal in mind – to shine a light on encephalitis.

For more information, visit www.worldencephalitisday.org

- ‹ previous

- 6 of 247

- next ›

World Malaria Day 2024: an interview with Professor Philippe Guerin

World Malaria Day 2024: an interview with Professor Philippe Guerin From health policies to clinical practice, research on mental and brain health influences many areas of public life

From health policies to clinical practice, research on mental and brain health influences many areas of public life From research to action: How the Young Lives project is helping to protect girls from child marriage

From research to action: How the Young Lives project is helping to protect girls from child marriage  Can we truly align AI with human values? - Q&A with Brian Christian

Can we truly align AI with human values? - Q&A with Brian Christian  Entering the quantum era

Entering the quantum era Can AI be a force for inclusion?

Can AI be a force for inclusion? AI, automation in the home and its impact on women

AI, automation in the home and its impact on women Inside an Oxford tutorial at the Museum of Natural History

Inside an Oxford tutorial at the Museum of Natural History  Oxford spinout Brainomix is revolutionising stroke care through AI

Oxford spinout Brainomix is revolutionising stroke care through AI Oxford’s first Astrophoria Foundation Year students share their experiences

Oxford’s first Astrophoria Foundation Year students share their experiences