Features

Dr Manuel Anglada Tort. Image credit: University of Oxford.

Dr Manuel Anglada Tort. Image credit: University of Oxford.

Please could you introduce your work?

I am interested in exploring the psychological and cultural foundations of music, and the role they play in human societies and cultural evolution. Music has not evolved from individual brains but instead from being embedded in large cultural processes of multiple social interactions. To understand why music is the way it is, and how we find pleasure in it, we therefore need to consider the collective processes by which music has evolved. To study this, my work combines methods from many different disciplines, including psychology, computer science, musicology, and cultural evolution.

For example, I use singing as a model to study how music evolves when it is transmitted across human generations. Singing is fascinating because it is the most widespread mode of musical expression, practiced by all cultures and ages, even in infants. We developed a novel method to simulate the evolution of music with singing experiments, where sung melodies are passed from one singer to the next, similar to the popular ‘telephone game.’ Using this method, we examine how thousands of musical melodies change and evolve as they are orally transmitted across participants.

What have you found so far?

We found that oral transmission has profound effects on how melodies evolve, shaping initially random sounds into more structured musical systems that increasingly reuse and combine fewer elements, such as certain pitch intervals and simple melodic contours (the sequence of ups and downs in pitch). This ultimately makes the melodies easier to learn and transmit over time. Importantly, the structural features that emerged artificially from our experiments are largely consistent with widespread melodic features found in most musical traditions across the world. This suggests that ‘human transmission biases’ in singing may contribute, at least partly, to the observed cross-cultural commonalities found in many music cultures across the world.

The next stage is to work out which factors are responsible for these ‘transmission biases.’ Our experiments show that physical and cognitive constraints in our capacity to produce and process music are of critical importance. For example, melodies that are hard to sing or remember are systematically less likely to survive the transmission process. We also found that participants’ previous cultural exposure is important. For instance, in a group of US participants, the ‘evolved’ melodies tended to align with certain cultural conventions of Western music, whilst a group of participants from India showed cross-cultural divergences.

Overall, this work is exciting because allows us to study evolutionary processes that are typically hidden or very hard to measure. We are excited to extend this work to study other production modalities, such as speech, as well as to test participants from more diverse musical backgrounds.

Online iterated singing method, developed by Manuel to study how oral transmission affects the evolution of melodies in songs. Participants hear a sequence of tones generated by a computer and reproduce it by singing back. The vocal reproductions are analysed by a computer and played to the next participant as the input melody. This process is repeated with many parallel transmission chains at the same time, each corresponding to a melody evolving over 10 generations. Image credit: Manuel Anglada Tort.

We talk of the culture of music but essentially, music is culture. Just as we cannot understand culture by only looking at individual brains, we cannot understand music without considering the larger cultural and social processes surrounding it.

For your PhD at the Technical University of Berlin, you studied how behavioural economics can be applied to music cognition. What did you find?

Behavioural economics recognises that human beings do not always think through every decision rationally. For example, we often rely on cognitive heuristics to simplify complex decisions: mental shortcuts that allow us to use information selectively and effectively.

In my PhD, I showed that, when it comes to music decisions and preferences, the context in which music is presented has a very important influence. Our preferences for music will change dramatically depending on the time and day of the week, which activity we do while listening to music, whether we are alone or with others, and what information we know about the artists’ skills and persona. Even small variations on the title of a song can have an important impact on how much people like the music.

In one experiment, we showed that contextual factors can completely change our experience of the same piece of music. We told participants to listen to ‘different’ musical performances of an original piece when in fact they were exposed to the same repeated recording three times. Each time, the recording was accompanied by a different text providing information about the supposed performer, which was manipulated to indicate either low or high prestige of the performer. We found that most participants (75%) believed that they had heard different musical performances. Interestingly, participants evaluated identical recordings more positively in terms of liking and music quality when they thought the music was performed by a professional musician rather than a less-skilled musician. This suggests that when we judge music, we rely on cognitive biases and heuristics that do not always depend on what we actually hear.

The results of our studies suggest that when we judge music, we rely on cognitive biases and heuristics that do not always depend on what we actually hear.

You have also worked as a science consultant for an audio branding firm. What exactly does audio branding involve?

Audio branding is where brands translate their identity and values into audible elements that are then repeated in their advertisements or used within their products. As we are increasingly saturated with visual information, companies are showing a growing interest in using audio branding to reach target audiences. For example, repeated catchy melodies of three to five notes can be highly effective in making people recognise a brand or product, such as the iconic audio logos of McDonald’s or Netflix. As researchers, we can quantify the effectiveness of different music when paired with certain commercials or brands, for example by measuring the impact of music on consumers’ brand recognition or purchase intention.

In one study, we found that pairing brands with music that can be recognized by the target consumers increased brand choice by 6%. Although this is a small effect, it is quite remarkable given that using music is relatively easy and cheap for brands. But the use of advertising music is becoming much more sophisticated with AI and big data. The future of music and advertising is about creating individualised consumer experiences where the same ads and products can be paired with different music targeting the many individual preferences of consumers.

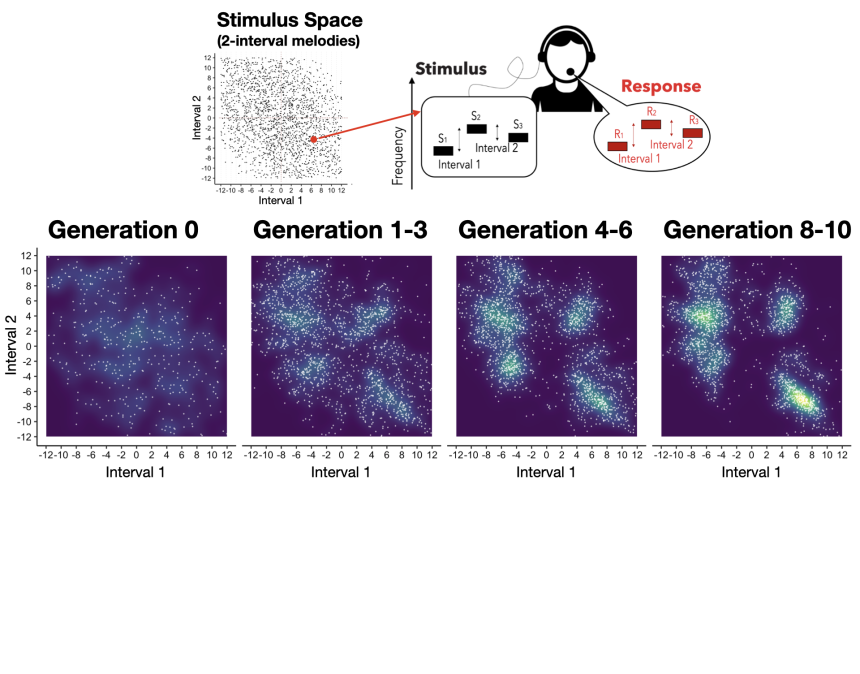

Oral transmission effects on melodies. The entire stimulus space of three-note melodies (two intervals) can be defined along two continuous dimensions, one for each interval in the melody (with each dot representing a melody). At the start of the experiment (Generation 0), hundreds of melodies were randomly sampled from this space. These melodies were then played to participants, who were asked to reproduce them by singing. Over time, oral transmission shaped initially random melodies into more structured and simplified musical systems. By the end of the experiment (Generation 8-10), melodies were concentrated in few locations, displaying a rich structure that is consistent with Western discrete scale systems. Image credit: Manuel Anglada Tort.

Oral transmission effects on melodies. The entire stimulus space of three-note melodies (two intervals) can be defined along two continuous dimensions, one for each interval in the melody (with each dot representing a melody). At the start of the experiment (Generation 0), hundreds of melodies were randomly sampled from this space. These melodies were then played to participants, who were asked to reproduce them by singing. Over time, oral transmission shaped initially random melodies into more structured and simplified musical systems. By the end of the experiment (Generation 8-10), melodies were concentrated in few locations, displaying a rich structure that is consistent with Western discrete scale systems. Image credit: Manuel Anglada Tort.Music is essentially a psychological phenomenon: our mind has evolved to translate physical qualities of sound into the subjective experience of music.

How did you get in to music psychology?

I have always loved playing and composing music, but my academic career originally started in psycholinguistics and experimental psychology, studying the bilingual brain. I then happened to find out about this small research field in music psychology. For me, music and science seemed the perfect combination, so I applied to Goldsmiths, University of London, to study their MSc in Music, Mind and Brain.

It was revolutionary for me to realise that all the scientific methods I had learnt for experimental psychology could be applied to study music as well; working out how we perceive sound and get pleasure from it, and the many psychological functions that music making and listening have. I remember the lectures on psychoacoustics to be particularly inspiring, where I learnt that music is essentially a psychological phenomenon: our mind has evolved to translate physical qualities of sound into the subjective experience of music. For example, we perceive pitch from the speed at which an object vibrates: the faster the vibration, the higher our perception of pitch. By combining different sets of music pitches, we can in theory create infinite music patterns. Some of these patterns will become popular in a given population, whereas others will die out.

I feel very fortunate that this work is a fusion of three key interests of mine: science, music and culture.

What plans do you have for the Music, Culture, and Cognition group in the near future?

I am excited about the potential of this group, and I feel very fortunate to have an incredible network of international collaborators with expertise in music cognition and cultural evolution. The idea is to continue to perform cutting-edge research on the intersection between music, culture, and cognitive science here at the University of Oxford. This will include continuing our experiments to simulate cultural evolution (such as the singing transmission study) and extending these methods to also study more complex cultural phenomena. For example, to study how the evolution of musical structures may depend on selection pressures (e.g. composers vs critics vs consumers) or underlying population structures, such as social networks and their different patterns of connectivity.

Another exciting line of research is on the topic of cultural globalization and popularity dynamics: exploring how songs spread across the world and what determines whether a song will become a global hit or not (also known as ‘Hit Song Science’). Traditionally, people have attempted to predict music success based only on the content of the music: its harmony, timbre, or rhythm. But studies have repeatedly failed to predict musical success based on musical features alone. I believe that the distribution network by which music spreads within and across countries may help solve this puzzle. So, we are investigating ways to measure and quantify this underlying network of music diffusion and its impact on cultural globalization.

You arrived here less than two months ago – what do you make of Oxford so far?

Oxford is an incredible place and I feel very privileged to be here. Unlike ‘campus’ universities, you feel that the whole city itself is the university; you sense it all around you. The musical scene is excellent (which is important to me) and more generally, it feels that this is a place where anything you might want to do is possible – from life drawing, to dancing, to playing any kind of instrument. I have already found a group of friends to go rock climbing with and recently got into bird watching for the first time. I have also fallen in love a bit with the English pub culture. Coming from Spain, I had never seen anything like them before, and am fascinated by how they are all so different and have so much history. I am looking forward to exploring all the ones in Oxford over time!

You can read Dr Manuel Anglada Tort's latest research paper 'Large-scale iterated singing experiments reveal oral transmission mechanisms underlying music evolution' in the journal Current Biology.

In the video below, Manuel Anglada Tort describes his work to study the effect of oral transmission on music evolution using online singing experiments, in an event for the Oxford Seminar in the Psychology of Music.

Tatjana Gibbons, a DPhil student at Oxford’s Nuffield Department of Women's & Reproductive Health, talks about research to develop a new 20-minute diagnostic test for endometriosis.

Around one in ten women will develop some form of endometriosis in their lives, a disease that affects more than 190 million women worldwide.

Yet despite its common occurrence, it typically takes eight years for a diagnosis – a figure that has shown no sign of improving in the past decade. The problem is that it typically involves several visits to the GP and hospital referrals, multiple scans and often surgery to diagnose.

Not only does this leave patients suffering for a significant period of time, but it can also require unpleasant and invasive procedures.

Aside from the pain, discomfort and worry about an ongoing undiagnosed condition, an important issue is its effect on fertility when left unchecked. A national questionnaire we conducted with over 1000 respondents with confirmed or suspected endometriosis found that 88% of respondents had experienced a delay in diagnosis, and 72% felt that an earlier diagnosis would have changed their life choices with regard to decisions such as fertility planning. With earlier diagnosis, it is possible to treat both the pain and discomfort as well as to begin to consider fertility options such as freezing eggs for the future.

The problem with diagnosing endometriosis is that small lesions in the pelvis are not detected on ultrasound and often need surgery to detect. This is why we are assessing alternative ways of looking inside the body without being invasive.

Our research group is conducting the DETECT (Detecting Endometriosis expressed inTEgrins using teChneTium-99m) imaging study, to investigate whether an experimental image marker (⁹⁹ᵐTc-maraciclatide) that binds to areas of inflammation can be used to visualise endometriosis using a 20-minute scan. In endometriosis, small parts of the lining of the uterus – the endometrium – are found in the fallopian tubes, ovaries or in the pelvis (for example, attached to bowel). The presence of the endometrium outside of the uterus leads to inflammation in the pelvis, which this test will aim to highlight.

If this is successful, it will give us a fast and effective way to identify any case of endometriosis, as well as assessing how serious the patient’s individual condition is and may even be able to distinguish between old and new disease.

Professor Christian Becker, who is Co-Director of the Endometriosis CaRe Centre in Oxford together with Professor Krina Zondervan, Head of Department at the Nuffield Department of Women’s and Reproductive Health, University of Oxford, will lead this initial study on women due to have planned surgery for suspected endometriosis.

Two to seven days before their operation, the participants will be invited for an imaging scan which will compare the suspected locations of disease detected on the scan and in surgery to confirm whether this imaging test matches what is found.

The beauty of this approach is that, if successful, it will provide a quick, painless and affordable option for tens of millions of women worldwide.

To read more about this research project and the partners involved, please visit https://www.wrh.ox.ac.uk/news/new-imaging-study-could-make-diagnosing-endometriosis-quicker-more-accurate-and-reduce-the-need-for-invasive-surgery

The study is being carried out in partnership with Serac Healthcare, a UK-based developer of breakthrough imaging technology.

Professor Sarosh Irani of the Nuffield Department of Clinical Neurosciences

Today – Wednesday, 22 February – is World Encephalitis Day.

Encephalitis is a brain condition which I have encountered many times throughout my career, witnessing first-hand the devastating impact that it can have on patients and their family and friends.

My team in Oxford work to improve the diagnosis, treatment and after-care for patients with autoimmune forms of encephalitis. Discoveries to improve patient care is what drives everyone in my research group and clinic, and is what led me to become a member of the Encephalitis Society’s Scientific Advisory Panel.

Our work has focused on the autoimmune forms of encephalitis, where one’s own immune system attacks the brain in error, leading to brain swelling. We work hard, with our patients and their carers, to better understand diagnosis, the underlying cause of the diseases and patient outcomes. We have over 150 publications in this area, and aim to produce many more over the next few years.

Another key aspect of my work is improving awareness of encephalitis among the general public and fellow healthcare professionals in the hope that it can eventually lead to a quicker pathway for patients to get the care they need.

Shockingly, a YouGov poll commissioned by the Encephalitis Society has found that around 8 out of 10 people do not know what encephalitis is, which is why I would like you to spare a few moments and read the following facts:

1. Encephalitis is an inflammation of the brain

2. It is caused by an infection or through the immune system attacking the brain in error

3. Anyone can be affected by encephalitis, irrespective of age, gender or ethnicity

4. It can have a high death rate and survivors might be left with an acquired brain injury and life-changing consequences

5. In some cases, encephalitis can impact mental health, causing difficult to deal with emotions and behaviours, and can lead to thoughts of self-harm and even suicide

To add our support to this very important day on the calendar, my colleagues and I have been wearing red today as part of the Encephalitis Society’s #Red4WED social media campaign and, this evening, I am delighted to say that the University of Oxford’s Ashmolean Museum will be among 200 global landmarks, including Niagara Falls, Piccadilly Lights, and the CN Tower in Toronto, lighting up red for World Encephalitis Day.

Finally, if you are a social media user, I urge you to take some time this evening and search for the hashtags #WorldEncephalitisDay, #Red4WED and #encephalitis for a wonderful example of what can be achieved when a community comes together with a special goal in mind – to shine a light on encephalitis.

For more information, visit www.worldencephalitisday.org

Dr Elsa Panciroli during fieldwork on the Isle of Skye. Credit: Elsa Panciroli/Davide Foffa

Dr Elsa Panciroli during fieldwork on the Isle of Skye. Credit: Elsa Panciroli/Davide Foffa

I am a palaeontologist who uses X-ray tomography and digital visualisation to understand the anatomy and growth of the first mammals and their closest relatives. My work focuses on mammals from the Mesozoic, the era of Earth’s history lasting from about 252 to 66 million years ago, comprising the Triassic, Jurassic, and Cretaceous Periods.

Of course, this includes giant dinosaurs, but it is also when the foundations were laid down for all the modern groups of animal life, including mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians, and lizards.

People often assume mammals only appeared after the asteroid wiped out the non-bird dinosaurs, but that is not the case. Mammals appeared in the Triassic, at the same time as the dinosaurs, they were diverse and exploited a variety of different ecological niches. The group to which mammals belong stretches back even further in time, and is much more exciting than most people realise.

In traditional school text books, the dinosaurs are shown as the dominant species and the mammals as tiny things, almost an afterthought, scurrying away in the background. But these early mammals were actually highly successful?

Yes indeed – mammals may have been small during the Mesozoic but they were undeniably successful little animals. Many were insect-eaters, but there were also herbivores and carnivores. They were playing a fundamental role in the wider ecosystem. Some could glide like flying squirrels, others could dig like moles or were semi-aquatic. Furthermore, they were also doing something really exciting by forming a new, unique type of organism: one with warm-blood and fur that gave birth to live young. This had never been done before.

You have carried out a lot of fieldwork on the Isle of Skye. What makes this site so special?

The Kilmaluag Formation on the Isle of Skye, Scotland, provides one of the richest Mesozoic vertebrate fossil assemblages in the UK, and is emerging as one of the most important globally for Middle Jurassic tetrapods. It compares with localities such as Morrison Formation in North America, or the Yanliao Biota in China. Fewer species have been found on Skye, but they are exceptionally complete and well preserved. I have been doing fieldwork there since 2016, but I grew up in the Highlands and Islands, so the area is very special for me. As someone who loves the mountains, being able to work in sight of the Cuillin always feels special.

What is it like doing fieldwork there?

I mainly work on the southern part of the island, where rocks from the Middle Jurassic are exposed on the seashore and eroded very slowly by the waves. Normally we only have time to visit one site each day and this will be dictated by the tide times. The area is a Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI), as well as falling under Scotland’s new Nature Conservation Order (NCO) designation, for its geology, including fossils.

We do not just collect anything on the off-chance it contains a fossil. We make a judgement call on which rocks look the most promising, and only collect those. Usually, only a tiny fragment of fossil is visible on the rock surface and it is often obscured by seaweed and limpets. So it can be hard to tell how much more may be hidden inside.

Tell us about your work at the Oxford University Museum of Natural History (OUMNH)

The OUMNH has an impressive collection of Mesozoic mammal fossils collected locally at Stonesfield and at Kirtlington. They come from the same age rocks as Skye, so I use them to compare with the new Scottish fossils we find. The Stonesfield specimens are the first Mesozoic mammals fossils ever identified, back in the early 19th Century, making them historically important as well as scientifically invaluable. The specimens from Stonesfield are almost entirely individual teeth – no bigger than grains of cous cous. But we can still work out an incredible amount from these, especially using new techniques such as synchrotron scanning to examine the microstructure. From this we can work out their age and how quickly they grew.

Tell us about your book Beasts Before Us - The Untold Story of Mammal Origins and Evolution. How did that come about?

Most books about mammalian evolution start at the end of the Cretaceous, but their evolution stretches right back over 300 million years. I write about the incredible creatures related to mammals that lived long before the dinosaurs. The book also tells untold human tales; of indigenous people who knew about these fossils long before European settlers appeared, and pioneering female scientists who ought to be household names.

I first started writing about these amazing things when I was a Masters student. Eventually, I realised I had more than enough material to write a book. I pulled together all my blogs, published articles and notes, then organised two months to write the book. Then there was a global pandemic… so I ended up with a lot of free time to finish the manuscript. It was published in June 2021, and the feedback has been so positive. I was so excited when The New York Times review called it ‘smart, passionate and seditious’ - I don’t think many books about fossils can claim to incite rebellion! It also led to lots of talks and outreach work.

Skull bones of the Jurassic mammal Borealestes serendipitus from the Isle of Skye. Credit: Elsa Panciroli

Skull bones of the Jurassic mammal Borealestes serendipitus from the Isle of Skye. Credit: Elsa PanciroliAnd you have a new book out too?

Yes, The Earth: A Biography of Life came out in April 2022. It uses a series of different organisms – including plants, single-celled organisms and animals – to take you through the great events and evolutionary innovations in earth’s history. It is very visual too, with stunning illustrations, including some by the talented palaeoartist Grace Varnham. There are so many amazing stories in evolutionary research I could write a book every year and I still would not tell everything. The book has inspired the upcoming exhibition Connected Planet at the University of Oxford Museum of Natural History; it will explore the oceans, land, and air around us to witness this dynamic connection and see what happens when the balance tips.

You are also quite an artist…

I don’t think of myself as an artist, but I do enjoy creating visual interpretations of the fossil specimens we discover. The art world can be a bit dismissive about palaeoart, and it is sometimes portrayed as just drawing dinosaurs for children. But modern palaeoart is a dynamic and cutting-edge specialism that just happens to depict extinct animals.

Really good palaeoartists need to know a lot about the science of palaeontology, besides animal anatomy and behaviour. These artworks serve a really important purpose in acting as a bridge between scientists and the public.

Were you always interested in geology and ancient mammals?

As a child, I was absolutely fascinated by rocks and used to collect them everywhere I went. But, growing up in the rural highlands (my primary school only had about 15 pupils), I didn’t have access to libraries and museums and I couldn’t learn much about the science of geology, so I would just make up my own names for the rocks I collected. After finishing secondary school, I didn’t know what I wanted to study, so I just started working and did all sorts of jobs from working in garment factories to cleaning houses. I travelled to various countries and in my late 20s I realised the one thing that always interested me was the natural world. So I enrolled at the University of the Highlands and Islands as a mature student to study Environmental Sciences.

At first, I expected to go into conservation, but in one class we looked at palaeoclimatology, and that got me thinking about deep time and the study of rocks and fossils – stuff that was properly old, millions of years. And that was it, my course was set.

Palaeoart reconstruction of the Jurassic mammal Wareolestes rex. Artist: Elsa Panciroli

Palaeoart reconstruction of the Jurassic mammal Wareolestes rex. Artist: Elsa Panciroli

From there, I did an MSc in Palaeobiology at the University of Bristol, studying ankle bones in fossil mammals. The shape of the ankle is linked to how an animal moves, so I used them to predict whether a fossil species was a digger, a climber, and so on. It is amazing what you can tell about a species’ lifestyle from a single tiny bone.

In 2015 I started a PhD at National Museums Scotland on Scottish mammal fossils from the Middle Jurassic, which is when I started working on the Kilmaluag Formation on Skye. And I have pretty much continued this work up to today, joining Oxford University’s Department of Earth Sciences in 2019. I took up my current role as a Leverhulme Early Career Research Fellow at Oxford University Museum of Natural History in 2020.

What would the young Elsa think of your work now?

I think she would be amazed I was spending my time studying really cool fossils in Scotland. When I was a child, I always wished experts would visit our school and teach us more about rocks and fossils. Remembering this inspired me to create the Scottish Fossil Workshops programme, which was a two-hour workshop I created in 2019. It was specifically designed for primary schools in rural parts of Scotland – places that don’t usually get school visits because they are hard to get to, or don’t have very many pupils. I even returned to my own school.

What is next? Where do you see yourself in the future?

I am not the sort of person who makes 10 or even five year plans, I like to take opportunities as they come. I will definitely keep writing books, and I feel there are so many exciting niches within palaeontology and questions to ask, I could dedicate my entire career to answering them, funding permitting!

By Dr Louise Dalton and Dr Elizabeth Rapa of Oxford's Department of Psychiatry.

Every day, thousands of parents and grandparents are diagnosed with serious health conditions such as cancer, lung or heart disease. They are then faced with the unenviable task of sharing this information with the children they love.

Research has shown that effective communication with children about parental illness has long term benefits for children and their family’s physical and mental health. These include better child psychological well-being, as well as lower reported symptoms of depression, anxiety and behavioural problems. It also has benefits for parental mental health, adherence to treatment (such as following the prescribed drug regime) and family functioning.

However, adults find sharing a diagnosis with children one of the most difficult experiences. Understandably, they want to protect children from distress and many feel uncertain about whether children need to be told, or when and how to navigate these sensitive conversations. Yet, children are “astute observers” and are often acutely aware of changes within the family. Silence about what is happening risks children misinterpreting the situation and worrying alone, without access to the emotional support they need.

Previous research has found that patients want help from their clinical team to think about what, how and when to share their diagnosis with children, or how to answer questions such as “Are you going to die?” – but often report finding this support difficult to find. However, few studies have asked healthcare professionals about how they perceive their role regarding the needs of patients’ wider families. A team from the Department of Psychiatry interviewed 24 NHS clinicians from different professional backgrounds and working across a range of specialties to find out more about their views and experiences regarding the needs of patients’ children.

Our latest study, published in PLOS One, found that although patient’s family details were often recorded, this information was not routinely used to help patients share their diagnosis with children. In other situations, patients’ relationships with children were rarely or never identified.

The NHS healthcare professionals who took part reported feeling uncertain about asking patients about what children understand. They feared that they would make the situation worse or upset their patients.

“What can I say, what if they are in pieces, what do I do with that at that time of day? It seems a bit crass to enquire about something you aren’t in a position to help with.” GP

“Your worst fear is saying the wrong thing” Oncology

It was also frequently assumed that someone else in the clinical team would talk to the patient about their children, but often this meant opportunities for these conversations were missed.

“How that is dealt with, I am not really in the loop. […] So you don’t really know what happens to those children in terms of who says what to them. Someone might, but not me.” Surgery

Because you are talking to them [adult patient] directly, you tend to leave it to them to approach that [talking to their children]. Not that that is necessarily right, but it is the way it tends to happen.”

Others recognised their vital role and the importance of “thinking about the children and the family as whole” and being honest about the reality of the patient's situation.

“Don’t ever tell your child an untruth, don’t say ‘It’s all going to be fine, I am going to live forever’. Be truthful.” Neurology

While acknowledging the multiple demands on healthcare teams, the authors recommend a culture shift in recognising that talking to children about their parent's illness improves family relationships and mental health. Sharing patients’ desire for support from their clinical team around these issues may reassure healthcare professionals that initiating a conversation about children will be welcomed. Indeed, clinicians can play a key part in reassuring and guiding families to open up this sensitive topic with children. Working in partnership, healthcare professionals and families can protect the psychological well-being of children who are affected by the illness of an adult they love.

This is an important area to get right and a programme of research led by Dr Louise Dalton, Dr Elizabeth Rapa and Professor Alan Stein focusses on facilitating family centred conversations with clinical teams in every discipline. The team are currently developing a resource for all healthcare professionals to help them identify children who are important to their adult patients irrespective regardless of their patients’ diagnosis or age. This will be freely available to everyone and show professionals how four short steps during a consultation could have huge benefits for their patients and loved ones, with a lasting legacy for children’s psychological wellbeing.

The study, 'Exploring healthcare professionals’ beliefs, experiences and opinions of family-centred conversations when a parent has a serious illness: A qualitative study', can be read in PLOS One.

- ‹ previous

- 6 of 247

- next ›

From research to action: How the Young Lives project is helping to protect girls from child marriage

From research to action: How the Young Lives project is helping to protect girls from child marriage  Can we truly align AI with human values? - Q&A with Brian Christian

Can we truly align AI with human values? - Q&A with Brian Christian  Entering the quantum era

Entering the quantum era Can AI be a force for inclusion?

Can AI be a force for inclusion? AI, automation in the home and its impact on women

AI, automation in the home and its impact on women Inside an Oxford tutorial at the Museum of Natural History

Inside an Oxford tutorial at the Museum of Natural History  Oxford spinout Brainomix is revolutionising stroke care through AI

Oxford spinout Brainomix is revolutionising stroke care through AI Oxford’s first Astrophoria Foundation Year students share their experiences

Oxford’s first Astrophoria Foundation Year students share their experiences DPhil student, Frankco Harris, reflects on his unique journey to Oxford and future plans

DPhil student, Frankco Harris, reflects on his unique journey to Oxford and future plans Oxford undergraduates reflect on their first term

Oxford undergraduates reflect on their first term