Back to the Future: Oxford monograph is landmark in plant research

By Sarah Whitebloom

From Darwin to the present day, creating a monograph is at the heart of biological science. It takes years of painstaking effort and attention to detail to describe and log each and every species in a genus, producing an encyclopaedic guide – the monograph. It is taxonomy at its most taxing.

Large-scale monography is rarely undertaken today and is often seen as passé, dusty even, despite its undoubted value. Nevertheless, a team led by Professor Robert Scotland, of Oxford’s Department of Plant Sciences, has revived this time-honoured art by creating a landmark monograph of the genus Ipomoea. Better known as ‘Morning Glories’, the genus includes more than 800 different species, including the crop, sweet potato. And it is anything but dusty, blending traditional techniques with cutting-edge science to produce a massive monograph of 825 pages.

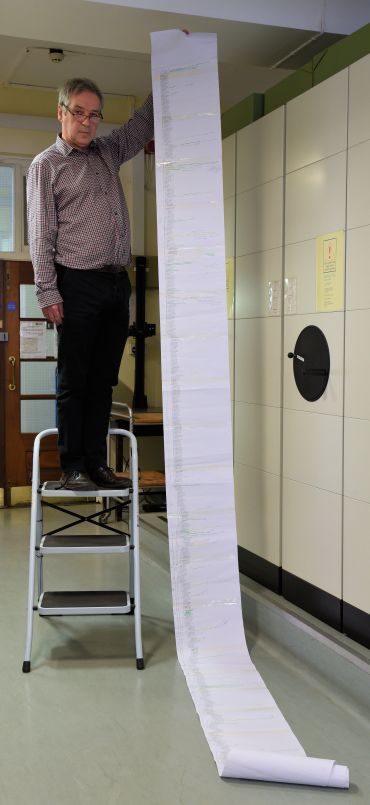

Professor Robert Scotland holding the Ipomoea family tree

Professor Robert Scotland holding the Ipomoea family treeAs part of the work, the team needed to identify specimens from around the world. Carrying out such a massive piece of research has taken the team of four more than five years, examining thousands of specimens from 80 different collections in Europe as well as from around the world.

The team has discovered 65 new species and have corrected numerous errors in the labelling of plant specimens in museum collections.

To date, the team has discovered 65 new species and have corrected numerous errors in the labelling of plant specimens in museum collections. They have challenged some long-held ideas cherished by botanists and anthropologists. They have created quite a stir in the South Pacific, because the monograph established that plants had travelled long distances over land and sea, without any human assistance – undermining assertions that the existence of sweet potatoes in Polynesia proved beyond doubt there must have been early contact between the Americas and islanders.

Why does this matter? Aside from the obvious academic uses of the monograph, John Wood, one of the monographs authors, says it has very real implications for the environment and for conservation.

How can you know the future of a plant, if you don’t know of its existence or its characteristics?

‘How can you know the future of a plant, if you don’t know of its existence or its characteristics?’ he asks. This is particularly important in the case of potential food crops, such as the wild relatives of the sweet potato, which is one of the top ten global food crops.

‘Insects and flowering plants are the two big powerhouses of global biodiversity,’ says another of the authors, Dr Pablo Munoz Rodriquez . ‘Yet for groups, such as Ipomoea, we haven’t even known what there is….and there’s no chance you can conserve something, if you don’t know what you’ve got.’