Features

Jacqueline Pumphrey, April 2022

In his 1953 poem Days, Philip Larkin asks: ‘What are days for? Where can we live but days?’ He goes on with typical gloomy yet endearing angst: ‘Ah, solving that question/Brings the priest and the doctor/In their long coats/Running over the fields.’

Larkin would have done well to include ‘scientist’ along with priest and doctor. More specifically, he might have been interested to talk to circadian neuroscientists, such as Professor Russell Foster, who has said that the commercialisation of electric light since the 1950s has allowed us to ‘declare war upon the night’ and think that we can ‘do what we want, at whatever time we choose’.

Russell argues that in doing so, ‘we have thrown away an essential part of our biology’. One recent example of this can be found in Samsung’s ‘Night Owl’ television advertisement, which features a woman jogging through a city in the middle of the night (2.00am), tracking her progress with a Galaxy Watch. The advert encourages viewers to pursue their health and wellness goals on their own schedules – despite the overwhelming objective scientific evidence that this can be extremely harmful.

It is this insight about our arrogant 24/7 society that underpins Russell’s new book, Life Time, published by Penguin on 19 May. Almost a handbook, Life Time presents the reader with a wealth of information on what scientists have discovered about sleep and biological circadian rhythms. The book is designed to help each of us ‘make an informed and evidence-based decisions about improving our sleep and circadian health to improve our lives.’ Life Time represents a generous sharing of a lifetime’s work, and demonstrates Russell’s commitment to the public understanding of science.

Russell Foster is perhaps best known for his team’s contribution to the discovery in the late 1990s of photosensitive retinal ganglion cells, a type of neuron in the eye. Unlike the eye’s rod and cone cells, they’re not responsible for forming images, but for detecting light, providing information to the brain about the length of day and length of night. The ground-breaking discovery of these cells and their function was a milestone in the now exploding field of circadian biology to which Russell has dedicated his working life.

Photosensitive retinal ganglion cells are important because they help to ensure that the human body’s circadian system, which is organised by a master ‘body clock’ in the brain, is kept in synchronisation with external light and dark. Without this mechanism, our rhythms would drift out of sync, leading to all sorts of problems. We are biological animals whose organs need to be ready during the active phase of the day to eat and process food, and during the resting phase to use stored energy to repair tissue, remove toxins, fight off infection, form memories, and generate new ideas.

Russell’s interest in circadian rhythms is intertwined with his interest in the purpose and mechanisms of sleep, which led him to set up the Sir Jules Thorn Sleep and Circadian Neuroscience Institute at the University of Oxford in 2012. Scientists here are uncovering more about the fundamental ancient processes that govern time in our lives. They are investigating what happens when sleep and circadian rhythms are disrupted, for example in shift workers, or in those of us who think we can somehow live outside days, pushing our waking hours into the night. Being out of sync can lead to increased stress hormones, heart disease, weight abnormalities, reduced immunity, increased risk of cancer, and emotional and cognitive problems. No wonder Russell was motivated to share some of the cutting-edge insights from the scientific community in order to help people make good decisions about how to live healthy lives.

So what are the practical take-home messages of this book? Perhaps the most surprising one is that there is no ‘one size fits all’ in terms of sleep. It’s not helpful to think that everyone should be aiming for eight hours sleep a night, for example, or even that the holy grail is to sleep right through the night without waking up. The sleep that you need is linked to your genetics and environment and can change over the course of your life. The book includes pointers for how to determine your own ‘chronotype’ – do you function best in the morning, the evening, or in between? Armed with this information you can adapt your behaviour to synchronise your internal clock to external time in the best way for you.

There are specific messages about the best time for various health interventions: stroke medications such as aspirin should be taken before you go to sleep rather than in the morning, because aspirin turns-off the “stickiness” of platelets which are made at night; a flu vaccine is better given in the morning because the immune system is upregulated during the daytime. Russell explains the scientific evidence for behaviours that will improve our sleep, such as not drinking caffeinated drinks after lunchtime, and not eating a large meal or discussing potentially difficult issues immediately before bedtime.

The advice in this book is not delivered in a didactic fashion by an aloof expert from the hallowed halls of academia, but by an engaging and entertaining human being who is clearly excited by knowledge and passionate about sharing it. Academics are used to writing, spending long hours documenting the methodology and results of their experiments, and writing applications to persuade funding bodies to provide grants to allow that research to continue. But only a few are motivated or skilled enough to write about the insights of their work for the benefit of ordinary people who want to live their lives to the full.

Russell has clearly enjoyed digging deep into the topic that has fascinated him for his whole life, and then distilling the findings and making them accessible and relevant. His vast experience of giving public talks has enabled him to get inside the minds of his audience, and he has used genuine questions from people attending such events to form the basis of the wide-ranging and sometimes quirky Q&A sections at the end of each chapter. This book demonstrates the most practical purpose of the scientific endeavour – to apply the lessons learned in order to improve our everyday lives.

To return to Philip Larkin and what days are for, let us leave the answer to Russell, whose hope for his book is that it can help us to ‘be healthier, more creative, make better decisions, gain more from the company of others, and view the world and all that it has to offer with a greater sense of curiosity and wonder’.

Patient recruitment is on-track in the Oxford-led DeTACT trial of safe, effective drug combinations to prevent the spread of artemisinin and multi-drug resistant malaria in Africa.

The global fight against malaria is at a critical point. Overall progress has now stalled and even worsened in some countries in Africa, where most of the world’s 627,000 deaths from malaria occurred in 2020.

The situation is becoming grave with recent studies confirming the growing prevalence in Rwanda and Uganda of P. falciparum malaria parasites partially resistant to artemisinins, which are the most important frontline anti-malaria drugs.

No new antimalarial drugs are expected in the near future. If multi-drug resistant falciparum malaria becomes established in East Africa and spreads to other parts of Africa, it is soon likely to compromise the efficacy of artemisinin-based combination therapies or ACTs — putting millions of Africans at risk of drug-resistant malaria infection and death.

The WHO has said this 'independent emergence of artemisinin partial resistance in the African Region is of great global concern.'

One possible solution — new drug combinations with artemisinins and two other frequently used antimalarial drugs (Triple ACTs or TACTs) — was found in 2020 by the large multi-centre, multi-country TRAC2 study to be highly efficacious even in places where ACTs were failing.

Before TACTs could be widely deployed to control artemisinin-resistance in Africa, however, their efficacy, safety and tolerability would first need to be confirmed in African populations, especially children.

A child suspected to have malaria being screened for recruitment into the DeTACT Trial at the Centre National de Formation et de Recherche en Santé Rurale (CNFRSR), Maférinyah, Guinea. © MORU. Photographer: Mehul Dhorda.

A child suspected to have malaria being screened for recruitment into the DeTACT Trial at the Centre National de Formation et de Recherche en Santé Rurale (CNFRSR), Maférinyah, Guinea. © MORU. Photographer: Mehul Dhorda.Led by University of Oxford-affiliated researchers based in Bangkok at the Mahidol-Oxford Tropical Medicine Research Unit (MORU), the Developing Triple Artemisinin-based Combination Therapies (DeTACT) trial is currently studying in eight African and three Asian countries two new TACTs to generate evidence that they are effective first-line malaria treatments and support their deployment in Africa to prevent or delay the emergence of artemisinin and multi-drug resistant malaria in Africa.

Funded by UKaid administered through the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO), DeTACT’s goals are ambitious.

'The emergence of artemisinin resistance in Africa is a serious concern, and its containment is paramount to avoid treatment failures in falciparum malaria in the future. TACTs can be an important contribution to this, both by delaying antimalarial drug resistance to the existing drugs, and by providing an effective treatment for multidrug resistant infections. DeTACT will provide the necessary evidence on TACTs, deliver a product that can be deployed, and will engage with national and global policy makers and other stakeholders to discuss the potential position of TACTs in the mix of antimalarial drugs,' says Professor Arjen Dondorp, the Principal Investigator of the DeTACT.

Besides comparing two existing ACTs (artemether-lumefantrine and artesunate-mefloquine) against two TACTs constituted of one additional drug added to each of these combinations (amodiaquine and piperaquine, respectively), DeTACT is conducting studies to forecast the impact of TACTs on controlling the spread or emergence of multidrug-resistant falciparum malaria leading to its elimination, and to examine the market readiness and ethical considerations of using TACTs across the malaria endemic world.

'The DeTACT Project includes modelling studies that will project the impact and cost-effectiveness of TACTs in preventing the spread of artemisinin resistance, explained Dr Chanaki Amaratunga, DeTACT Project Coordinator.'

'We are also conducting studies with all malaria stakeholders, starting from patients to researchers and policy makers, to elucidate the ethical and market aspects of their deployment. Along with the clinical trial, these studies constitute a comprehensive assessment of the expected advantages and potential barriers to the large scale use of TACTs,' said Dr Amaratunga.

Despite disruptions caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, DeTACT has already recruited over 700 patients, and aims to complete the recruitment of close to 4000 patients by early 2023.

The modelling, ethics and market positioning studies are well advanced and are expected to be completed by the end of 2022.

In addition, MORU has signed a memorandum of understanding with Fosun Pharma and Medicines for Malaria Venture (MMV) to collaborate with them to develop and pre-qualify fixed-dose combinations of TACTs prior to marketing them across Africa and the malaria endemic world.

'The DeTACT Trial will generate data not only on the efficacy and safety of TACTs but also on the pharmacokinetics of each of the drug components, including in malnourished children – a particularly vulnerable sub-population. In addition, there will be cutting-edge analyses, combining clinical trial data with that from whole genome and transcriptome studies, to improve our understanding of artemisinin and other antimalarial drug resistance,' said DeTACT-Africa Coordinator Dr Mehul Dhorda.

'We sincerely thank our partners conducting the field trials for maintaining their commitment to completing the trial in a difficult context,' Dr Dhorda added.

DeTACT is the third of three FCDO-supported multi-country, multi-site trials (TRAC and TRAC2) that have characterised artemisinin resistance and tested multi-drug resistant malaria treatments in South-East Asia. The work related to pharmacokinetics of antimalarials in malnourished children is supported by a grant from the Wellcome Trust.

One trial. Over 47,000 participants. Nearly 200 hospital sites, across six countries. Ten results. Four effective COVID-19 treatments. And behind them all, an army of countless researchers, doctors, nurses, statisticians and supporting staff.

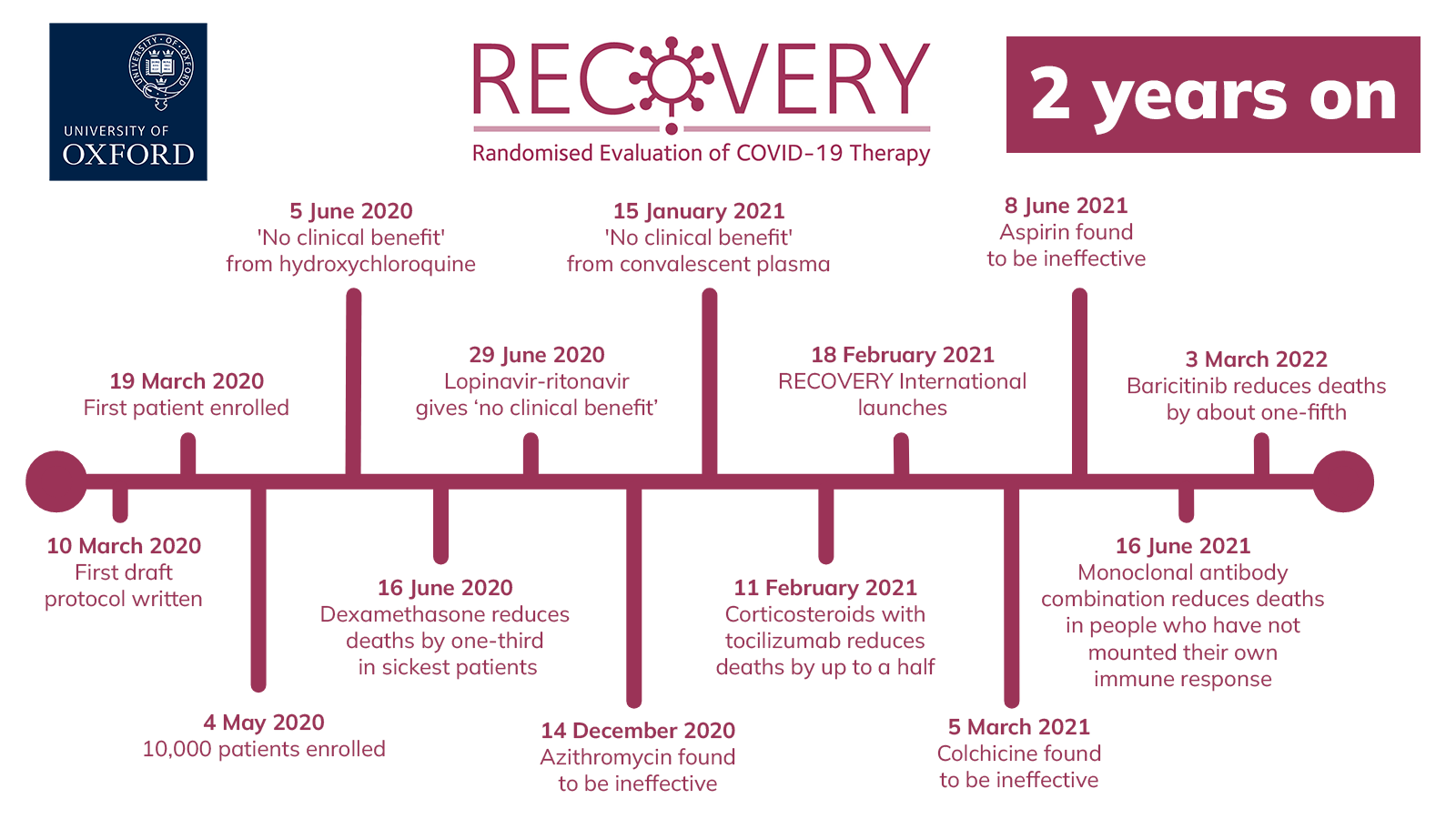

On the second anniversary of its official launch, the Randomised Evaluation of COVID-19 Therapy (RECOVERY) remains an exceptional study that is leading the global fight against COVID-19. The study is continuing to adapt to the changing dynamics of the pandemic, adding new promising candidate treatments, and launching in new countries with different population and healthcare systems.

It is likely that the true impact of RECOVERY can never be fully measured. But through discovering four treatments that effectively reduce deaths from COVID-19, it is certain that the study has saved thousands – if not millions – of lives worldwide. Crucially, low- and middle-income countries have shared these benefits, particularly since dexamethasone (the first treatment to be discovered) is inexpensive, easily administered and readily available in most hospitals.

The numbers are impressive, but each RECOVERY Trial participant has their own unique story, with many showing immense courage and altruism during one of the most difficult and frightening times of their life. As RECOVERY Trial participant John Hanna, who was put in an induced coma due to severe COVID-19, said: ‘Without the RECOVERY Trial, I don’t think I’d be here today, so I’m very grateful for all the work the team has done since the pandemic struck. I had minimum knowledge of clinical trials before COVID-19, but now I understand the important role these play, and that future studies will be needed to prepare the world for the next pandemic. Since taking part in the trial, I have become a member of the RECOVERY Trial’s Public Advisory Panel, and this gives me a feeling of involvement, belonging and pride to be contributing to something that has been so successful and continues to be.’

But the RECOVERY Trial’s impacts go far beyond saving lives and improving treatment of COVID-19 patients. Through pioneering a simplified, streamlined approach to running clinical trials, RECOVERY has redefined the speed at which life-saving results can be delivered. As Sir Martin Landray, Professor of Medicine and Epidemiology at Oxford Population Health, and Joint Chief Investigator for RECOVERY, said: ‘In 2019, I had no idea that I would be setting up a trial of treatments for an infectious disease, let alone a pandemic virus. I certainly would not have thought it possible to go from a blank piece of paper to enrolling the first patient in nine days, to finding the first life-saving treatment within ten weeks, and for it to be made standard NHS policy within three hours.’

Through integrating into routine care within NHS hospitals, RECOVERY has also shown the power of engaging front-line clinicians in research. Sir Martin Landray added: ‘For many doctors and nurses, their involvement with RECOVERY was their first experience of clinical research, and many have expressed an enthusiasm to continue. This experience could herald a new age for research, not just for this pandemic and the next but for other common infections such as influenza and chronic diseases.’

Timeline showing the development of the RECOVERY trial, from March 2020 to March 2022, including key drug discoveries

Dr Marion Mafham, Data Linkage Team Lead for RECOVERY, said: ‘RECOVERY brought clinical trials into everyday healthcare delivery, with frontline doctors and nurses consenting and enrolling participants directly at 177 hospitals across the UK. By integrating data from multiple sources, RECOVERY has produced rapid, reliable results improving outcomes in patients admitted to hospital with COVID-19. This required our team to use innovation and effective collaboration, identifying the right datasets, linking them to the trial participants and processing the data, while ensuring data security and quality - all whilst working remotely.’

Health and Social Care Secretary Sajid Javid said: 'Throughout the pandemic, the government has supported the UK’s world-leading research sector, with millions of pounds of funding for clinical trials into the most promising and innovative medicines. This includes around £2.1 million for the RECOVERY trial which has saved countless lives across the world.

'I am extremely grateful to the team at the University of Oxford – the brilliant work on RECOVERY has cemented the UK’s position as a global leader in identifying safe and effective treatments for Covid, helping the UK to live with this virus.

'I look forward to continuing to collaborate to identify more lifesaving treatments.'

For the wider public, the extensive media coverage of the study’s impacts has helped to increase awareness of the importance of clinical trial research, and the need for volunteers to take part in these. Meanwhile, beyond the UK it is hoped that the hospital sites participating in RECOVERY International will benefit from a long-term increased capacity for leading randomised controlled studies.

The RECOVERY Trial team extend their thanks to the many clinical staff who have made this trial possible, the thousands of patients who have taken part, and the funders for the study, particularly the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR), Wellcome, and UK Research and Innovation (UKRI).

By Professor Robert Hope, professor of water policy, director of the REACH programme.

Water is vital – not just for drinking and health, but for life chances and education. Without water, how can you learn? And yet more than half a billion children around the world do not have access to basic water supplies in schools.

Today, on World Water Day, the REACH programme to improve water security for 10 million poor people in Africa and Asia is releasing an animated film to highlight the critical importance of water, climate and education in Kenya.

We all recognise the need for water for handwashing as well as for drinking, sanitation, food preparation and cleaning facilities. But water matters to educational outcomes. In many countries, providing reliable and safe water to schools is a challenge. Globally, an estimated 584 million children lack basic water in schools. In Africa, four in ten rural schools do not have access to basic water supplies.

We all recognise the need for water for handwashing as well as for drinking, sanitation, food preparation and cleaning facilities. But water matters to educational outcomes

Girls are particularly affected by insufficient water, especially if there are no facilities and water for menstrual hygiene.

Global evidence shows girls who complete secondary education are more likely to get better paid jobs, shape their family choices, and pass on these opportunities to their children compared to girls who drop out of school early. In Kenya, investments are being made to ensure water is available in rural schools by providing tanks for rainwater harvesting. This is a good option in areas where rainfall is reliable throughout the year.

Rainwater harvesting tank. Photo by Rob Hope.

Rainwater harvesting tank. Photo by Rob Hope.But, in Kenya, rainfall patterns are increasingly unpredictable with many dry months. Rainwater tanks often do not last through dry periods, leaving schools with limited alternatives. Schools then face difficult choices depending on access to other water sources.

Oxford University researchers have supported the work of a local professional service provider, FundiFix Ltd, to guarantee repairs in water supplies in schools, clinics and communities water are fixed fast. Some 80,000 people benefit today from FundiFix’s work with future initiatives working to scale and sustain the benefits for millions more.

FundiFix bike. Photo by Jeff Waweru

FundiFix bike. Photo by Jeff WaweruVladimir Putin has long insisted Ukraine is part of the country he rules. This was painted more starkly than ever as he announced that Russian troops were undertaking a “special military operation” in its western neighbour. But to the rest of the world, what Russia is undertaking is simply an invasion.

Putin has been softening up the world for its latest foreign policy adventure for some years now.

'Kiev is the mother of Russian cities,' he wrote in March 2014. 'Ancient Rus is our common source and we cannot live without each other.'

A few days later, Russia completed the annexation of Crimea. Eight years later, during which time more than 14,000 people have died in a Russian-instigated war of insurgency in the Donbas region of eastern Ukraine, he has returned to this theme – backed by the might of Russia’s armed forces.

The Russian president made this intention crystal clear in an hour-long and fairly wide-ranging speech on February 21.

'Ukraine is not just a neighbouring country for us,' he told the Russian people in a national broadcast. 'It is an inalienable part of our own history, culture and spiritual space.'

He [Putin] repeatedly denied Ukraine’s right to independent existence – and, at times, that the country exists at all as an independent entity. Instead he appeared to accept the unity of the two countries as historical fact

He repeatedly denied Ukraine’s right to independent existence – and, at times, that the country exists at all as an independent entity. Instead he appeared to accept the unity of the two countries as historical fact. In doing so, he revealed the structures of an imperial ideology with a chronology and ambition that goes far beyond post-Soviet nostalgia to the mediaeval era. But to what extent is that ideology shared by Russians?

One of the striking elements of Putin’s latest speech about Ukraine, which accompanied the recognition of Donetsk and Luhansk as independent states, was his insistence that Ukraine exists as a by-product of Russian history, 'Since time immemorial, the people living in the south-west of what has historically been Russian land have called themselves Russians and Orthodox Christians.'

One of the striking elements of Putin’s latest speech about Ukraine...was his insistence that Ukraine exists as a by-product of Russian history...But he later undercut his insistence...stating, 'Modern Ukraine was entirely created by ...Bolshevik, Communist Russia

But he later undercut his insistence of these shared origins, stating, 'Modern Ukraine was entirely created by Russia or, to be more precise, by Bolshevik, Communist Russia.'

To him, the making of modern Ukraine only started 'after the 1917 revolution', and Ukrainians have 'Lenin and his associates' to thank for their state. This was a reference to Lenin’s creation of a federation of Soviet states, the USSR, out of the ethnic diversity of the former Russian empire.

In reality, Ukrainian aspirations for statehood predated revolution by at least two centuries. From the Ukrainian Hetmanate’s 1710 Bendery Constitution to the 1917 establishment of the West and Ukrainian People’s Republics and appeals at the Paris Peace Conference for status, Ukrainians have continuously asserted themselves as a distinct people.

The formation of the USSR was, in part, conditioned by the previous creation of these two independent Ukrainian Republics in the aftermath of the revolution and the disintegration of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. These republics stemmed directly from the 19th century Ukrainian romantic national movement that reassessed the impact of the Cossack past, fuelling the development of an identity centring on a distinct language, culture, and history.

In reality, Ukrainian aspirations for statehood predated [the Russian] revolution by at least two centuries

When the Bolsheviks, Lenin at their head, took control over the Ukrainian territories, the idea of Ukraine as an independent nation could not be ignored, and led to the independent status – on paper – of the Ukrainian Soviet Republic in 1922.

What Putin’s address reveals is the desire to plot Russian and Ukrainian history through the lens of imperialism

What Putin’s address reveals is the desire to plot Russian and Ukrainian history through the lens of imperialism. He is attempting to establish a direct line from shared ancient origins to a first and second Russian empire: one under the Romanov Tsars (1721-1917) and the second as part of the USSR.

Across those two imperial epochs, Ukraine is reduced to a tributary state and mentions of national aspirations are smothered. This is precisely the message that the Kremlin continues to disseminate in the 21st century.

A lack of popular appetite

But what does the Russian public believe? Three decades ago, when the USSR collapsed, only rare and often ultra-nationalist politicians resorted to imperial history in imagining Russia’s post-soviet future. As early as the 1990s, ultra-nationalist politician Vladimir Zhirinovsky advocated ceasing coal supplies to Ukraine as a tactic to bring back Russia’s lost territories, but he remained a fringe figure in Russian politics.

Still, in 2011 and 2012 Global Attitudes surveys conducted by Pew Research Centre, support for imperial ideology was not insignificant. When asked whether 'it’s natural for Russia to have an empire', only 31% of Russian respondents disagreed. Whether nostalgia for empire translates to appetite for war to 'regain territory' remains unclear.

It is impossible to paint all Russian perceptions of Ukrainians with the same brush. Russian feelings toward their neighbour have historically ranged from genuine feelings of brotherhood and warmth to virulent expressions of xenophobia manifesting in episodes of ethnic cleansing, such as the 1932 orchestrated famine known as the Holodomor.

Only 26% of Russians wanted the Donbas to become part of Russia, while 54% are in favour of varying forms of independence...War remains an unpopular choice, with only 18% of Russians unreservedly supporting armed conflict

But when it comes to the question of how Russia should position itself with regards to claiming eastern Ukrainian provinces as long-lost parts of the 'Russian empire', opinion is more clearly divided. Only 26% of Russians wanted the Donbas to become part of Russia, while 54% are in favour of varying forms of independence (within Ukraine or separate). War remains an unpopular choice, with only 18% of Russians unreservedly supporting armed conflict in defence of the two breakaway republics in a poll from April 2021.

Post-Soviet neo-imperialism

The rhetorical and physical erasure of Ukrainian history and identity makes it much easier to assert claims of shared Russian heritage

Ultimately, the use of 'empire' as an ideology reveals Russia’s yearning for – or sense of entitlement to – a third imperial regime. The rhetorical and physical erasure of Ukrainian history and identity makes it much easier to assert claims of shared Russian heritage. This will be important to bear in mind as we watch the development of this renewed conflict over Ukraine.

Parallels with other formerly colonised peoples abound. But, as Kenya’s envoy to the UN put it, no matter what conditions presided over the drawing of modern borders, 'we must complete our recovery from the embers of dead empires in a way that does not plunge us back into new forms of domination and oppression'.![]()

Olivia Durand is a Postdoctoral associate in history, University of Oxford

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

- ‹ previous

- 9 of 247

- next ›

From health policies to clinical practice, research on mental and brain health influences many areas of public life

From health policies to clinical practice, research on mental and brain health influences many areas of public life From research to action: How the Young Lives project is helping to protect girls from child marriage

From research to action: How the Young Lives project is helping to protect girls from child marriage  Can we truly align AI with human values? - Q&A with Brian Christian

Can we truly align AI with human values? - Q&A with Brian Christian  Entering the quantum era

Entering the quantum era Can AI be a force for inclusion?

Can AI be a force for inclusion? AI, automation in the home and its impact on women

AI, automation in the home and its impact on women Inside an Oxford tutorial at the Museum of Natural History

Inside an Oxford tutorial at the Museum of Natural History  Oxford spinout Brainomix is revolutionising stroke care through AI

Oxford spinout Brainomix is revolutionising stroke care through AI Oxford’s first Astrophoria Foundation Year students share their experiences

Oxford’s first Astrophoria Foundation Year students share their experiences DPhil student, Frankco Harris, reflects on his unique journey to Oxford and future plans

DPhil student, Frankco Harris, reflects on his unique journey to Oxford and future plans