Features

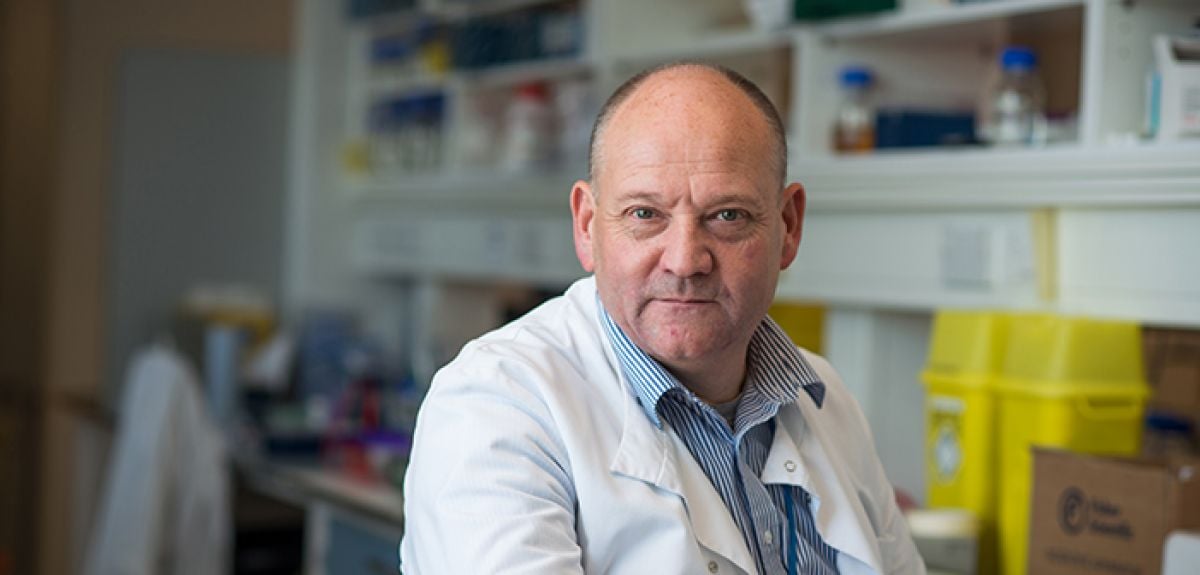

Professor Paul Riley, Director of the Institute of Developmental and Regenerative Medicine discusses how better-designed research buildings can help scientists break out of their silos.

The advances made in medical and biological sciences within our lifetime are staggering. It seems strange to think that the project to sequence the human genome took over a decade to complete back in 2001, yet similar sequencing technology is now portable and is used daily in the field.

Each advance in research has opened up new avenues of exploration and with each new stride whole new research disciplines have emerged. Sadly, in modern science it is impossible to be an expert in more than a few things, despite the fact that most scientists will have chosen their careers early on because of a fascination with all things to do with science, and a desire to keep learning and making new discoveries themselves.

Yet we are increasingly finding, in areas such as our response to pandemics or cancer treatments, it is vitally important that these related avenues of research should remain in contact with one another. The discovery of a new technique in one area could be just as useful to another, and research into complex medical issues is increasingly becoming multi-disciplinary.

Some years ago we began to plan a way of creating a new type of working environment for researchers, which could encourage scientists to mingle more with people from outside their own niche discipline. The logic is simple – scientists are passionate about their work and love talking about it. But the problem with many labs is that most researchers find themselves surrounded only by others from their own field and much of what is going on elsewhere is behind closed doors.

This was the idea behind the Institute of Developmental and Regenerative Medicine (IDRM) – to bring the related disciplines of cardiovascular science, immunology and neuroscience together under one roof, and to design it in a way that increases the chances of these groups mixing socially and professionally, promoting conversations to stimulate new ideas and collaborations between students, post-docs and PIs.

The newly-opened IMS-Tetsuya Nakamura Building is the home for the IDRM, and has been designed around shared common and break-out spaces which differ across each floor in flavour thus linking the laboratories and offices within each discipline vertically to promote mixing and collaboration from the ground-up.

My own research in cardiovascular science involves regular collaboration with colleagues in neuroscience and immunology, who I will now have on my doorstep, and who I can see coming and going each day. Georg Holländer’s group work on how immune cells learn ‘self’ from ‘non-self’ during development. Following a heart attack release of certain proteins from damaged heart muscle triggers a ‘non-self’ reaction, worsening the outcome and promoting heart failure. We can now work together to ask broad questions as to how cells identify ‘self’ and how can we intervene to ensure the body’s own immune response does not react badly during a heart attack. Each experiment and subsequent discovery can be discussed with the immunologists on the floor above in our breakout space.

The siting of the IDRM was also designed to put the researchers at the heart of the science and technology cluster in the Old Road Campus, and between the Headington hospitals where many researchers also work. For example, combining state-of-the-art imaging facilities across the road in the Kennedy Institute with newly purchased microscopes in the IDRM into a new Centre of Excellence will be a powerful tool for many researchers across both institutes and the wider campus.

But the drive to improve cross-disciplinary collaboration goes far beyond just the new building. We are working to improve our links to disciplines within maths to model disease, and the social sciences, such as law and ethics, which will have a major role in shaping and guiding research, as well as collaborations with industry on site, such as Novo Nordisk, and the BioEscalator facility to help turn new research into successful spinout companies that can develop real-world applications.

How effectively we manage to our cross-disciplinary collaborations will play a large part in the speed and efficiency of future research and development and the delivery our findings into clinical care but it will also make a career in science even more engaging.

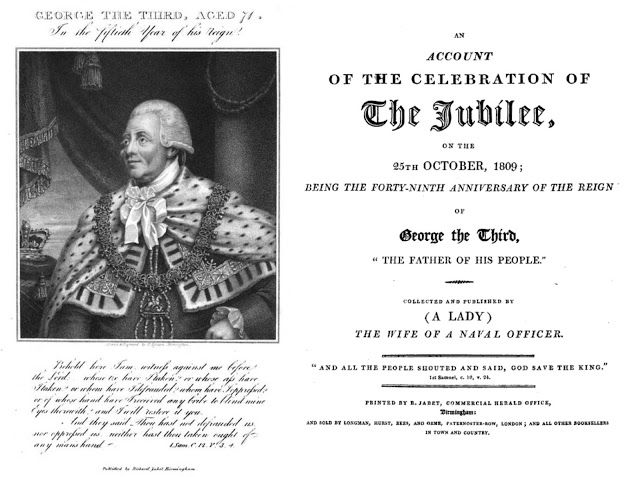

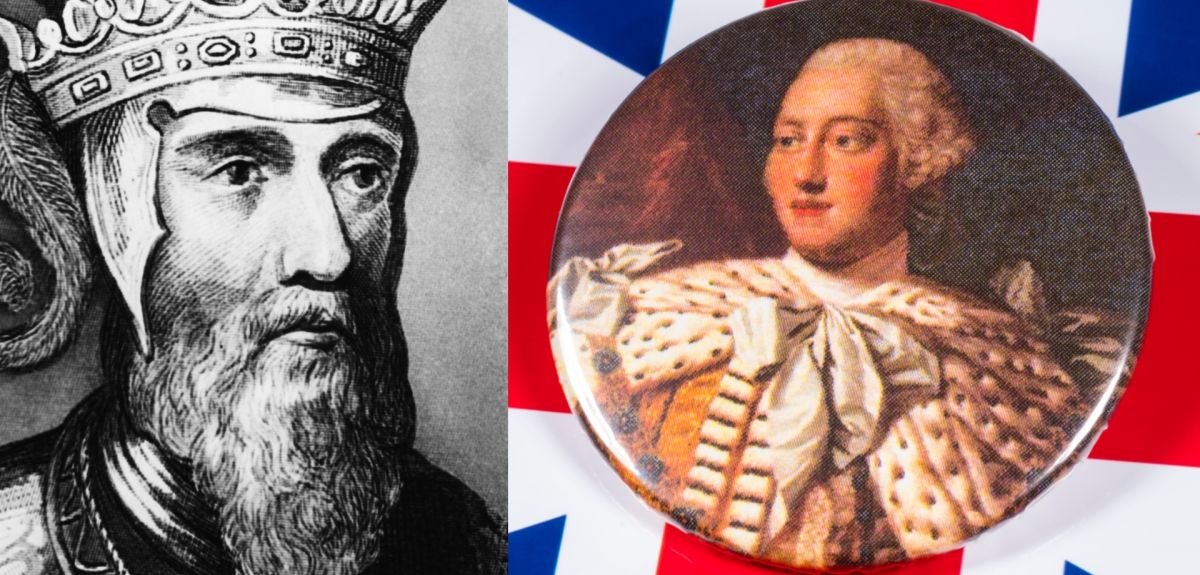

Her Majesty the Queen is the first British monarch to celebrate a Platinum Jubilee, but Royal Jubilees have been celebrated for hundreds of years – complete with military parades, porcelain memorabilia, special coins and much popular enthusiasm. The excitement and pageantry around Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee is well known and preserved in early film and photographs. But a Golden Jubilee was first celebrated by a British king, Edward III, in the 12th century, and Victoria’s grandfather, George III, was acclaimed some 200 years’ ago, for his 50 year reign – in spite of early unpopularity, growing radicalism and debilitating mental illness.

George III. Reign 1760-1820

George III is best known for this long illness and for ‘losing’ the American colonies. But the pattern and many of the traditions around the monarchy and in terms of royal jubilees began in his reign and the monarch came to be seen popularly as synonymous with Britain.

George III: Royal Jubilee

George III: Royal Jubilee Despite this, however, the Hanoverian king eventually came to be associated with patriotism and the essence of Britishness. This, perhaps, began with his person. Most scholars now would say he made poor choices initially, but not many doubt his sincerity and they recognise he took his duties very seriously. He was not a spendthrift and he was a devoted family man and the image started to change.

Edward III. Reign 1327-1377

On 28 January 1377, Adam Houghton, bishop of St David's, addressed the English parliament in the Painted Chamber at Westminster. He told the assembled lords and commons that Edward III had now occupied the English throne for over 50 years, and thus announced the end of Edward’s ‘jubilee year or year of grace’.

The English government had been determined to celebrate Edward’s jubilee year with a series of public spectacles. First, the king presided over a week-long tournament held at Smithfield in February 1376. Second, he played his part in a meeting of the Order of the Garter at Windsor Castle in April 1376. But thereafter the festivities fizzled out. A further tournament that had been planned to take place at Smithfield in June was cancelled. The remainder of Edward’s jubilee year was dominated by the political fallout from the explosive ‘Good Parliament’, which lasted from April to July; the sorrow which met the death of the king’s first-born son – the Black Prince – on 8 June; and the king’s own failing health.

Nonetheless, there were some muted celebrations to mark the day of Edward’s jubilee itself, which fell on 25 January 1377. According to the Anonimalle Chronicle, ‘the commons of London made great entertainment and celebration’, culminating in a show before the Prince of Wales and other members of the nobility in Kennington. However, there are no signs that either the royal court or other towns and cities did much to mark the occasion. Indeed, one man was conspicuously absent from both the celebrations in London and the parliament which opened two days later: the king himself. Edward III was confined to his quarters at his manor of Havering in Essex, and was too unwell to travel; as Houghton explained, he had been laid low and ‘in great peril of his life’. When he finally left Havering the following month, to move to his manor of Sheen in Surrey, a chronicler reported that he made the journey with ‘great frailty’. While the cause of Edward’s ill-health is unclear – although it is likely that he suffered from a series of debilitating strokes – he did not recover, and died on 21 June 1377, at the age of sixty-four.

Although Edward’s infirmity cast a shadow over the last years of his reign, it should not blind us to what he achieved during his fifty years on the throne. When Edward was crowned in 1327, the English monarchy had been in the midst of an unprecedented crisis. His father, Edward II, aroused discontent, distrust, and anger because of his regime’s harsh and heavy-handed treatment of political society; his government’s military failures against both France and Scotland; and his own scandalous relationship with his favourites, Piers Gaveston and Hugh Despenser the Younger. This led to Edward II being overthrown in the first deposition of an English king since the Norman Conquest. Yet over the course of his reign, Edward III rebuilt the monarchy’s prestige and reputation, restored the crown’s relationship with the aristocracy, and revived England’s military fortunes, with English forces triumphing over their French foes at the Battles of Crecy and Poitiers in 1346 and 1356 respectively.

The response to Edward’s death suggests that his subjects appreciated his accomplishments and longevity. The chronicler, Jean Froissart, remarked that his death was ‘to the deep distress of the whole realm of England, for he had been a good king for them’, and described how his funerary procession was observed by mourning crowds. Other commentators also heaped praise on the departed king; Thomas Walsingham, a monk of St Albans, later wrote that ‘among all the world’s kings and princes, he [Edward] had been a glorious king, benevolent, merciful, and magnificent’. But perhaps the most remarkable tribute to the king is the inscription that runs around the perimeter of his tomb:

‘Here is the glory of the English, the paragon of past kings,

The model of future kings, a merciful king, the peace of the peoples,

Edward the Third, fulfilling the jubilee of his reign.

The unconquered leopard, he was a powerful Maccabeus in his wars.

While he lived prosperously, he restored to life his kingdom in probity.

He ruled mightily in arms; now in heaven may he be heavenly king’.

By Sam Lane

The mental illness which affected him was partly responsible for George III’s rehabilitation. He was seen sympathetically as a ‘King Lear-like figure’. And, in a defining 1984 article about George III , Princeton Professor Linda Colley says, ‘After 1789, prints portrayed him regularly as St. George, as John Bull and, after his mental collapse in 1810, as a wise, Lear-like patriarch and the celestial guardian of his nation.’

As well as increasing personal sympathy for ‘Farmer George’, the monarchy became the symbol of Britishness to counter the forces of autocracy that were seen on the Continent.

A mark of the considerable change in mood during his reign, was the reaction to his death in 1820. Some 30,000 people gathered for the funeral, although he had been unwell for the last decade, it was described as ‘if the paternal roof had fallen in, and left our chambers desolate’. Shops across England, Scotland and Wales closed.

Although such marks of respect might be expected now, that had not been the case in the early part of George III’s reign – or in respect of his immediate predecessors. Since Charles II, the monarchy had not enjoyed unalloyed popularity, especially with radical politics gaining ground.

Although such marks of respect might be expected now, that had not been the case in the early part of George III’s reign – or in respect of his immediate predecessors. Since Charles II, the monarchy had not enjoyed unalloyed popularity, especially with radical politics gaining ground.

According to Professor Colley’s article, ‘Ever since the passing of that immediate euphoria which greeted the Restoration, no English or British monarch other than perhaps Anne had achieved more than partial or transient popularity; no sovereign at all had been able to act as an unquestioned cynosure for national sentiment.’

So much had changed, though, that when George celebrated the beginning of his 50th year of kingship on 25 October 1809 – the first Golden Jubilee in 500 years. Lord Palmerston said, ‘Nothing could be better than its effect in London.'

In the course of George III’s reign, the view of the monarchy had changed. The main national anthem became ‘God save the King’, supplanting Rule Britannia. The State Coach was built, which was used at Her Majesty the Queen’s Coronation and will feature in this year's Platinum Jubilee procession. And a new focus on the monarch was used to distinguish patriotic British celebrations from those in revolutionary France.

Not all were convinced, as Professor Colley pointed out, Sir Francis Burdett claimed in the House of Commons that George Ill's jubilee was a "clumsy trick, to thrust joy down the throats of the people", in the wake of soaring food prices and other misfortunes[1].

But celebrations took place around the country and these were not always organised officially, with Napoleon in mind. Local authorities and individuals organised and led events nationally. And the Press was key in encouraging support, although what would today be called liberal elites criticised the celebrations.

According to Professor Colley, however, ‘The sheer scale of this event was a remarkable tribute to the activism of the press and, it would seem to public opinion which compelled many local authorities into action.’

According to Professor Colley, however, ‘The sheer scale of this event was a remarkable tribute to the activism of the press and, it would seem to public opinion which compelled many local authorities into action.’

At the same time, some of the other familiar activities around royal events developed - a thriving souvenir trade was established, Jubilee good works were encouraged, great crowds gathered to celebrate and sermons were preached.

During his reign, George III gradually became more popular in his own right. But the French Revolution, and the execution of the French monarch, would serve to cement his position as the father of the nation. These firmly established the British monarchy as the rallying point for patriotism - in contrast to the Revolutionary events in France and Napoleon’s 'adventures' across the Continent.

There were very real invasion scares in the early 1800s and the traditional Anglo-French rivalry came to be seen differently. By the time of his Golden Jubilee in 1809, the safety of the state was associated with the safety of the King.

With thanks to Dr Perry Gauci

[1] Professor Linda Colley: The Apotheosis of George III: Loyalty, Royalty and the British Nation 1760-1820. Pages 94-129 Past & Present, volume 102, Issue 1, February 1984.

‘Digitisation is revolutionising research,’ says Professor Chris Howgego, Keeper of the Ashmolean Museum’s Heberden Coin Room, which celebrates its Centenary this year.

Chris Howgego

Chris HowgegoPutting objects online is not just a nice-to-have, the Ashmolean’s curators insist, (although it is that). Digitisation is going to transform scholarship, adds Richard Ovenden, the head of Oxford’s Galleries, Libraries and Museums and the 25th incumbent as Bodley’s Librarian.

Digitisation is revolutionising research...Digitisation makes ‘big data’ research possible in the Humanities

Professor Chris Howgego

In terms of money, in particular, the implications could be far-reaching, Professor Howgego says. Not only will it will allow access to currently unseen objects – but more importantly it will also raise new questions and enable new methodologies, throwing a different light on past civilisations and societies, he explains.

With international collections and coin finds being put online, it will be possible for researchers to look in new ways at patterns of behaviour in the past and to work with other institutions to gain a much greater understanding of the ancient world. He says, ‘Digitisation makes ‘big data’ research possible in the Humanities.’

Although much focus on ancient coins comes from newspaper reports of sums raised, when finds are sold at auction, money provides a window into earlier cultures and societies. Professor Howgego’s enthusiasm for the subject is palpable.

If it were needed, the Ashmolean Museum’s 300,000 piece historic monetary collection, is proof positive that you cannot take it with you. It contains items from around the world, which have survived their owners by hundreds, if not thousands, of year. Made up of medals, bank notes and coins (some dating back to before 600 BC) the collection includes original Ming dynasty paper money, and some of the earliest coins ever minted, as well as golden hoards, buried in Oxfordshire, whose owners never returned to claim them.

It's history in your hand

Professor Howgego

The Ashmolean Museum’s 300,000 piece historic monetary collection is proof you cannot take it with you. It contains items from around the world, which have survived their owners by hundreds, if not thousands, of year

As crypto currencies around the world take a slide, leading many to question what is money, the Ashmolean team is in no doubt of the importance of the collection of which they are custodians.

‘It’s history in your hand,’ says Professor Howgego, of a coronation medal made for the accession of the boy King, Edward VI – and of a Roman gold coin thought to have been minted from gold looted from the Temple in Jerusalem.

Clearly proud of the collection and the research taking place in Oxford, Professor Howgego reveals there has been a new (2,000-year-old) acquisition for the Ashmolean. It is an unparalleled collection of 1085 gold and silver coins of the Iceni (Boudicca’s tribe): some of these tiny, impossibly brilliant coins, astonishing survivors from late Iron-Age Britain are in a special display in the Money Gallery, shining two millennia after its owners were dead and buried. And these are just a fraction of the historic coins on display and in the Museum’s secure vault behind the scenes.

Oxford’s Ashmolean, the oldest public museum in the world, is home to one of the world’s leading collections of ancient money. It is a resource for academics and experts, increasingly globally, now the collection is being made available online.

A coronation medal made for the accession of the boy King, Edward VI

A coronation medal made for the accession of the boy King, Edward VI

Of the 300,000 items, a third have already been digitised, thanks to the efforts of volunteers in OxfordDr Jerome Mairat

The Ashmolean’s collection may be worth a fortune but, says curator Dr Shailendra Bhandare, its real value is as a record of the past. He explains, money has been made of metal, stone, shells, cloth and even rice – whatever is of value to the society. And the coins and notes tell much about the societies which created them, the development of the civilisations and trade – and war.

One of the ‘highlights of the collection, is the Oxford crown, struck during the English Civil War, in Oxford’s brief time as Charles I’s capital city. There are only about ten in existence, and two are in the Ashmolean. They were made in a mint in New Inn Hall Street.

Meanwhile, a new Roman emperor was discovered, found in hoard at Chalgrove, only 12 miles away.

‘They were dancing the conga at the British Museum when it was identified,’ recalls Professor Howgego. The curator who discovered it said it was so surprising that ‘It was like flicking through a pack of cards and finding an 11 of clubs.’

The Ashmolean’s collection may be worth a fortune but its real value is as a record of the past

Dr Shailendra Bhandare

The coins themselves were often designed as records, rather than just being of monetary value, says Professor Howgego – used by rulers to put their stamp, quite literally, on history. From the images of short-lived Roman emperors, to pictures of Noah’s Ark, coins have been used to make statements – and not just in terms of the legality of tender.

The Coin Hoards of the Roman Empire Project, based in the Ashmolean, leads a collaborative international effort to preserve digitally this compelling form of national heritage. It has currently put online over 16,000 hoards containing a staggering eight million coins. The Roman coins that turn up today across Europe and Asia reveal the integrated nature of the Roman Empire – and its impact on neighbouring civilisations, such as India, where huge numbers of Roman coins have been found.

An Oxford Crown

An Oxford Crown

You couldn’t buy a loaf of bread with one of the coins...It could be worth a week’s earnings

Professor Andrew Meadows

It is thought the earliest coins were created by rulers to pay soldiers to fight in wars

He says, we already know the first coins emerged in the Greek province of Lydia in what is now Turkey. But the coinage was not then, he explains, about facilitating trade and coins were not used by most people.

‘You couldn’t buy a loaf of bread with one of the coins,’ he says, holding a chunky gold piece. ‘It could be worth a week’s earnings.’

It is thought, he says, coins were created by rulers in order to pay soldiers to fight in wars, rather than to facilitate trade – although they did that as well.

Digitisation of ‘history in your hand’ is set to transform research.

Jacqueline Pumphrey, April 2022

In his 1953 poem Days, Philip Larkin asks: ‘What are days for? Where can we live but days?’ He goes on with typical gloomy yet endearing angst: ‘Ah, solving that question/Brings the priest and the doctor/In their long coats/Running over the fields.’

Larkin would have done well to include ‘scientist’ along with priest and doctor. More specifically, he might have been interested to talk to circadian neuroscientists, such as Professor Russell Foster, who has said that the commercialisation of electric light since the 1950s has allowed us to ‘declare war upon the night’ and think that we can ‘do what we want, at whatever time we choose’.

Russell argues that in doing so, ‘we have thrown away an essential part of our biology’. One recent example of this can be found in Samsung’s ‘Night Owl’ television advertisement, which features a woman jogging through a city in the middle of the night (2.00am), tracking her progress with a Galaxy Watch. The advert encourages viewers to pursue their health and wellness goals on their own schedules – despite the overwhelming objective scientific evidence that this can be extremely harmful.

It is this insight about our arrogant 24/7 society that underpins Russell’s new book, Life Time, published by Penguin on 19 May. Almost a handbook, Life Time presents the reader with a wealth of information on what scientists have discovered about sleep and biological circadian rhythms. The book is designed to help each of us ‘make an informed and evidence-based decisions about improving our sleep and circadian health to improve our lives.’ Life Time represents a generous sharing of a lifetime’s work, and demonstrates Russell’s commitment to the public understanding of science.

Russell Foster is perhaps best known for his team’s contribution to the discovery in the late 1990s of photosensitive retinal ganglion cells, a type of neuron in the eye. Unlike the eye’s rod and cone cells, they’re not responsible for forming images, but for detecting light, providing information to the brain about the length of day and length of night. The ground-breaking discovery of these cells and their function was a milestone in the now exploding field of circadian biology to which Russell has dedicated his working life.

Photosensitive retinal ganglion cells are important because they help to ensure that the human body’s circadian system, which is organised by a master ‘body clock’ in the brain, is kept in synchronisation with external light and dark. Without this mechanism, our rhythms would drift out of sync, leading to all sorts of problems. We are biological animals whose organs need to be ready during the active phase of the day to eat and process food, and during the resting phase to use stored energy to repair tissue, remove toxins, fight off infection, form memories, and generate new ideas.

Russell’s interest in circadian rhythms is intertwined with his interest in the purpose and mechanisms of sleep, which led him to set up the Sir Jules Thorn Sleep and Circadian Neuroscience Institute at the University of Oxford in 2012. Scientists here are uncovering more about the fundamental ancient processes that govern time in our lives. They are investigating what happens when sleep and circadian rhythms are disrupted, for example in shift workers, or in those of us who think we can somehow live outside days, pushing our waking hours into the night. Being out of sync can lead to increased stress hormones, heart disease, weight abnormalities, reduced immunity, increased risk of cancer, and emotional and cognitive problems. No wonder Russell was motivated to share some of the cutting-edge insights from the scientific community in order to help people make good decisions about how to live healthy lives.

So what are the practical take-home messages of this book? Perhaps the most surprising one is that there is no ‘one size fits all’ in terms of sleep. It’s not helpful to think that everyone should be aiming for eight hours sleep a night, for example, or even that the holy grail is to sleep right through the night without waking up. The sleep that you need is linked to your genetics and environment and can change over the course of your life. The book includes pointers for how to determine your own ‘chronotype’ – do you function best in the morning, the evening, or in between? Armed with this information you can adapt your behaviour to synchronise your internal clock to external time in the best way for you.

There are specific messages about the best time for various health interventions: stroke medications such as aspirin should be taken before you go to sleep rather than in the morning, because aspirin turns-off the “stickiness” of platelets which are made at night; a flu vaccine is better given in the morning because the immune system is upregulated during the daytime. Russell explains the scientific evidence for behaviours that will improve our sleep, such as not drinking caffeinated drinks after lunchtime, and not eating a large meal or discussing potentially difficult issues immediately before bedtime.

The advice in this book is not delivered in a didactic fashion by an aloof expert from the hallowed halls of academia, but by an engaging and entertaining human being who is clearly excited by knowledge and passionate about sharing it. Academics are used to writing, spending long hours documenting the methodology and results of their experiments, and writing applications to persuade funding bodies to provide grants to allow that research to continue. But only a few are motivated or skilled enough to write about the insights of their work for the benefit of ordinary people who want to live their lives to the full.

Russell has clearly enjoyed digging deep into the topic that has fascinated him for his whole life, and then distilling the findings and making them accessible and relevant. His vast experience of giving public talks has enabled him to get inside the minds of his audience, and he has used genuine questions from people attending such events to form the basis of the wide-ranging and sometimes quirky Q&A sections at the end of each chapter. This book demonstrates the most practical purpose of the scientific endeavour – to apply the lessons learned in order to improve our everyday lives.

To return to Philip Larkin and what days are for, let us leave the answer to Russell, whose hope for his book is that it can help us to ‘be healthier, more creative, make better decisions, gain more from the company of others, and view the world and all that it has to offer with a greater sense of curiosity and wonder’.

Patient recruitment is on-track in the Oxford-led DeTACT trial of safe, effective drug combinations to prevent the spread of artemisinin and multi-drug resistant malaria in Africa.

The global fight against malaria is at a critical point. Overall progress has now stalled and even worsened in some countries in Africa, where most of the world’s 627,000 deaths from malaria occurred in 2020.

The situation is becoming grave with recent studies confirming the growing prevalence in Rwanda and Uganda of P. falciparum malaria parasites partially resistant to artemisinins, which are the most important frontline anti-malaria drugs.

No new antimalarial drugs are expected in the near future. If multi-drug resistant falciparum malaria becomes established in East Africa and spreads to other parts of Africa, it is soon likely to compromise the efficacy of artemisinin-based combination therapies or ACTs — putting millions of Africans at risk of drug-resistant malaria infection and death.

The WHO has said this 'independent emergence of artemisinin partial resistance in the African Region is of great global concern.'

One possible solution — new drug combinations with artemisinins and two other frequently used antimalarial drugs (Triple ACTs or TACTs) — was found in 2020 by the large multi-centre, multi-country TRAC2 study to be highly efficacious even in places where ACTs were failing.

Before TACTs could be widely deployed to control artemisinin-resistance in Africa, however, their efficacy, safety and tolerability would first need to be confirmed in African populations, especially children.

A child suspected to have malaria being screened for recruitment into the DeTACT Trial at the Centre National de Formation et de Recherche en Santé Rurale (CNFRSR), Maférinyah, Guinea. © MORU. Photographer: Mehul Dhorda.

A child suspected to have malaria being screened for recruitment into the DeTACT Trial at the Centre National de Formation et de Recherche en Santé Rurale (CNFRSR), Maférinyah, Guinea. © MORU. Photographer: Mehul Dhorda.Led by University of Oxford-affiliated researchers based in Bangkok at the Mahidol-Oxford Tropical Medicine Research Unit (MORU), the Developing Triple Artemisinin-based Combination Therapies (DeTACT) trial is currently studying in eight African and three Asian countries two new TACTs to generate evidence that they are effective first-line malaria treatments and support their deployment in Africa to prevent or delay the emergence of artemisinin and multi-drug resistant malaria in Africa.

Funded by UKaid administered through the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO), DeTACT’s goals are ambitious.

'The emergence of artemisinin resistance in Africa is a serious concern, and its containment is paramount to avoid treatment failures in falciparum malaria in the future. TACTs can be an important contribution to this, both by delaying antimalarial drug resistance to the existing drugs, and by providing an effective treatment for multidrug resistant infections. DeTACT will provide the necessary evidence on TACTs, deliver a product that can be deployed, and will engage with national and global policy makers and other stakeholders to discuss the potential position of TACTs in the mix of antimalarial drugs,' says Professor Arjen Dondorp, the Principal Investigator of the DeTACT.

Besides comparing two existing ACTs (artemether-lumefantrine and artesunate-mefloquine) against two TACTs constituted of one additional drug added to each of these combinations (amodiaquine and piperaquine, respectively), DeTACT is conducting studies to forecast the impact of TACTs on controlling the spread or emergence of multidrug-resistant falciparum malaria leading to its elimination, and to examine the market readiness and ethical considerations of using TACTs across the malaria endemic world.

'The DeTACT Project includes modelling studies that will project the impact and cost-effectiveness of TACTs in preventing the spread of artemisinin resistance, explained Dr Chanaki Amaratunga, DeTACT Project Coordinator.'

'We are also conducting studies with all malaria stakeholders, starting from patients to researchers and policy makers, to elucidate the ethical and market aspects of their deployment. Along with the clinical trial, these studies constitute a comprehensive assessment of the expected advantages and potential barriers to the large scale use of TACTs,' said Dr Amaratunga.

Despite disruptions caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, DeTACT has already recruited over 700 patients, and aims to complete the recruitment of close to 4000 patients by early 2023.

The modelling, ethics and market positioning studies are well advanced and are expected to be completed by the end of 2022.

In addition, MORU has signed a memorandum of understanding with Fosun Pharma and Medicines for Malaria Venture (MMV) to collaborate with them to develop and pre-qualify fixed-dose combinations of TACTs prior to marketing them across Africa and the malaria endemic world.

'The DeTACT Trial will generate data not only on the efficacy and safety of TACTs but also on the pharmacokinetics of each of the drug components, including in malnourished children – a particularly vulnerable sub-population. In addition, there will be cutting-edge analyses, combining clinical trial data with that from whole genome and transcriptome studies, to improve our understanding of artemisinin and other antimalarial drug resistance,' said DeTACT-Africa Coordinator Dr Mehul Dhorda.

'We sincerely thank our partners conducting the field trials for maintaining their commitment to completing the trial in a difficult context,' Dr Dhorda added.

DeTACT is the third of three FCDO-supported multi-country, multi-site trials (TRAC and TRAC2) that have characterised artemisinin resistance and tested multi-drug resistant malaria treatments in South-East Asia. The work related to pharmacokinetics of antimalarials in malnourished children is supported by a grant from the Wellcome Trust.

- ‹ previous

- 8 of 246

- next ›

Can we truly align AI with human values? - Q&A with Brian Christian

Can we truly align AI with human values? - Q&A with Brian Christian  Entering the quantum era

Entering the quantum era Can AI be a force for inclusion?

Can AI be a force for inclusion? AI, automation in the home and its impact on women

AI, automation in the home and its impact on women Inside an Oxford tutorial at the Museum of Natural History

Inside an Oxford tutorial at the Museum of Natural History  Oxford spinout Brainomix is revolutionising stroke care through AI

Oxford spinout Brainomix is revolutionising stroke care through AI Oxford’s first Astrophoria Foundation Year students share their experiences

Oxford’s first Astrophoria Foundation Year students share their experiences DPhil student, Frankco Harris, reflects on his unique journey to Oxford and future plans

DPhil student, Frankco Harris, reflects on his unique journey to Oxford and future plans Oxford undergraduates reflect on their first term

Oxford undergraduates reflect on their first term Unlocking more sustainable futures with green chemistry

Unlocking more sustainable futures with green chemistry