Features

Rainforests are amazing places - great biodiverse ecosystems and carbon sinks. But, as a million nature programmes have shown, they are also full of things that could kill you: insects as big as your fist, some of the deadliest snakes alive, even the frogs can be nasty. Not unreasonably, this might well deter many people from venturing into these great forests – but not Oxford professor Yadvinder Malhi. He admits, he likes that sort of thing...a lot. It is not just the biodiversity which attracts the professor of Ecosystem Science, but the challenging nature of doing research there, the fact we still know so little about them and the major role rainforests have to play in our climate.

A million nature programmes have shown, rainforests are full of things that could kill you...Not unreasonably, this might well deter many people from venturing into these great forests – but not Oxford professor Yadvinder Malhi. He admits, he likes that sort of thing...a lot

Until the pandemic, Professor Malhi had spent years in and around tropical rainforests, visiting field research sites most years. He took his young family on holiday to one dense forest deep in Borneo and only went to the beach, reluctantly, after his son protested at the idea of even more time in the rainforest. This year, though, he has been a stay-at-home academic, with the most challenging environment being Oxford and the University’s Wytham Woods (actually a very interesting place to study, says the professor).

It is a far cry from where the genial professor grew up: darkest Essex. Although, when he was around six, the young Yadvinder’s parents sent him to live with his grandparents in the Punjab for a year – so he would understand his Indian roots. Life could not have been more different (and more challenging), but Yadvinder discovered an intense life in full colour surrounded by warm, welcoming people – and his love affair with tough places and nature began.

‘I saw the world open up for me,’ he says. ‘It made me want to explore the whole world.’

He recalls how his cousins would bring him local birds and animals to inspect, catching parrots in basket traps, so the budding young scientist could inspect them. After a year, he returned to monochrome Essex, more interested than ever in the scientific world, and told his incredulous classmates about one discovery, ‘There are more brown people in the world than white.’

'They did not believe me,' he laughs. Yadvinder's keen interest and scientific ability, took him from his local school to Cambridge in the late 1980s, to study Physics.

‘I wanted to study astronomy,’ he says. Awareness of the issue of climate change was in its infancy, but he was beginning to think that maybe environmental science, rather than the stars, was for him.

‘There is a tradition of physicists going into biology,’ he adds. ‘I’ve learned a lot in the process.’

Going to Edinburgh after his doctorate, the young researcher took his first big step into the natural world, with a study visit to Brazil. He learnt Portuguese (though his samba didn’t improve much) while waiting for his equipment to clear customs (it took three months). But the main point was to work in the rainforest.

‘We worked on a scaffolding tower in the middle of the Amazon,’ he says, reminiscing fondly. ‘We measured the rain, air and water....this was the first time I had been in a rainforest. I loved it all, the bugs, the big skies, the multitude of living things, everything.’

He adds, ‘There was rainforest for a 1,000 miles in every direction. It’s a continent-sized forest. To see such vast nature and to feel so small - it was transformative.’

There was rainforest for a 1,000 miles in every direction [on his first trip to the Amazon]. It’s a continent-sized forest. To see such vast nature and to feel so small - it was transformative

Professor Yadvinder Malhi

Perhaps with memories of his days as a boy naturalist, he says, ‘There was so much to learn. I was more and more fascinated by ecology.’

He was eager to learn more about ecology – while bringing his physicist’s mindset to the research. Professor Malhi worked largely in Brazil until the early 2000s, when he was invited to look at the potential to do research Peru. He loved that too, ‘I looked at the Andes, it was fantastic. We spent a few weeks, trekking ancient Inca trails.’

On the slopes of the Andes, working with local and international partners, he helped establish a ‘vertical science laboratory’, stretching from the steaming lowland rainforest to the high treeline of the cloud forest, four km up in the atmosphere.

Full of things that could kill you: Yadvinder smiles at the memory of days in the rainforest.

Full of things that could kill you: Yadvinder smiles at the memory of days in the rainforest. He beams as he remembers with evident happy memories, ‘We put study sites all up the sides of the mountains to understand how climate affected tropical forests, and moved plants and soils up and down the mountains [to look at the environment at different levels].’

The same method has now been adopted in other forests from Brazil to Borneo.

‘I was trying to look at the forest as a physicist would, as a system,’ he says.

In 2004, he arrived in Oxford, with a Royal Society fellowship. His work could continue, but he was based, for part of the year anyway, in the city of dreaming spires. Cycling home one rainy Michaelmas day after an intense few weeks of teaching, he missed the outdoors, the forest, the sun. On arriving home, he discovered his wife had been offered an overseas posting – Ghana. He did not need to be asked twice.

Cycling home one rainy Michaelmas day...[in Oxford] he missed the outdoors, the forest, the sun. On arriving home, he discovered his wife had been offered an overseas posting – Ghana. He did not need to be asked twice

‘We went to Ghana for three years,’ he says. ‘I was a stay-at-home father for much of the time, but I used it as a chance to get to understand the forests and people of this continent that was so new to me.’

He adds, enthusiastically, ‘Africa has an unjustified reputation to be really difficult to work in, but once you know people and build local friendships, it can be great and immensely rewarding. I have developed some wonderful long term friendships and working relationships there, and now over half my work is in Africa’

Since the creation of the vertical lab in the Andes, a key part of Professor Malhi’s work has been researching, with partners on the ground, the metabolism of the forest. It is critical work – finding out what is in the rainforest and what is happening – and it is varied from country to country and even within the same forest.

‘We were doing our own research but we realised a global understanding of rainforests was needed, which is where the Global Ecosystems Network (GEM) came in,’ he says.

‘We can see how events, such as El Niño, can lead to carbon pouring into the atmosphere [as the rainforest turns from carbon sink to carbon producer]...half of our plots [study sites] in a key part of the Amazon caught fire and we have been tracking them to see how they recover. These long-term ecological observations are like an ecological weather station, giving us insights into how the forests were and early warning of how they might be changing.’

We can see how events, such as El Niño, can lead to carbon pouring into the atmosphere [as the rainforest turns from carbon sink to carbon producer]...These long-term ecological observations are like an ecological weather station, giving us insights into how the forests might be changing

Professor Malhi

His scientific interest is clearly to the fore as Professor Malhi talks about major weather events, which are becoming more common, potentially having the capacity to turn a massive carbon sink into a carbon producer. The consequences for climate change would be severe. He maintains nature and the rainforest will play a huge role in the battle against climate change, ‘Restoring the rainforest and nature can’t solve climate change, but it can make a substantial and real contribution, while bringing all the many other benefits of a thriving natural world.’

Talking about the new Oxford Martin School Programme in Biodiversity and Society, his particular focus is on better connecting the university to nature restoration projects and plans recovery in the surrounding landscapes of Oxfordshire.

‘We need to do something here locally...the UK’s biodiversity is in a poor state and there’s a lot of potential and new political will to make things better. The experience of lockdown really brought home the importance of local nature. Biodiversity is no longer just thought of as something just nice to have – it’s seen as essential, bringing lots of benefits such as human health and wellbeing, flood control and air quality.’

Restoring the rainforest and nature can’t solve climate change, but it can make a substantial and real contribution, while bringing all the many other benefits of a thriving natural world

Professor Malhi

Professor Malhi is hopeful about the future of the natural world, ‘This is an exciting time. We’re going to see serious efforts to maintain and restore biodiversity...there’s a very positive agenda. It’s no longer about just stopping bad things happening, but about making good things happen.’

And his enthusiasm for research and hard-to-reach places is evident, ‘It’s amazing what you can learn from the countries we work in, from the people who live and work there every day, and from the amazing variety of tropical nature.’

As for him, the Essex boy cannot wait for the pandemic to be over, so that he can head back to where the wild things are, for the sake of science, ‘As a scientist, it’s really important to have a passion, a passion for finding things out – that’s much more important than revising for exams.’

Launching two major pieces of work about meat eating at the same time of year might not sound like ideal timing. But COVID-19 meant that LEAP, Oxford’s Livestock, Environment and People project, was faced with doing just that - launching two projects not only in the same week but on the same day in May. But, actually, it works, according to Lucy Yates, LEAP’s Public Engagement Coordinator.

‘What an opportunity to reach different audiences at the same time,’ she said. ‘By inviting them to Oxford’s Natural History Museum to see Meat the Future and going out to meet a broad range of people around the country with our touring installation, Meat Your Persona.’

LEAP research aims to contribute to an evidence-based discussion on the future of meat production and consumption: how frequently it should be eaten and its environmental and health impact. Some key research findings include:

- Even if we cut all fossil fuel emissions immediately, we still would not reach climate change targets without also cutting food emissions.

- Eating high quantities of processed and unprocessed meat is associated with higher risks of colorectal cancer and ischemic heart disease among other diseases.

Meat the Future offers serious food for thought about how the consumption of meat affects our health and the planet.

Meat the Future offers serious food for thought about how the consumption of meat affects our health and the planet. Showcased in striking, engaging displays, visitors to the museum can find out more about LEAP’s research and learn about the impact of meat eating. Displays include stacks of meat, which compare consumption in different countries. Visitors can browse a supermarket fridge, to find out more about ecolabels for foods, and be transported to the South American rainforest – where biodiversity is under acute attack from agriculture. They can also discover the carbon footprint of their own shopping habits in a specially developed digital interactive.

Professor Sir Charles Godfray, Co-Director of LEAP, Oxford Professor of Population Biology, and Director of the Martin School said, ‘With a population likely to peak above nine billion this century, Meat the Future asks how we square our growing demand for meat with the needs of the planet.’

Meat Your Persona, meanwhile, is a touring installation in a bright yellow horsebox, by design consultancy The Liminal Space. Subtitled ‘What you eat and how it can change the world’, it is also aimed at highlighting the impact of meat eating on the environment and the individual. It offers a fun quiz to find your ‘meat persona’ – such as the BLT or the Happy Eater – and there are a host of other interactive activities designed to help you find out more from new recipes to learning more about Leap’s research.

Meat Your Persona will provide us with invaluable insight into the UK's current thinking around meat consumption and, hopefully, encourage individuals to think more deeply about the impact their food choices have on our environment.

The travelling exhibition is designed to speak to diverse audiences about their meat consumption and be fun along the way.

So far, the yellow horse box has visited shopping centres in Cardiff, Leeds and Newcastle. Blackpool and Glasgow are yet to come - along with a return trip to Leeds.

If you cannot see it in person, can take the quiz and find your meat persona at www.meatyourpersona.com.

Susan Jebb, Professor of Diet and Population Health, Co-Director of LEAP, commented, ‘Most people in the UK are unaware of the environmental impact of meat or the health harms caused by eating too much meat. Meat Your Persona will provide us with invaluable insight into the UK's current thinking around meat consumption and, hopefully, encourage individuals to think more deeply about the impact their food choices have on our environment. This is often a difficult conversation to have, however we feel The Liminal Space has created a positive and engaging way to connect the public to our research.’

The response from the public so far has been very encouraging.

One visitor said, ‘Admiration for a brilliantly put together, very informative exhibition. As a result of this exhibit we have decided to cut beef from our diet for the rest of the family.’

A visitor to Meat Your Persona commented, ‘I am inspired by all the recipes. I think giving up meat would be good for my health so I want to try to cut down.’

After a far busier start to 2021 than she could have possibly imagined, Lucy Yates is delighted both projects have launched successfully and is looking forward to a summer of lively engagement and hearing the public’s thoughts on meat eating.

Come to visit Meat the Future at the Oxford Museum of Natural History or catch Meat Your Persona in Leeds, Blackpool, Glasgow or online. If you are interested in reducing your meat consumption, you can also sign up for our cohort study at www.optimisediet.org.

Wellcome generously support both projects.

In spite of everything, many people still underestimate women, in general, and older women, in particular. They have clearly never encountered Kay Davies, the dynamic 70-year-old Oxford geneticist, who is ‘retiring’ after a lifetime’s research (but not really). Just a few minutes immersed in the company of the self-effacing-but-determined Professor Dame, is enough to make anyone exhausted and put paid to stereotypes about women.

Forget about older women being invisible, you could not miss Professor Davies, who arrives promptly for her interview, lovely in a hallmark brightly coloured jacket

Forget about older women being invisible, you could not miss Professor Davies, who arrives promptly for her interview, lovely in a hallmark brightly coloured jacket (more of which later).

But the professor’s story is even more arresting than her striking appearance. Having arrived in Oxford more than 50 years’ ago, Professor Davies has worked with some of the leading medical scientists of the last half century.

She has been tirelessly at the cutting-edge of genetic science; is close to a cure for a devastating genetic condition – and has found time to be a member of the Council of the Medical Research Council, Deputy Chair of the Wellcome Trust and hold a variety of other posts. Professor Davies has been honoured in the UK (a CBE, followed by a DBE in 2008) and in the US (by the American Society of Human Genetics) – oh...and she has a family.

Being a mother makes you well organised,’ laughs Professor Davies, with typical modesty.

That’s true, of course, but there’s well organised and well organised

‘Being a mother makes you well organised,’ she laughs, with typical modesty. That’s true, of course, but there’s well organised and well organised.

‘I am highly organised,’ Professor Davies admits. ‘Having a child makes you more organised. They come first and you arrange things around that. Mothers achieve so much.’

Professor Davies talks passionately of a lifetime spent researching a cure for Duchenne muscular dystrophy, a devastating genetic condition. Duchenne, which strikes boys, affects one in 100,000 globally and sees sufferers confined to a wheelchair, on average, by the age of 12 and rarely surviving their late 20s.

Professor Davies talks passionately of a lifetime spent researching a cure for Duchenne muscular dystrophy, a devastating genetic condition

It has been a labour of true dedication and many many hours in the lab. Having spent decades on genetic research into the condition, Professor Davies hopes there will be a cure within five years. In fact, she says firmly, she is not going to stop until one exists and, listening to her, you just know, she is going to do it – or someone else.

‘It’s been my life,’ she says. ‘I won’t retire until a cure is found.’

Professor Davies was researching genetic treatments when people still thought histone proteins were on the outside of DNA (they’re not) and she has followed the science through to a place where they are now tantalisingly close to major breakthroughs.

It’s been my life...I won’t retire until a cure is found

Professor Kay Davies

It has been a long journey for the clever girl from a state school in Stourbridge, who came to Oxford at the end of the 1960s to study Chemistry (which she did not really like very much) and then switched to Biochemistry.

It had been a very good all-girls school, she says, with an ‘extremely good’ Chemistry teacher. But the young Kay had not been able to take Biology, because, in those days, you needed Latin to go to Oxford and she could not take both.

‘I was never any good at languages,’ she says. ‘But I was good at Maths. I loved problem solving, which is why they probably accepted me.’

Arriving at Somerville, straight out of school, when many people then took the Oxbridge exam and applied post-A levels, she was among the youngest in her year – and one of the very few women. Although she had plenty of drive, she says, although it was a difficult start: she was ‘shy and not very confident’.

‘There were only a few females doing Chemistry,’ she says. ‘I was the only person from a state-funded school and one of the few from a working class background.’

She laughs, ‘I had something of an inferiority complex, although I was able to do the subject. I had drive, though, I probably got that from my mother. She had a lot of drive.’

I learned style from Mary Archer [a tutor at Somerville], but a lot else as well...I learned to be more ambitious and adopt a can-do attitude

Professor Davies

Oxford’s tutorial system helped the young scholar set aside her reserve. She says simply, ‘It was very competitive. But I found I was surrounded by amazing women.’

The then very young Mary Archer was a tutor at Somerville, ‘She was very driven and meticulously dressed, so stylish and intelligent.’

Professor Davies laughs, ‘I learned style from Mary Archer, but a lot else as well.’

‘I learned to be more ambitious and adopt a can-do attitude,’ she says.

Kay Davies: last day in the lab.

Kay Davies: last day in the lab.Oxford was a very different place in those days, she says, clearly full of enthusiasm about the way the university has changed, ‘It’s a lot more collaborative now than in the 70s. There’s such a buzz now...there are links between the medical sciences and other sciences and the whole thing functions much better.’

It is evidently a heart-felt sentiment. One of the key threads in the professor’s career has been her cross-disciplinary work – which began when she swapped Chemistry for Biology and medical sciences. After completing undergraduate degree, Kay took a DPhil in the very new study of the structure of genes. After completing her doctorate, Professor Davies went to Paris where her husband, later an Oxford professor of Chemistry, had a position.

Dr Davies commuted to London to work in a laboratory at St Mary’s hospital – just near Paddington station.

She says. ‘I got off the train at Paddington and went straight into the lab.’

Though still a young researcher, she worked with some of the pioneers of genetic research. At St Mary’s, she worked for Professor Bob Williamson, the distinguished British geneticist. It was ‘so exciting’, she says, but the cross-country commute was a bit much, even for Kay Davies.

Why Duchenne? Because it affects boys, so we could narrow down where we were looking for the gene, says Professor Davies

But finding and isolating the gene has not been simple

It took an intervention from the Nobel Laureate, genetic code specialist Professor Sydney Brenner, to suggest her return to Oxford. He clearly spotted something in her and decided she should be encouraged. In the days before HR, he picked up the phone and called Oxford.

‘He told them I should have a place...So I moved my fellowship to Oxford in 1984,’ she says.

Whilst in London, Professor Davies alighted on Duchenne. Why Duchenne?

‘Because it affects boys, so we could narrow down where we were looking for the gene,’ she says simply. But finding and isolating the gene has not been simple.

It has needed ‘tenacity and patience’, admits Professor Davies.

Kay Davies with, left to right: Ally Potter, Dave Powell and Angela Russell

Kay Davies with, left to right: Ally Potter, Dave Powell and Angela RussellIn the event, the gene was found by others and it was ‘very large in the genome sequence’. Then a breakthrough came when a patient in Birmingham was found – who had just 50% of the gene. He had only just been diagnosed and had lived, although he had a milder version of Duchenne, into middle and then old age.

It offered considerable hope for sufferers – if only they could remove part of the gene, replicating the man’s variation. Since then, others have come forward with similar mild symptoms, says Professor Davies, who has become close to many families and charities involved in the debilitating condition.

It needs more screening of molecules for our approach to therapy...We screen a lot of molecules with the help of Angela Russell’s group in Chemistry. And we might end up curing those boys

Professor Davies

‘As a team, we’re very committed,’ she says.

They have to be. Finding a way to change the gene, for those with full-blown Duchenne was never going to be easy. Sufferers are living longer now, thanks to better treatments, but few live to see their 30th birthday.

‘It needs more screening of molecules for our approach to therapy,’ she says. ‘We screen a lot of molecules with the help of Angela Russell’s group in Chemistry. And we might end up curing those boys.’

The gene therapy treatment could also be potentially used to treat other forms of Muscular Dystrophy, Professor Davies says with real passion.

And that’s the key, she says, Passion, ‘This isn’t work...you have to do what you’re passionate about and it will work out. And don’t feel bitter when people knock you back.’

It’s an important thought because, on many occasions during her career, she has been the only woman in a room of dark-suited men. Professor Davies laughs as she says she was occasionally mistaken for a tea lady, ‘You can’t feel bitter about it, that’s why I buy bright jackets. No one mistakes me for a tea lady anymore.’

When disasters such as earthquakes happen, governments and humanitarian organisations need to rapidly allocate aid resources to facilitate recovery, minimise the number of people displaced and reduce the long-term effects. This is a complex task that needs be undertaken in a very short space of time, with potentially serious consequences if not done well.

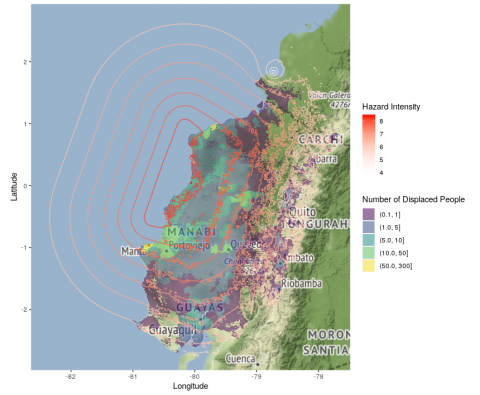

Being able to predict more accurately where people go in the wake of a disaster could be transformative for disaster management: it allows those coordinating the response to ensure shelters are placed in the best locations for the right number of people. Researchers at Department of Statistics, University of Oxford, in collaboration with the Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre (IDMC), have developed an open source software package to estimate displaced populations post-disaster, currently with a focus on earthquakes and cyclones. The software tool has been developed by Dr Hamish Patten and Prof David Steinsaltz, who form part of the department’s bio-demography group. The project, funded by the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council Impact Acceleration Account (EPSRC-IAA) grant, has recently been published with the Global Report on Internal Displacement (GRID) 2021.

The research involved building an open source statistical software product consisting of two components:

· a back-end system which combines the data, model and state-of-the-art statistical methods into a predictive tool, learning from a broad range of historical events in order to make well-informed and accurate predictions of displacement post-disaster.

· a front-end system that interactively visualises the data and predictions, to allow a detailed exploration of important disaster information.

In a comparison of predictions against past displacement figures for over one-hundred earthquakes in 38 different countries around the world, the tool accurately predicted the total displaced population at least ten times more accurately than world leading risk models produced by the United States Geological Survey (USGS) and the Global Disaster Alerting Coordination System (GDACS). The predictions have also enabled a mapping of how the

displaced population is expected to be spatially distributed, which can be used to identify displacement ‘hotspots’ in order to allocate resources more effectively.

By coupling the software with mobile phone data-based displacement estimates provided by organisations such as Flowminder or Facebook Data for Good, we were able to produce a detailed mapping of the returned and displaced populations over time, something that has never been done before. The choice of emergency shelter locations and capacities can also be optimised with the software: given a list of potential shelter locations and capacities, the software package will produce the optimal choice of shelters. This is based on minimising the driving time between displaced populations to each potential shelter location, whilst also considering the finite capacity of each shelter.

The tool is being integrated into the risk models for IDMC, and discussions are also underway to integrate the tool into the risk models used by the International Federation of the Red Cross (IFRC). This research could have a huge impact on aid and resource allocation post-disaster.

Dr Hamish Patten, Research Associate at the Department of Statistics, said: 'Working on predicting disaster-related displacement has been a very stimulating challenge, having to bridge between academia and industry to produce a neat and polished software product for the humanitarian sector, in only six-months. The success of the project was to recognise that many recently-emerged datasets and data sources that can be used to validate risk models have been, until now, almost entirely unused.'

Dr Friederike Otto could not be more self-effacing and pleasant, answering obvious questions politely with patience and apparent interest. And yet the young Oxford professor of climate research is frankly...terrifying. It’s not her, she could not be nicer; it’s what she says. Over the last handful of years, major advances have meant that what were concerns over the impact on climate change, are understood realities. And, she says, it is costing thousands, perhaps millions, of deaths globally every single year.

What were concerns over the impact on climate change, are understood realities – and, says Dr Friederike Otto, it is costing thousands, perhaps millions, of deaths globally every single year

A six-year-old YouTube video of Fredi, as she is universally known, shows a fresh-faced postgraduate researcher telling an audience that deadly extreme weather events may be linked to climate change. Today, she may still be fresh faced, but there is no ‘may’ about it.

Thanks to advances in weather observations and computer modelling-based research by Dr Otto and her team, they now have the data. Previously, climate predictions tended to be based on one model. Now, she and her team use hundreds, thousands of simulations of models - using supercomputers and individuals who lend their processing power. The use of very different models, high-quality observations and experience of many studies has led to her saying with certainty that climate change is behind more than one-in-three deaths from heat. She says, ‘Climate change makes hot extreme events [such as heatwaves in Europe] 100 times more likely.’

‘And we’re not talking about a bit of nice weather either,’ says Dr Otto. ‘The last heatwave in the UK caused 2,500 excess deaths.’

Climate change makes hot extreme events [such as heatwaves in Europe] 100 times more likely...And we’re not talking about a bit of nice weather either. The last heatwave in the UK caused 2,500 excess deaths

Dr Friederike Otto

Two thousand five hundred deaths...from heat in this country. Imagine how many more people are affected internationally; in hot countries - where extreme events are not even recorded. But how does she know that the increased numbers of extreme events are anything to do with climate change?

‘Using multiple computer models, we compare weather under current climate conditions with a hypothetical world without industrialisation. It’s our world, but without greenhouse gas. We see 1.2º global warming – half of which can be seen in the last few decades....the question is never whether this is caused by climate change, yes or no...There are more frequent extreme events now but heatwaves are the game changer...with all other extreme events, such as flooding, there might be some casualties, but with heatwaves there are always deaths.’

In a typically terrifying aside, Dr Otto says quietly, ‘There are no figures for many parts of the world. We don’t have the global excess mortality data, but 37% of deaths from heatwaves over the last 30 years have been caused by climate change. And that is a conservative estimate.’

There are more frequent extreme events now, but heatwaves are the game changer...with heatwaves there are always deaths

Dr Friederike Otto

She adds, ‘We will get hotter. Heatwaves are a huge problem and we don’t take them seriously enough....awareness is still very limited compared with flood risk.’

Dr Otto and her team are working at the forefront of climate science and she is highly sought-after for comments on every weather event. Earlier this month, she was quoted in media everywhere, talking about the impact of climate change on the French grape harvest [not good] and more recently she has been sought for comments about the heatwave currently affecting the north-west coast of North America. Dr Otto has also issued warnings about the lack of tracking of extreme heat events in Africa [really bad] and talked about the climate-linked cost of Hurricane Harvey [huge].

She is all-too-aware of the international politicisation of concerns over climate, ‘It’s a left/right issue, which is not helping.’

Dr Otto maintains, ‘It’s better in the UK, not so polarised...but global net zero goals will only work if all countries act.'

Five-year-old Fredi.

Five-year-old Fredi.'I hated school,’ says Dr Otto. ‘I tried to be there are little as possible.’

But, because of the German education system, and her poor school record, Dr Otto was not able to apply to study such a ‘popular’ subject as History at university. And she was obliged to take either Physics or Engineering – the least popular subjects.

Arriving at Potsdam University, she studied Physics – and was originally very interested in quantum theory. Nevertheless, she also took the only option in climate, ‘basically meteorology not climate change,’ and did not find it very interesting at all. She stuck with quantum physics and also started studying philosophy.

She left Potsdam to take a PhD at a nearby university in Berlin. Increasingly, her interest was captured by the philosophy of science – what it means to be a scientist and what it is that makes science science. And this still underpins her work today, she says.

‘We ask if an event [a flood] is caused by climate change – does this really mean looking at the change in one day’s rainfall or actually the management of rivers...there is always a trade-off. We don’t have observations of all of reality, but these questions are not asked in climate science,’ she says.

Dr Otto is clearly determined to bring attention to the damage wrought by climate change in terms of extreme events. And she is excited by the research into climate finance and net zero pledges (from countries, business and organisation). Both are essential, she says, in the battle to reduce the deadly impacts of climate change. But the scientist is sanguine about whether the pledges will turn into reality, ‘They’ve talked the talk now let’s see them walk the walk.’

One of her students, has been following attempts to bring climate change claims against companies and governments through the courts. The impact could be enormous, says Dr Otto, who talks positively about the prospect of litigation forcing bodies into honouring their climate change pledges, ‘If countries are forced to act and show that they can transform, others will follow.’

She maintains, ‘The legal route will not be the only one, to solve problems. But there could be a ripple effect, [after a court ruling] and governments will do more...But it is especially important for companies to show they are doing something...and a lot of companies have more power than nation states.’

Big national polluters may not care about court rulings or international pressure, says Dr Otto, but ‘we need global net zero not just the UK’ and they do care about ‘money and global markets’

Big national polluters may not care about court rulings or international pressure, says Dr Otto, but ‘we need global net zero not just in the UK’ and they do care about ‘money and global markets’.

She points out, ‘If the European market has strict regulations for importing goods with carbon content, this could be an important factor...and finance is another. Right now, central banks are looking at climate risk.’

It is 10 years, to the day, since the young Dr Otto came to Oxford as a post-doctoral researcher without an employment contract. Now, she is Associate Director of the Environmental Change Institute and Associate Professor of the Climate Research Programme. And she insists, Oxford is ‘a fantastic place to work’.

‘You meet all sorts of people who work here and who come here. And from day one I had the absolute freedom to research what I found interesting as long as I could find the funding.’

People thought I was a weirdo doing something that scientists shouldn’t...a lot of people want to work with me now

Dr Friederike Otto

She talks warmly of her own graduate students, about whose research she is wholly supportive and enthusiastic, ‘Freedom has benefits and everyone here tries to help and support you, especially the admin staff. It’s completely different from universities elsewhere.’

Reflecting on her journey and the rapid development of climate change science, Dr Otto says, ‘People thought I was a weirdo doing something that scientists shouldn’t...a lot of people want to work with me now.’

- ‹ previous

- 16 of 247

- next ›

From research to action: How the Young Lives project is helping to protect girls from child marriage

From research to action: How the Young Lives project is helping to protect girls from child marriage  Can we truly align AI with human values? - Q&A with Brian Christian

Can we truly align AI with human values? - Q&A with Brian Christian  Entering the quantum era

Entering the quantum era Can AI be a force for inclusion?

Can AI be a force for inclusion? AI, automation in the home and its impact on women

AI, automation in the home and its impact on women Inside an Oxford tutorial at the Museum of Natural History

Inside an Oxford tutorial at the Museum of Natural History  Oxford spinout Brainomix is revolutionising stroke care through AI

Oxford spinout Brainomix is revolutionising stroke care through AI Oxford’s first Astrophoria Foundation Year students share their experiences

Oxford’s first Astrophoria Foundation Year students share their experiences DPhil student, Frankco Harris, reflects on his unique journey to Oxford and future plans

DPhil student, Frankco Harris, reflects on his unique journey to Oxford and future plans Oxford undergraduates reflect on their first term

Oxford undergraduates reflect on their first term