Oxford, heritage & conflict

Why Oxford archaeologists dream of seeing the Palmyra Arch rebuilt by Syrians.

As Islamist militants are driven finally out of their captured strongholds, Oxford archaeologists have urged that the restoration of damaged historic sites be made a priority.

Monuments and buildings such as the Palmyra Arch or the Great Mosque in Aleppo should be rebuilt with Syrian expertise and materials not only because of what they say about the ancient world, but also because of what they can do for the economic and spiritual well-being of local people.

When so-called Islamic State (IS) seized Palmyra in 2015, its militants beheaded the Syrian city’s 82-year-old archaeologist Khaled el-Asaad and destroyed the Temple of Bel that had stood there for 2,000 years, followed by the 1,800-year-old Roman Arch of Septimius Severus nearby. As international public outcry seemed to condemn the iconoclastic destruction more than the murder, ‘compassion fatigue’ was blamed. It is a debate that resurges every time historic heritage is blasted by war. But Oxford archaeologists and historians argue that it is misguided to weigh lives and buildings against each other like this.

‘The built environment is part of people’s identity,’ said Oxford classical archaeologist Dr Judith McKenzie. ‘Historic buildings are part of people’s culture, history, and memories. And handing down cultural heritage from past to future generations reaffirms identity.’ This is not a matter simply of bricks and mortar, but what she called ‘intangible heritage’ – the value that people and buildings have mutually generated across time.

Lighthouse in a storm

One timely innovation by Oxford University is offering a second life for historic monuments and other heritage sites destroyed in current conflicts in the Middle East and beyond.

Manar al-Athar, a databank of photographs taken by archaeologists and art historians, was conceived by McKenzie just before the region plunged into destruction. It now carries some 30,000 photographs, with a large and ever-growing archive still being uploaded.

Crucially it aims to help archaeologists from the stricken countries study their own national heritage – and to help them boost appreciation there not only of lost treasures, but of the ones that survive. The name, literally ‘Guide to Archaeology’ in Arabic, implies much more. In Egypt manar denotes Alexandria’s lighthouse, the wonder of the ancient world that gave the Islamic minaret its form and name. Through photography (literally ‘drawing with light’ in Greek), the site illuminates the past and provides a beacon for the future.

The idea came to McKenzie in 2009–10 when she was working in the Middle East with local archaeologists unable to visit historic sites of their heritage because of politics or war. By the time the pilot Manar al-Athar website had been launched in 2013, Muammar Gaddafi had fallen, Libya was on the brink of further violence, and Syria was eye-deep in hell.

‘We didn’t know there was going to be this tragedy of war,’ McKenzie said. ‘The website has had an unintentional usefulness in recording a lot of material that it’s no longer possible to get at, and things that have since been destroyed. We have important records for the future.’

The site is in both English and Arabic, with no paywalls or copyright restrictions. The images can be downloaded free, without form-filling, in multiple sizes fit for teaching and publication alike. An honour system stipulates only that credit be given. Unlike the unreliable amateur or automated information available on online image resources such as Instagram and Google Images, Manar al-Athar’s photographs are labelled meticulously by researchers with access to the unparallelled art history and ancient history collections at Oxford’s Sackler Library. The images are edited and carefully sequenced to show visually the context of details. Research is critical to identifying important features to record, and their significance.

The website was populated first with images from McKenzie and Neil McLynn’s Leverhulme Trust funded project on the transformation of sacred spaces in Egypt and the Holy Land from pagan to Christian to Islamic. With additional funding from a John Fell OUP Research Grant, the British Academy and elsewhere, further image sets have come from former Australian ambassador to Syria Dr Ross Burns, Harvard Semitic Museum’s Dr Joseph Greene, Canberra art historian Professor Michael Greenhalgh and Oxford colleagues such as Professor Andrew Wilson. More are coming from Oxford-based expeditions to Byzantine antiquities in the Caucasus and the Balkans, and from McKenzie’s European Research Council project on the monumental art of the Christian and Early Islamic East. Oxford’s resources are ‘critical to being able to do what we do’, said McKenzie.

The project could snowball. But labelling and uploading take time, and grant bodies favour active research rather than platforms like Manar-al-Athar which aim to support the research of the future. ‘With more resources we could do a lot more, a lot more quickly,’ said McKenzie, who has spent five years trying to balance research with ‘dead exhausting’ fund-finding.

McKenzie’s hope is that Manar-al-Athar’s Arabic–English bilingualism will set a new international standard. Ross Burns thinks peer institutions in Europe should emulate the Oxford ethos of outreach embodied in the website. ‘The tradition in a lot of the German and French universities is to keep all this information so no one gets it and publishes it first, but I don’t get that sense here,’ he said while visiting Oxford for a conference this year – HERITAGE: Rebuilding the Future from the Past – hosted by Oxford University’s Classics Faculty. ‘There’s much more of a mission to spread knowledge to a wider community – and by putting it into Arabic, to a community that includes the Arab world at large.’ The bilingual standard has been adopted by Burns for his own Monuments of Syria website, and by the website of an important Oxford-based aerial archaeology venture, EAMENA.

Archaeology from above

The vast scope of EAMENA – Endangered Archaeology in the Middle East and North Africa – belies its origins in a smaller venture to document the ancient heritage of Jordan from above. Dr Robert Bewley, now project director at EAMENA, still co-directs and photographs for the Aerial Archaeology in Jordan project. ‘There was more than just discovery here,’ he said. ‘We were recording and monitoring the process of destruction.’

EAMENA took off in 2015 thanks to a proposal from the Arcadia Fund to record endangered archaeology in the Middle East and North Africa. It is a massive exercise in aerial archaeology, a discipline still eyed with suspicion by some old-school archaeologists but which, in Bewley’s view, is the only way to document heritage across such a wide area before it is damaged irreparably. Based at Oxford’s School of Archaeology, partnered with Durham and Leicester, the £3.275 million project will run for at least three more years.

‘It’s hugely ambitious, but it’s exactly the right thing to do,’ said Bewley. A key goal is making EAMENA’s information accessible for free ‘to as many people as possible who can actually then do something with it’ – principally, the archaeologists of the 21 countries covered, from Mauritania to Iran.

Each site discovered through satellite imagery is marked on a digital aerial map, with information on the date and nature of the archaeology, and the kind of threat it faces. To counter the risk of looting, information for enquirers without archaeological credentials is strictly limited. Online access was launched in April 2017. Of the 150,000 sites already on the database, 20,000 are judged to be under threat.

Aerial images eloquently demonstrate the damage done by militants and by war. In 2011 Dura-Europos, an important Roman–Hellenistic site in Syria, looked virtually unchanged from the third century AD (apart from the excavations and spoil heaps of archaeologists). A 2015 photo shows a dense rash of pits dug by looters licensed by IS to raise money for its brutal campaigns. ‘The looting is on an industrial scale,’ Bewley told the HERITAGE conference.

Endangered archaeology

The Middle East and North Africa has an incredible number of archaeological sites, reflecting its vibrant and complex history. But this region's archaeology faces huge risks from looting, population growth, agriculture and many other pressures.

Political chaos, too, can be a stimulus for destruction. A 2010 satellite photo from eastern Egypt shows small huts dating back to ancient mineworks. In another from three years later the landscape is barely recognisable. ‘Because of the financial crash in 2008 and a breakdown in law and order after the Arab Spring, mining companies bulldozed that area, at it became cost-effective to make money by selling precious metals as their value had increased.’

Yet Bewley warns that the chief threats to global archaeological heritage are urban development, infrastructure, dams, irrigation and (biggest of all) agriculture. EAMENA’s urgent priority is to tackle areas where major building works or infrastructure are planned.

On the upside, EAMENA is also revealing previously unremarked archaeological sites that are amazingly well preserved, with extraordinary features that beg to be understood. Bewley hopes the project will galvanise action internationally, nationally and locally to protect such sites. He urged the HERITAGE conference: ‘Let’s preserve them, and keep them preserved so the random railroad or bypass or town isn’t put there – or if it is, we can do an archaeological investigation in advance.’

Oxford’s name and connections count for much. ‘In the Middle East and Africa, if you say you’re from Oxford University they’ll at least have heard of it – and it has a good reputation.’ The idea is to use Oxford’s resources to help local experts in countries where archaeology is tragically underfunded and understaffed. ‘We want to build something for them which they couldn’t do on their own because of the conflicts in their countries or because there’s no infrastructure or no money.’

One key aim is to help national governments create their own archaeological inventories, as it is now doing with Yemen. EAMENA also aims to train 120 archaeologists throughout the Middle East and North Africa by 2020, with a £1.6million grant from the UK Cultural Protection Fund. ‘That is the endgame – this is their information, archaeology, history,’ Bewley said. ‘The local community is absolutely crucial. Unless there are people on the ground who value what they’ve got, our work won’t have the benefit we’d like it to have.’

Whose heritage, whose reconstruction?

Judith McKenzie’s convictions about the ‘intangible heritage’ vested in historic sites by those who live among them are shared by other Oxford academics.

Images of devastation in Syria shown by McKenzie ranged beyond Palmyra to parts of the city of Hama now utterly erased for political reasons, and to the mosques, souqs and churches that once knitted Aleppo’s communities together. Even the iconoclasm of IS – extending in Mosul, Iraq, to the destruction of items from ancient Sumeria – confirms the importance of heritage sites to those who live among them. By destroying monuments and relics, the militants aim not only to grab headlines and remove supposedly un-Islamic relics, but also to crush morale and erase local identity.

IS is not the only guilty party. Nor is the ideology of radical Islam the sole motivation for destruction of heritage. The devastation of old Aleppo predated the rise of IS and was carried out by all sides, according to Burns, whose time as Australian ambassador to Syria led him to write The Monuments of Syria and Aleppo: A History. ‘Virtually all parties to the fighting have sought to use the country’s monuments as either weapons or propaganda tools,’ he said.

The West is home to several prime examples of sites restored to their old aspect after being destroyed in war. The centre of Dresden is one, with baroque churches and galleries rising again where Allied firebombs left only smouldering ruins in 1944. The heart of Ypres is another, with the cathedral and market square once more standing as proud as they did before the First World War reduced the Belgian town to a ghost.

The Palmyra Arch is probably the most famous present-day icon of heritage destroyed in the Middle-Eastern war zones. Oxford University physicist Dr Alexy Karenowska led a team that last year created a one-third scale replica. She runs a University research group which is developing technology – especially photography and 3D-printing – for documenting and preserving cultural heritage and archaeological material. Her work on the replica was part of her spare-time role as director of technology at the independent Institute for Digital Archaeology (IDA), but it earned her an Early Career Researcher award in this year’s Vice-Chancellor’s Public Engagement with Research Awards, which celebrate public engagement work across Oxford University.

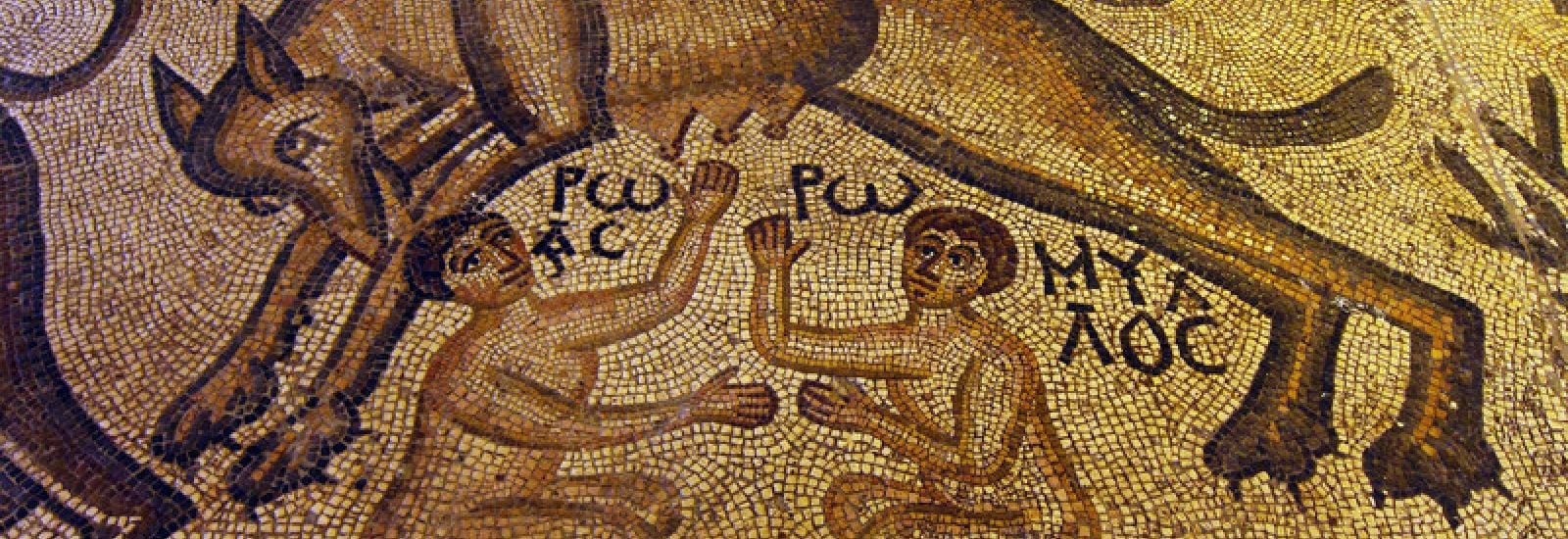

The replica was conceived by people in Syria – the IDA working closely with the Director-General of Antiquities and Museums there, Professor Maamoun Abdulkarim – and supported by UNESCO and the United Arab Emirates government. Karenowska’s team developed a three-dimensional computer model of the Arch by photogrammetry, which establishes precise surface measurements using photographs. This became the template for the state-of-the-art 3D machining process that produced the 13-tonne replica, in Egyptian marble, of the central opening of one side of the Arch. Karenowska has managed the installation of the replica in London, New York, Dubai and Florence in a tour to raise awareness of the loss to global heritage – it has now been seen by more than two-and-a-quarter million people.

She sees the Arch replica as a demonstration of how science can serve ‘art, beauty, human understanding, and humanity’, not just progress and technology. ‘It’s come to express connections between people in sympathy,’ she said. ‘It’s a gesture of hope, it’s a demonstration of how peace and positivity through human intervention can succeed over violent destruction.’ The educational value is inestimable, she argues – especially for children, whom it has reached in a way that textbooks cannot.

‘This is not black-and-white columns of data,’ said Karenowska. ‘It’s information that has an existence that transcends its physical reality and belongs to the people – whether it be the human race in general or individuals who might feel a particular attachment to a particular historical object.’

The replica is not without its detractors. In response to the declaration that the replica would ultimately ‘go home’ to Palmyra, the London Evening Standard opined: ‘Even if well intentioned, erecting Italian-cut Egyptian stone in the middle of Syria is about as far from authentic as you can get.’ The Factum Foundation for Digital Technology in Conservation has taken issue with its accuracy.

McKenzie points out that the whole arch was the most complex in the entire Roman empire, with its triangular footprint to smooth the angled intersection between two streets, and with exquisite friezes carved by Palmyene sculptors. She and Burns believe the Arch should be rebuilt on its original site, at full scale, using local materials. It could not, of course, be the original piece of antiquity, which is irrevocably gone, and such projects rightly provoke debates about authenticity in the preservation of antiquities. But it would bear witness to nearly 1,800 years of the original’s existence, would allow visitors to Palmyra to see what has been seen before, and might stand for many lifetimes. And as the best way to bring income to the local population and to restore the Arch’s role in Syria’s national identity, McKenzie and Burns argue, that job of rebuilding should be done by Syrian artisans.

Panellists at the Oxford HERITAGE conference were united in condemning the view that only the West has the expertise and sagacity to look after sites and objects of global historic significance. ‘That thinking is so old hat,’ Burns said in his presentation. ‘These are buildings that Syrians themselves visited by the tens of thousands on the weekends before the war. They know what they’re worth. It’s very important that we keep that at the top of our agenda when we look at the question of reconstruction.’

There are anxieties that if reconstruction is done by citizens of war-wracked nations it will favour one particular faith and facet of history at the expense of others. But Edmund Herzig reports that in Afghanistan, the predominantly Muslim restorers have paid particular attention to Buddhist relics, recognising that these are the part of the national narrative that distinguishes the country from its neighbours. He added: ‘They are much more anti-Taliban than we are [in Britain]. Their ambivalence towards an Islamising agenda is probably stronger than mine.’ Photographs from the museum at Ma‘arat an-Nu‘man, north-west Syria, testify to a similar spirit, with workers and volunteers stacking sandbags to protect the fifth-century Christian mosaics.

Commercial reconstruction and expansion may seem more pressing – yet in Britain, as EAMENA’s Robert Bewley pointed out, the heritage sector is now the third largest employer, ‘so we ignore heritage at our peril, purely from an economic point of view.’ Bewley cited anecdotal reports that when outside aid agencies asked Iraqis unhomed by an earthquake what the most important thing to do was, they said, ‘Rebuild our citadel.’

Article written by John Garth (www.johngarth.co.uk)

Unlocking the world's oldest mystery script

Computer imaging could be the key, says Oxford linguist.

What is innovation?

"Innovation for us is presenting old and forgotten materials in new and relevant ways. It’s been taking obsolete materials which were a problem, and using modern technology to turn them into a research resource." Dr Sally Crawford, Historic Environment Image Resource (HEIR)