Features

Using chemistry to help reach sustainability goals is becoming an increasingly attractive research area. From solving global plastic pollution to improving the performance of rechargeable batteries found in electric cars, ‘green chemistry’ is a truly promising topic.

This article was researched and written by Isabel Williams, a former Masters Student at Oxford University’s Department of Biology.

Tackling the plastic pollution problem

Synthetic plastics do not break down easily, causing them to be a major pollutant in natural environments. Image credit: mbala mbala merlin/ Getty Images.

Synthetic plastics do not break down easily, causing them to be a major pollutant in natural environments. Image credit: mbala mbala merlin/ Getty Images.But why is plastic such a problematic material? To find out why and to begin to tackle these problems, one needs to look at the material’s chemistry.

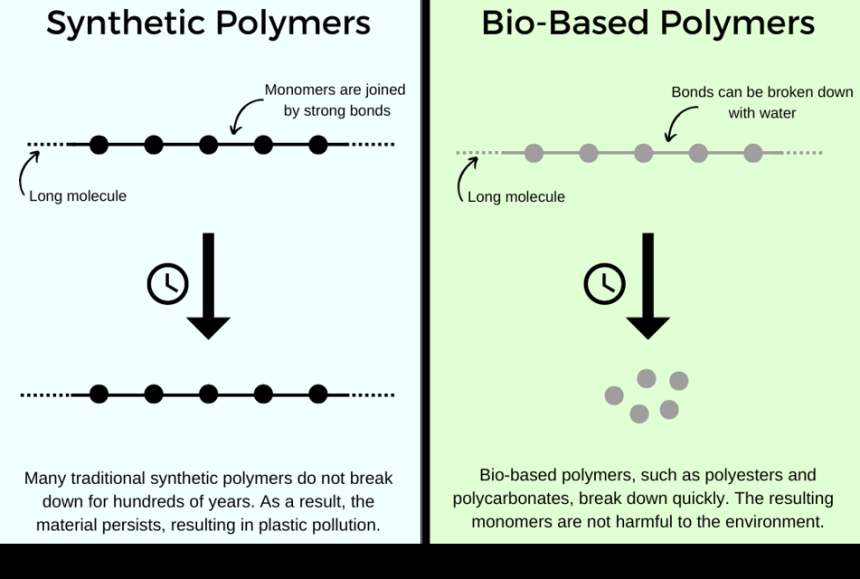

Plastics are made from synthetic ‘polymers’. Polymers are made from small molecular building blocks, called ‘monomers’, forming a large molecule resembling beads on a string. In plastics, these monomers are usually derived from non-renewable sources such as petrochemicals, making the production of plastic polymers highly unsustainable since they rely on fossil fuels. Additionally, due to the strong bonds between their monomers, synthetic polymers can persist and pollute the environment for hundreds of years before breaking down.

The solution: replacing plastics with ‘greener’ polymers

Dr Matilde Concilio (left) and Dr Gregory Sulley (right). Photo credit: Dr Gregory Sulley

Dr Matilde Concilio (left) and Dr Gregory Sulley (right). Photo credit: Dr Gregory SulleyResearchers at the University of Oxford’s Department of Chemistry are utilising a green chemistry approach to tackle plastic pollution. The aim? To phase out existing polymers and plastics and replace them with greener, more sustainable alternatives.

One avenue being explored is the production of polymers from renewable, bio-derived materials, rather than petrochemicals. Dr Matilde Concilio, a Postdoctoral Research Associate in Professor Charlotte Williams’ laboratory, works on making bio-derived polymers from commercially available resources. By using chemicals already commercialised, safety-checked, and approved, the hope is that any products or processes developed in this way will be swiftly accepted and adopted by industry. With bio-derived plastics accounting for only 1.5% of global plastic production in 2021, there is enormous potential for these materials to upscale and ultimately replace their less-sustainable competitors.

I’m convinced that polymers are the future, but only if you do it in a sustainable way.

Dr Matilde Concilio, Department of Chemistry

Dr Concilio’s bio-derived polymers are not only made from renewable sources but are also more sustainable from a processing standpoint. Usually, monomers need to be purified many times to achieve a high-quality final product. This is both energetically costly and expensive.

‘So, to make it more sustainable, what I’m trying to do is use monomers that don’t need to be purified’ Dr Concilio explains. This way, less energy, time, and money are spent on the polymerisation process.

Key to the development and uptake of these new polymers is ensuring that their material properties are as good as, if not better than, current petrochemically-derived options. This is essential if these new materials are to be adopted at scale within plastics industries.

Ultimately, what we want to do is phase out [the current plastics], so that our plastics, which we’re quite heavily reliant on as a society, come from renewable sources.

Dr Gregory Sulley, Department of Chemistry

‘One of the main targets for us is to try and property-match to the incumbent materials,’ says Dr Gregory Sulley, another Postdoctoral Research Associate in Professor Charlotte Williams’ laboratory. ‘Ultimately, what we want to do is phase out [the current plastics], so that our plastics, which we are quite heavily reliant on as a society, come from renewable sources.’

With continued work and collaboration, hopefully, sustainable plastics will go on to replace their more unsustainable alternatives, making plastic pollution a problem of the past. With any luck, the sight of plastic in our landfills, oceans, and beaches will soon be a distant memory.

Tailor-made polymers for energy storage solutions:

Similar green chemistry approaches are being applied to solve problems in energy storage. For instance, rechargeable batteries require their components to be in contact with one another to function. However, this is complicated by the fact that some of the components change volume as the battery is charged and discharged. With these batteries used in electric cars, solar panels, and wind turbines, overcoming this problem is a huge priority to help reach Net Zero emission targets.

So, how do you solve this problem? Enter polymers.

Dr Georgina Gregory. Photo credit: Royal Society.

Dr Georgina Gregory. Photo credit: Royal Society.

This application-driven design is integral to Dr Gregory’s work to improve the design of polymers so that they can overcome the current limitations of rechargeable batteries.

‘The polymer, in some respects, comes in as a way of holding it all together’ Dr Gregory explains. This means the polymer needs to be:

- Adhesive: to stick everything together in the battery;

- Slightly flexible: to accommodate the changes in volume;

- Ionically conductive: the polymer needs to allow ions (electrically-charged atoms) to flow through the battery.

With these three properties in mind, the researchers set out to precisely design a polymer for use in batteries. By specifically selecting building blocks possessing these properties, and utilising their ability to tightly control the polymerisation process, they were able to tailor the product to the problem.

A sustainable solution

The major global problem is replacing the plastics that we currently have. They are in absolutely everything, even things that you don’t even know they’re in.

Dr Georgina Gregory, Department of Chemistry

You would think with these many criteria, sustainability would fall to the back-burner. However, sustainability is still central to Dr Gregory’s tailor-made polymers.

‘I’m always trying to pick building blocks that are bio-based, so polymers won’t have a negative impact at end-of-life.’ Dr Gregory is referring to the fact that bio-derived polymers, in contrast to traditional synthetic polymers, can be quickly broken down using water. Consequently, the material doesn’t remain in the environment for as long, and degrades at a faster rate into smaller, non-toxic parts.

Additionally, the bio-derived polymers lend themselves to chemical recycling. Here, you ‘unzip’, or ‘depolymerise’ the polymer back to the monomers, or original building blocks, then use these monomers to make new polymers. Therefore, the tailor-made, bio-derived polymers don’t contribute to the global issue of plastic pollution.

This ability to produce ‘tailored’ polymers is a special skill, one that is enabling University of Oxford chemists to tackle the crucial engineering challenges that are currently holding back the key technologies we need to achieve Net Zero.

Diagram made by Isabel Williams using Canva.

Diagram made by Isabel Williams using Canva.Taking the hazards out of a hazardous production process

Sometimes, it isn’t so much the end product but the production process that creates environmental problems. Take fluorochemicals, for instance. This group of chemicals have a wide range of important applications – including polymers, agrochemicals, pharmaceuticals, and the lithium-ion batteries in smartphones and electric cars – and had a $21.4 billion global market in 2018. But currently, all fluorochemicals are generated from the toxic and corrosive gas hydrogen fluoride (HF) in a highly energy-intensive process. In addition, even with the best safety precautions, HF spills have occurred numerous times over the last decades, sometimes with fatal accidents and severe environmental impacts.

Thankfully, this may not be the case in the future, thanks to a new, safer approach developed by a team of University of Oxford chemists, alongside colleagues in Oxford spin-out FluoRok, University College London, and Colorado State University. The innovative method takes inspiration from the natural biomineralization process that forms teeth and bones.

Normally, HF itself is produced by reacting a crystalline mineral called fluorspar (CaF2) with sulfuric acid under harsh conditions, before it is used to make fluorochemicals. In the new method, fluorochemicals are made directly from CaF2, completely bypassing the production of HF: an achievement that chemists have sought for decades.

This advance builds on decades of research from the laboratory led by Professor Véronique Gouverneur FRS at the University of Oxford. ‘The direct use of CaF2 for fluorination is a holy grail in the field, and a solution to this problem has been sought for decades’ she says. ‘The transition to sustainable methods for the manufacturing of chemicals, with reduced or no detrimental impact on the environment, is today a high-priority goal that can be accelerated with ambitious programs and a total re-think of current manufacturing processes.’

By commercialising this technology, we aim to enable the development of safe, sustainable, and cost-effective synthesis of fluorocarbons worldwide. We hope that this study will encourage scientists around the world to provide disruptive solutions to challenging chemical problems, with the prospect of societal benefit.

Professor Véronique Gouverneur FRS, Department of Chemistry

In the novel method, solid-state CaF2 is activated by a biomineralization‑inspired process, which mimics the way that calcium phosphate minerals form biologically in teeth and bones. Professor Véronique’s team ground CaF2 with powdered potassium phosphate salt in a ball-mill machine for several hours, using a mechanochemical process that has evolved from the traditional way that we grind spices with a pestle and mortar.

The resulting powdered product, called FluoromixTM, allows over 50 different fluorochemicals to be made directly from CaF2, with yields of up to 98%.

Calum Patel, a DPhil student in the Department of Chemistry, and one of the researchers leading this work, says: ‘Mechanochemical activation of CaF2 with a phosphate salt was an exciting invention because this seemingly simple process represents a highly effective solution to a complex problem; however, big questions on how this reaction worked remained. Successful solutions to big challenges come from multidisciplinary approaches and expertise, I think the work really captures the importance of that.’

The process represents a paradigm shift for the manufacturing of fluorochemicals across the globe, and led to the creation of spin‑out company FluoRok in 2022. With the method being suitable for both academic and industrial applications, the research team hope it will ultimately lead to significant impacts in minimising carbon emissions (e.g. by shortening supply chains) and increasing the reliability of fluorochemical supply chains.

As Professor James Naismith, Head of the Mathematical, Physical and Life Sciences Division at Oxford University, says, these examples demonstrate how Oxford is leading the way to develop innovative solutions to our most pressing challenges. 'It is only through innovation that we can both improve the quality of life and stop damaging the planet' he says. 'Chemists at Oxford are leaders in green chemistry; the science behind sustainability. The range of work highlighted here includes materials from biology that could replace the fossil fuel-derived polymers modern life depends on, zero impact materials for lithium batteries, and replacing the use of waste-generating hazardous processes for chemicals which we can’t yet do without. The future is being made in Oxford by our talented researchers and students; this is a global effort with partnerships spanning the world.'

Green chemistry, also called sustainable chemistry, is defined as ‘the design of chemical products and processes that reduce or eliminate the use and generation of hazardous substances’ by the European Environmental Agency (EEA). Interest in this area has been increasing since the 1990s, with the US Environmental Protection Agency and the Royal Society of Chemistry’s journal, Green Chemistry, playing an important role.

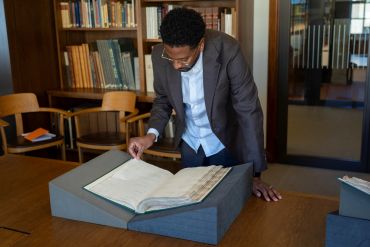

Acclaimed baritone Peter Brathwaite was in conversation at the Bodleian libraries this week, as part of its new racial equality event series We Are Our History Conversations. His talk, on the theme of ‘Black Lives in the Archives’, was inspired by his mission to uncover the forgotten and unheard voices of black and enslaved people from history, including those of his own ancestors.

In conversation with Professor Farah Karim-Cooper, Professor of Shakespeare Studies at King’s College, London, the opera star talked about his journey through the Bodleian’s archives to discover his own enslaved ancestors on Barbados – and hear their voices in between the lines of letters which mentioned them just in passing.

Peter Brathwaite

Peter Brathwaite

He began the project during the pandemic – as he personally reinterpreted dozens of pictures, including one of him as President Obama, as well as him as ancient kings, queens, saints, servants, slaves and even as a Black Madonna. It is both a playful and deeply insightful series. He says, ‘I recreated one every day for 50 days…Black sitters were often unknown or not yet known, as I prefer to say. They needed filling out, a narrative to be constructed and that’s what I was trying to do.’

Peter personally reinterpreted dozens of pictures, including one of him as President Obama, as well as him as ancient kings, queens, saints, servants, slaves and even as a Black Madonna....He says, ‘...Black sitters were often unknown or not yet known, as I prefer to say. They needed filling out...and that’s what I was trying to do

Mr Brathwaite continues, ‘I wanted to hear what they were saying. They had been imagined through the white gaze and I wanted to look at them through the eyes of the sitter.’

It is this approach which has seen the singer engage in months of passionate scholarship in Barbados and in the UK, looking for traces of his ancestors in archives not written from their perspective or even with them in mind.

‘I always had this urge to dig. I wanted to shift the perspective and so I read around the subject extensively,’ he explains. ‘I wanted to learn more about these real people from history.’

His research has proved very successful, although extremely difficult at times, as he uncovered the lives of his enslaved ancestors and learnt more about his forebears.

‘I am descended from white enslaving plantation owners [from whom the name Brathwaite comes] and from enslaved black people…it’s messy, but we think my four times great grandfather, Addo Brathwaite, came from Ghana.’

I am descended from white enslaving plantation owners [from whom the name Brathwaite comes] and from enslaved black people…my four times great grandfather, Addo Brathwaite, came from Ghana

Peter Brathwaite

Clearly passionate to know more, he tells the story of how he found this ancestor named in letters in the Bodleian – revealing a tantalizing glimpse of what may possibly still be uncovered.

Addo had been brought to the West Indies to be a field slave, he became a house slave, and eventually was a free person of colour. Through his research, Peter has found, Addo and his wife Margaret, who was of mixed race, worshipped at the local black church – a fact noted in the Bodleian letters. When he came upon the letters, he was stunned to discover they mentioned his ancestors by name and revealed the couple were seen by the author as respectable examples for the enslaved people of the island.

Peter Brathwaite at the Bodleian

Peter Brathwaite at the Bodleian

But, says Peter, by reading against the grain, he tried to find the real Addo and Margaret and the submerged West African culture from which Addo had been taken.

‘Going to church was not just an expression of their faith, but also of the new society in which they lived. But there are hints of the culture: the fact that in Ghanian tradition, women are keepers of generational knowledge and Margaret established the tradition of having a family festival on 2 July each year – which is still going and is similar to the Yam festivals in West Africa. And they established a family village in Barbados, for their extended family.’

There are hints of the submerged culture: the fact that in Ghanian tradition...they established a family village in Barbados, for their extended family

Peter Brathwaite

Also, he says, for the festival, Margaret asked for the hymn ‘Hark, my soul! It is the Lord,’ which was written by a well-known abolitionist.

Peter discovered Margaret had been freed by her own half-brother, John. Their father was one of the infamous Brathwaite’s, who Peter says, it has been hard to avoid in his research. The young John had attended Christ Church – and Peter wonders if he ever brought Margaret to Oxford with him, as did happen with favourite slaves.

‘It’s pain-staking work,’ Peter says earnestly. ‘But you can find little nuggets. It’s really important for people to hear this. If you move away from the data, you can find the people behind the numbers.’

It’s pain-staking work...But you can find little nuggets. It’s really important for people to hear this. If you move away from the data, you can find the people behind the numbers

Peter Brathwaite

When he stumbled on the names of his own ancestors, Peter had been stunned, ‘To turn the pages and absorb - the effect was incredible. It was an encounter with the archives.’

But, he warns, it was something that needs to be done with care because of the ‘visceral violence’ and challenging terminology of the historic papers. He says, ‘It is not easy.’

Jasdeep Singh, Project Manager for the Bodleian’s We Are Our History initiative, explains how the libraries are working to reveal hidden stories in the archives and make them more publicly accessible, with the project, ‘We’re taking a fresh look at imbalances in the collections. From digitization to exhibitions, we’re looking at the impact of the colonial era in the libraries.’

Royal Opera House, 'Insurrection A Work in Progress' by Peter Brathwaite. Highlighting Barbadian folk traditions as a form of resistance.

Photo Credit: Sama Kai

Most of the colonial papers dominated by the voice of officials, researchers in this area are often left with fragments of history that detail the silenced voice...But sometimes, those fragments are brought together by people like Peter. When these surface, they make really powerful stories

Jasdeep Singh, Bodleian libraries

Peter concludes, ‘Not everyone can find their family history. You feel in the dark and grasp at little clues. So much is lost. There is an overwhelming silence. It is deafening.’

The Bodleian's We Are Our History project was inspired by the famous James Baldwin quote: 'History is not the past. It is the present. We carry our history with us. We are our history....'

For further information about the We Are Our History work, and conversations series visit the project website here: We Are Our History | Bodleian Libraries (ox.ac.uk)

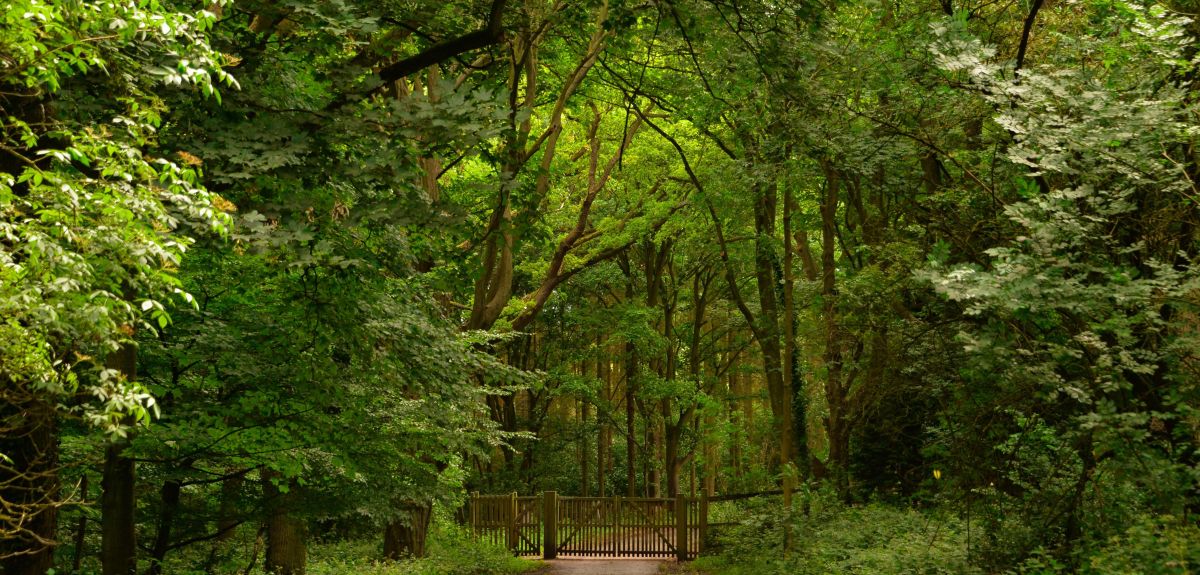

Professor Andy Hector describes a unique living resource, Wytham Woods, and how this contributes to the distinctive and immersive learning experience for students at Oxford.

Four miles northwest of Oxford’s city centre lies 1000 acres of woodland and grassland – an outdoor living lab for Oxford’s students and academics. Owned and maintained by the University since 1942, Wytham Woods is home to over 500 species of plants, a wealth of woodland habitats, and 800 species of butterflies and moths.

Professor Andy Hector at Wytham Woods (c) Monica Gujral

Professor Andy Hector at Wytham Woods (c) Monica GujralNow entering its eight year of data collection, the project, he says, relies heavily on Oxford’s students: “The Masters and the PhD students in particular, are really key to keeping the research going. Of course, it does mean projects need to be fairly unique. We can't just keep repeating the same things over and over, so it does pose the challenge of coming up with new ideas, and they have to be ones that the students are also interested in.”

PhD student Sara Middleton at the field site (c) Steven Pocock/Wellcome Collection

PhD student Sara Middleton at the field site (c) Steven Pocock/Wellcome CollectionEqually, Professor Hector says, Wytham is important for PhD students who in general have relatively limited time and resources: “If you’re at a university that’s lucky enough to have an outdoor laboratory, which is what Wytham is to us, then we can have these long-running studies. The students can come in and hit the ground running and take advantage of all the past investment and long-running studies undertaken there.”

One of those students is Sara Middleton, a doctoral researcher in plant ecology and drought, who has been focusing her research on one specific species of grass within the ecosystem and is currently writing up her PhD thesis.

Undergraduate biology students on their orientation day (c) Monica Gujral

Undergraduate biology students on their orientation day (c) Monica GujralFrom 2020, the Department of Biology has offered an optional research-focused fourth year as part of an integrated masters and many choose to complete their field-based work at Wytham Woods.

So, what do students think when they visit Wytham? “Students react in different ways to Wytham”, says Professor Hector. “The undergraduate biology degree at Oxford is incredibly broad so you will have students with an interest in genes and cells to those who are more interested in organisms, whole ecosystems and conservation. Some people haven’t spent a lot of time outdoors, which can be challenging if the weather is not good. For others you can tell that they are delighted they can take advantage of this outdoor lab right on our doorstep, and interestingly by having a go some people might reconsider what appeals to them.”

What’s the best time of year there? “So as an outdoorsy person, I actually like Wytham at all times of the year! Even in February, with the leaves off the trees you can really see further through the vegetation. If I had to pick - June or July - before the hay is cut and it’s really looking at its best with most of the flowers in bloom”.

Find out more about Wytham Woods here.

- Randomised control trials in Kenya, show cash payments most effective at delivering aid where it is needed

- Based on the research, during pandemic, the South African government used cash payments to reach 28 million people - far more than possible with food parcels

- Researcher Dr Kate Orkin, who led the trials, which saw 5.5 million kept out of food poverty, has been nominated for an ESRC Impact Award.

Nearly 10 million South Africans were going to bed hungry in the early chaotic days of the COVID-19 pandemic. With a hard lockdown in place and some three million people thrown out of work, it was proving impossible for the government to deliver adequate food parcels to the overwhelming majority of those in need. The logistics involved were simply unfeasible.

But based on some new university research, led by Oxford’s Dr Kate Orkin, the South African government did the unthinkable: they gave cash to those in need, and not just a little amount, but large sums of money to support families over the months of the crisis.

There is a stereotype of how people in poverty behave. But, studies have found, this is simply not accurate. People think really hard about the best way to spend the money

Dr Kate Orkin

Not only did the resources reach those in need, it enabled them to buy food, plan for the future and for children’s education.

It was an enormous success and Dr Orkin and her team have been nominated for a prestigious ESRC impact award – for social science research which makes a difference in the world. And it did make an enormous difference.

Together, the team’s recommendations in terms of cash payments influenced spending of ZAR 97.5bn (£4.87bn) which reached 28.5 million people in South Africa, helping to avert a national disaster. Research has shown recipients were both able to provide for today and plan for tomorrow – buying food, setting up businesses, finding new work.

It had been widely believed food parcels were the best way to alleviate urgent need – especially in the developing world. The argument went that, if you gave cash to people in need, they would simply squander it.

But Dr Orkin’s research, based on formal randomised control trials in Kenya, showed that, far from squandering cash, poorer people used it carefully and wisely to improve their lives. And it had wider benefits, even helping those who did not receive the cash, because the money was spent locally.

Dr Orkin says, ‘If you give people the money, it gives them autonomy and they use it for the things they need, including food and healthcare.

The South African government was able to reach more people more quickly...Food parcels can end up being the wrong food and they are so difficult to provide in huge numbers and they can undermine local vendors

Dr Kate Orkin

‘There is a stereotype of how people in poverty behave. But, studies have found, this is simply not accurate. People think really hard about the best way to spend the money.’

She explains, ‘Many people made long term investments – putting a steel roof on their house – or starting a business. The trials we had run in Kenya had shown this to be the way to deliver aid, rather than food parcels.’

‘The South African government was able to reach more people more quickly,’ she says. ‘Food parcels can end up being the wrong food and they are so difficult to provide in huge numbers and they can undermine local vendors.’

According to Dr Orkin, similar trials had been conducted elsewhere internationally and similar programmes were run in various locations, including Colombia and now aid agencies, including UNICEF and ICRC are adopting the same approach.

‘It wasn’t all us,’ she laughs. ‘There is strong evidence from other trials as well.’

‘It was a big shift for the South African government, though,’ says Dr Orkin. ‘They switched to cash emergency aid and reached more people immediately. Previously, they had delivered one million food parcels in a week. The cash reached more than 28 million in five weeks and kept 5.5 million people out of food poverty.’

It was a big shift for the South African government...Previously, they had delivered one million food parcels in a week. The cash reached more than 28 million in five weeks and kept 5.5 million people out of food poverty

Academic research has previously been recognised to provide answers and solutions to many great scientific questions and problems. But the ESRC award is to recognise that social science researchers can also provide real-life impact. In this case, it put paid to a widely-held and long-lasting belief. Randomised control trial evidence transformed lives in the most difficult circumstances.

This summer, 127 students from across the UK came to Oxford to participate in UNIQ+ - the university's flagship graduate access programme that provides students from underrepresented or disadvantaged backgrounds with the opportunity to experience life as a graduate research student. The 7-week programme sees students undertake a research project and attend training skills and information sessions, as well as meeting and working with Oxford researchers, academic staff, and graduate students.

Here we hear from UNIQ+ supervisor David Gavaghan, Professor of Computational Biology at Oxford, and his 2023 UNIQ+ interns, Talal and Kamil, to find out more about their experience of the programme.

Professor Gavaghan, can you tell us about your role at Oxford?

This is my 37th year at Oxford - I came in 1986. I came here for one year to do a master's degree and never quite escaped, although it’s quite a nice place to get stuck!

I particularly work with industry, so looking at how we can use computational biology to establish whether new drugs are likely to cause toxic side effects on the heart and the way that disease spreads, for instance during the Covid-19 pandemic. An academic project I have looks at whether we can engineer bacteria to produce hydrogen and oxygen from waste products which would help tackle climate change. A huge range of things, and what ties it all together is that the mathematics is pretty much identical for all of those things, surprisingly!

My main job these days is running the Doctoral Training Centre, which has four different programmes for DPhil students. We take around 100 students a year and we try and get them to work on problems in the life and natural sciences, with students coming from the complete range of science backgrounds.

How are you involved in UNIQ+?

I’m Chair of the Graduate Access Working Group at Oxford, which has been going for about four years now. One of its first initiatives was UNIQ+, to support underrepresented groups and socio-economically disadvantaged undergraduate students from the UK. This is our fourth iteration of the internship programme. We started with thirty-three students in 2019 and then Covid happened, so the second year was a scaled back digital programme and we had about 115 students. In 2021, we ran a mostly online internship programme, then in 2022 and 2023 we’ve been able to open the programme to 130 students.

You’ve also been supervising two UNIQ+ interns this summer. What have you been working on?  Professor Gavaghan and UNIQ+ 2023 intern Kamil

Professor Gavaghan and UNIQ+ 2023 intern Kamil

What do you enjoy most about being a supervisor?

Getting to interact with the students. They’re so enthusiastic, they’re enjoying being in Oxford, they’re working hard and clearly getting a lot out of it. The point about UNIQ+ is that students who are under-represented in graduate study at Oxford come here and discover that it’s just like any other university. It’s just a really good university and a great place to study. That’s the thing I like best about it. One of the goals is that everyone who has the potential to succeed here considers it as somewhere they might go.

Do participants tend to go on to graduate study?

It varies from year to year. It is certainly making them think hard about whether they want to do graduate study, and that’s one of the interesting things - if they’ve already got a job - whether they’ll come back later and do graduate study having done this. It might put it in their heads.

Before arriving in Oxford for UNIQ+ Kamil had been at UCL studying Computer Science, and Talal had been studying Discrete Mathematics (Maths and Computer Science) for his undergraduate degree at Warwick University.

UNIQ+ 2023 intern Talal

UNIQ+ 2023 intern Talal

Talal: No, this is actually the first time. I think I visited Oxford when I was quite young on a year 9 or 10 trip, but this is the first time I've come to Oxford by myself and explored the city.

Kamil: I was born and raised in Northampton, so not far from here. I did the undergraduate UNIQ programme at Oxford before going to university and that's one of the reasons I applied for this because it seemed like that natural progression.

Could you tell us a bit about the research you've been doing over the last seven weeks?

Talal: The first week was training. The thing I really enjoyed was that it was structured in a way that if you wanted to do the more advanced topics, if you were comfortable with the easier topics, you could go ahead and do that. Then after that we pretty much got straight into the research.

Usually you have information and from that you produce data, but in our project we were given the data and we're essentially going backwards to produce the information. So for the bubonic plague that would be trying to find out what the contraction rate was for the plague, the average life expectancy, the mortality rate.

Kamil: The project was to understand the problems faced by people doing statistical inference for the first time, so we were kind of thrown in at the deep end and left to work it out for ourselves. So there was a lot of trial and error, and just trying things out. We got better at recognising what does work and going in the right direction. Now I see why a lot of the things we tried didn’t work!

Why computational biology? What was it about this study area that you were interested in?

Talal: I really wanted to get into something that had a machine learning aspect to it because I have a general interest in that. All the projects that I've done have really just been focused on pure computer science and mathematics and I thought that maybe delving into the biology aspect and looking at computer science in a different way would give me the skills to expand my palette. And I thought it'd be really interesting to see how computational biology actually works.

Kamil: It was similar for me as well. I’d not had any experience with computational biology and I didn't really even know what it meant when I applied for it. But at UCL I found that I liked to apply the maths that I learnt rather than just learn the maths, and so the project itself gave me a good opportunity to do that.

What’s been your highlight over the past seven weeks?

Kamil: I have liked the formal dinners. I think it's a normal College experience for a student here, but it's something different because at most universities in the UK they don't have this kind of thing. It's a lot more chilled than doing the project all the time - there are plenty of events for you to meet other interns and loads of opportunities to socialise.

Talal: Yes, I’d definitely say the same. The dinners, they really were spectacular. Going into the colleges and seeing the inner halls and the traditions of every college is quite remarkable. And you also get to meet everyone else from the programme as well as DPhil students and professors.

Has anything particularly surprised to you about UNIQ+ or about Oxford itself?

Kamil: There's a lot of support by the supervisors. They all clearly know their field very well. Some of the concepts are hard to grasp, which I expected, but it's definitely doable.

UNIQ+ supervisor David Gavaghan and interns Kamil and Talal

UNIQ+ supervisor David Gavaghan and interns Kamil and TalalTalal: I think I was just surprised about how big Oxford University actually is and it's really nice how it's incorporated within the city. You have access to so many libraries. However you’re feeling you can always find a different place to study, which I really like because I was used to just having one library to go and study.

What would you say to somebody who's thinking about applying for the programme and wondering if it's for them?

Kamil: If you've got a genuine interest in any of the projects you should apply. Even if you don't have much knowledge going into that project, still apply. Talal and I didn’t have knowledge of computational biology and we've done just fine. I’d also say that the application process was quite easy and concise.

Talal: The worst thing that can happen is that they'll say no, but if you ever feel like you shouldn't apply because you feel like your application’s not going to be strong enough, I would highly disagree with that. It’s open for everyone that has interest in research.

What your plans are for the future?

Talal: I'm doing a masters apprenticeship after this. I knew I wanted to do a masters but coming here and speaking to the DPhil students, I definitely want to think about doing a DPhil in the near future, after I've done my masters and maybe worked for a bit and saved up a bit of money.

Kamil: After graduating, I'm going to go to Microsoft as a software engineer. But I still want to keep the doors open for postgraduate study. UNIQ+ has convinced me that maybe I should take that route. I definitely wanted to apply for a masters, but the internship’s swayed my way more to a DPhil as well. But that's all in the future, I haven’t thought too much about it yet.

Find out more about UNIQ+ here.

- ‹ previous

- 3 of 247

- next ›

From research to action: How the Young Lives project is helping to protect girls from child marriage

From research to action: How the Young Lives project is helping to protect girls from child marriage  Can we truly align AI with human values? - Q&A with Brian Christian

Can we truly align AI with human values? - Q&A with Brian Christian  Entering the quantum era

Entering the quantum era Can AI be a force for inclusion?

Can AI be a force for inclusion? AI, automation in the home and its impact on women

AI, automation in the home and its impact on women Inside an Oxford tutorial at the Museum of Natural History

Inside an Oxford tutorial at the Museum of Natural History  Oxford spinout Brainomix is revolutionising stroke care through AI

Oxford spinout Brainomix is revolutionising stroke care through AI Oxford’s first Astrophoria Foundation Year students share their experiences

Oxford’s first Astrophoria Foundation Year students share their experiences DPhil student, Frankco Harris, reflects on his unique journey to Oxford and future plans

DPhil student, Frankco Harris, reflects on his unique journey to Oxford and future plans Oxford undergraduates reflect on their first term

Oxford undergraduates reflect on their first term