Features

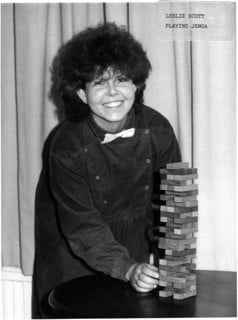

This month Senior Associate of Oxford’s Pembroke College, Leslie Scott, was honoured by her wildly popular invention Jenga being inducted in the US’s National Toy Hall of Fame. Sold in 117 countries across the world and loved by all ages, as a family- and pub-favourite, Jenga is now officially a classic.

Science Blog caught up with Leslie Scott, to find out how the game evolved and why its simple concept keeps people coming back for more.

How did Jenga come into being?

As a game, it evolved amongst my family when we were living in Ghana in the mid-70s. I moved to Oxford a few years later and had a set of these blocks and started to play it as a game. They weren't exactly like the Jenga blocks are now but the principle of the game was there.

I played a lot with friends here in Oxford. But it took a long time for the penny to drop that this didn't exist already as a game. People and children have obviously been piling up blocks of wood for years, but actually to turn that into a game, it just didn't exist.

So in 1982, I decided I was going to take this game to market. But that's when the issues started. I knew nothing about the toy industry and nothing about retail business. But I was just so convinced this was going to work.

What are the secrets to Jenga’s success?

Not many people realise this but each one of the blocks in the game are slightly randomly different from each other. And that's absolutely deliberate. Because without that, the game just really doesn't work. If they're all identical it just sits there. So that sort of randomness was a factor of the original, handmade wooden blocks.

I had to figure out how to mass market some of these flaws. Then there was the question of how many actual blocks there should be, plus their size. The original ones were slightly longer than Jenga blocks are now. That meant you couldn't assemble them three by three and make a stable tower to start with - there were gaps between each.

But I figured out that if you made them just slightly shorter you can square it up. So you can start with a fairly stable tower. The decision to go for 54 blocks was trial and error. You start with 18 rows and it just worked - I don't think there was anything more scientific.

How did you scale up production to maintain randomness?

I spoke to a carpenter I knew and asked him how would you do this. He came up with a very clever suggestion, which was to send the planks of wood through a sanding template that was not in itself 100% even. So these planks of wood would go through that template, and then be chopped up into the pieces.

The next stage was introduced by a group of people in Yorkshire at a place called Camphill. It's a sheltered community for adults with learning disabilities and other special needs - it's a movement all around the world. In Yorkshire they have a farm, they've got a dairy, but they also have a woodworking shop.

They had already been making wooden toys, and a person that I knew at Oxfam suggested talking to them. I went up and saw them and asked if they would be interested in doing this for me? And they said, “Yes”, provided that if it became successful, I took it elsewhere to be manufactured because they didn't want to spend the rest of their lives just churning out hundreds and thousands of the wooden blocks!

They came up with this idea of tumble polishing them. When you very lightly tumble polish it puts a nice sheen on them. It smooths the edges, but it doesn't smooth them totally - it introduces another level of slight inconsistency, so it's really clever.

I haven't seen how Hasbro make them now in vast quantities, but I understand it's not that different. This randomness is still built into it. People love playing with wood. There's that tactile element to it, but it's also actually key to the functioning of the game.

What do you think is Jenga’s enduring appeal?

I think it appeals because you can play it with anybody - as long as you've got a certain amount of dexterity. It still seems to require skills, but they're not skills that take a lifetime to learn. And plus, it is never the same. There's nothing inevitable about who's going to win. When you start the game you could make exactly the same moves, but it's not going to end up in the same way because of the randomness.

It's thrilling when you're teetering at 30 layers already. And it's terrifying it when it comes back to you.

Also, I didn't deliberately intend it to be a cooperative game. But if you watch people playing, once the tower gets beyond a certain height, most people end up wanting it to get higher. They really want it to get high, so it becomes almost like a team effort, in a funny way. The excitement comes in trying to get it as high as possible. Nobody deliberately wants it to fall over. So on one hand it could be considered a very competitive game, on the other hand, there’s actually quite surprisingly cooperative play involved. It's thrilling when you're teetering at 30 layers already. And it's terrifying when it comes back to you.

Where did the name Jenga come from?

I grew up speaking Swahili and the word jenga is the imperative form of kujenga, the Swahili verb “to build.” When I first put it on the market, I called it ‘Jenga the perpetual challenge’. And the company that took it on - first of all Irwin in Canada, and then subsequently Hasbro worldwide - hated the word ‘perpetual’. They said Jenga doesn't mean anything and nobody in North America will understand what perpetual means either! So I had a bit of a battle with them and I ended up saying, “Okay, okay, okay, you don't have to call it perpetual.” Even though I actually really meant it – I’d thought about that hard. It is always a challenge. It's not the ultimate challenge, but it's always a challenge. But I have this feeling that by giving up on 'perpetual' I got away with keeping Jenga [laughs].

Do you feel that your childhood influenced the development of Jenga?

I think we should leave children to think and do things for themselves a great deal more than we do now.

When we were kids, the idea that every moment of the day was somehow timetabled wasn’t there. Even at school, there were large, large chunks of time where we literally went out and played, and we were not being supervised for every moment. And, personally, I think we've got the concept of education a wee bit wrong. I mean, I think we should leave children to think and do things for themselves a great deal more than we do now.

If you think about some of the toys that are now produced for children, there's an awful lot that have stories already built into them. I think it's interesting that the National Toy Hall of Fame (which has inducted 74 items), have quite a large number that don't have an inventor as such. There's things like the cardboard box, the stick, marbles. What they're trying to recognise are playthings that have actually contributed to genuine play, playful play.

I think the opportunity to be creative, or the environments in which you can become creative arise when somebody else hasn't told you how to think about something. I don't know how Jenga fits into that, but play is a subject that really interests me.

What is a play – what is a game?

We use terms like “Somebody's got to play the game” or we imply that incredibly serious things are games - like business is a game and life is a game. I think we need to be quite careful how we define what we mean by ‘play’ and make sure that if we are saying, “it's all a game” that at least we actually know what those rules are when we're playing this game. And we know when we're outside of that too.

The thing about a game is that you've agreed to take part in it, it is something voluntary. Secondly, you've got a set of rules that you've agreed that you understand, you're playing by that set of rules, you're playing within a confined space, a delineated area, you're playing for a certain amount of time. So there's a beginning and there's an end to it too.

How do you feel about Jenga entering the National Toy Hall of Fame?

I am thrilled! And I’m honoured and delighted, too, that I am to be included in an upcoming Strong Museum exhibition of women who created a toy or game that became a classic. It’s very exciting.

The National Toy Hall of Fame at The Strong Musuem, was established in 1998 and recognizes toys that have inspired creative play and enjoyed popularity over a sustained period. Each year, the prestigious hall inducts new honorees and showcases both new and historic versions of classic toys beloved by generations. Final selections are made on the advice of historians, educators, and other individuals who exemplify learning, creativity, and discovery through their lives and careers. Toys are celebrated year-round in an exhibit at The Strong museum in Rochester, New York.

For more information about the hall, visit toyhalloffame.org.

It is a well-known fact that one of the things financial markets hate most is uncertainty. There are a lot of other things the market hates, but the ‘devil-they-know’, will almost always be preferable to the one they don’t know, even if the ‘fundamentals’ are not there.

This year, the markets have, by and large, underlined their love for certainty – surging on promises of government support from the US Fed and from Chancellor Rishi Sunak, propelling stock market prices higher, despite the ravages of the pandemic and the anticipated economic fall-out to come.

Whatever bad news emerged, as the virus swept the western world, there seemed no end to share price enthusiasm...towards the end of October, the reckoning finally seemed to have come

Whatever bad news emerged, as the virus swept the western world, there seemed no end to share price enthusiasm. Many observers were perplexed over how long this apparently counter-intuitive bull market could go on, considering the tax rises anticipated to follow. And, towards the end of October, the reckoning finally seemed to have come.

Share prices in London and New York tumbled to their lowest levels since March, when brokers took fright over COVID, before the regulators stepped in with reassurances. So, was this long-awaited end to market ‘madness’? In short, no.

According to the Associate Professor of Finance at Oxford’s Said Business School, Bige Kahraman, last month’s down-tick in share prices was a reflection of that market bête noir: uncertainty.

‘There was a lot of uncertainty prior to the US election,’ she said. ‘In the US, the market was uncertain about what was going to happen and that had an effect on prices.’

Traditionally, on entirely business grounds, the markets have preferred a Republican in the White House. It generally means low taxes and a benign business environment. But that old enemy ‘uncertainty’ trumps everything. And, since the election, the Dow Jones has risen consistently – even more since it became clear that President-elect Joe Biden is heading for Pennsylvania Avenue.

Traditionally, on entirely business grounds, the markets have preferred a Republican in the White House....But that old enemy ‘uncertainty’ trumps everything. And, since the election, the Dow Jones has risen consistently – even more since it became clear that President-elect Joe Biden is heading for Pennsylvania Avenue

Professor Kahraman said, ‘The markets are now back up to pre-COVID levels...the falls in October were just market uncertainty.’

But can this really go on for much longer? Will the reality of COVID economic havoc ever bite for the markets?

‘The indices do not represent the whole economy,’ explained Professor Kahraman. ‘Hard hit firms in the small and medium sectors are not represented in the markets...In fact, many of the really big firms which are represented have done very well recently.’

According to Professor Kahraman, big tech companies now account for some 30% of the equities markets and represent a safe haven for investors, who do not see any returns from interest-bearing accounts. Plus, many ‘tech’ firms have seen revenues going up during the pandemic, even if advertising revenue has gone down for the likes of Facebook and Google.

‘Amazon has worked really well,’ said Professor Kahraman. ‘Its business model is proving more successful than ever.’

The tech firms have emerged as the new ‘blue chip’ investments, ‘safer, whatever the fundamentals’, according to Professor Kahraman. ‘If investors want to put their money somewhere, these tech firms seem unlikely to go down that much.’

But, she said, ‘Prices are inflated right now. In a couple of years, there may be a return to real interest rates and that could have the effect of correcting the market.’

There is no sentimentality in the markets. Professor Kahraman said, ‘The falls were just election uncertainty. With a Democrat elected, the market is relieved, but not celebrating.’

Conventional wisdom has it that too many cooks spoil the broth. But such judiciousness is not usually considered the basis for scientific pronouncements or international rulings on the need to limit the number of people in kitchens. But, when it comes to video games, conventional wisdom, not science, forms the basis for our thinking and even pronouncements from global authorities, according to Professor Andy Przybylski, Director of Research at the Oxford Internet Institute.

The World Health Organisation, no less, weighed into the debate over gaming, pronouncing that ‘Gaming disorder’ is an addictive behaviour and has classified gaming addiction as a disease. Yet, according to Professor Przybylski, there has been no scientific study which takes account of industry data and sentiment – until now. The professor has just completed a formal scientific study into the impact on players of video gaming – Video game play is positively correlated with well-being. And it has some surprising results, which suggest the old wives were wrong, yet again.

The study suggests that experiences of competence and social connection with others through play may contribute to people’s well-being. Indeed, those who derived enjoyment from playing were more likely to report experiencing positive well-being.

The study suggests that experiences of competence and social connection with others through play may contribute to people’s well-being. Indeed, those who derived enjoyment from playing were more likely to report experiencing positive well-being

According to the research, ‘We found a small positive relation between game time and well-being for players of both games. We did not find evidence that this relation was moderated by need satisfactions and motivations. Overall, our findings suggest that regulating video games, on the basis of time, might not bring the benefits many might expect, though the correlational nature of the data limits that conclusion.’

So, stopping gamers from gaming is not necessarily a good thing. But the research is not a universal thumbs up, or perhaps down would be more correct, for a gaming analogy. Professor Przybylski emphasises the team looked at just two games and 3,000 adult players. But the study suggests there is a need to find out if the ‘moral panic’ over gaming is just that.

‘It’s fine to have an opinion about video games,’ says Professor Przybylski. ‘But, without research, you cannot know if this is a real thing or just your own ‘facts’. You can have your own opinion but you cannot have your own facts.’

It’s fine to have an opinion about video games...But, without research, you cannot know if this is a real thing or just your own ‘facts’. You can have your own opinion but you cannot have your own facts

Professor Andy Przybylski

Although games have been with us for the best part of four decades, the Oxford expert says this is the first study of its type, because it draws on data only available to the gaming industry. According to the report, ‘Policymakers urgently require reliable, robust, and credible evidence that illuminates the influences video game may have on global mental health. However, the most important source of data, the objective behaviours of players, are not used in scientific research.’

Contrary to conventional wisdom, using this method, Professor Przybylski’s study shows that the players involved in his study believed they benefitted to some extent from enhanced mental well-being as a result of lengthy games sessions on two specific games, Plants vs. Zombies: Battle for Neighborville and Animal Crossing: New Horizons.

Both are online ‘social’ games, where players engage with others at remote locations, and neither are in the 18+ ‘violent’ category.

Working with ‘blind’ data of gaming time provided by the games manufacturers, Electronic Arts and Nintendo of America, Professor Przybylski’s team surveyed the game players and ‘explored the association between objective game time and well-being, delivering a much-needed exploration of the relation between directly measured play behaviour and subjective mental health’.

The study does not mean, he says, that all video games are ‘good for you’ or that ‘all players benefit’. But, he maintains, his research should be a first step in carrying out a proper scientific study of the impact of gaming on players and their effects over time; he is keen to see more studies follow.

What worries Professor Przybylski is that, earlier this year, in an extraordinary volte face, the WHO’s US ambassador, suggested that young men be given video games, to ensure they stay indoors and comply with the lockdown, thereby limiting the spread of COVID. Wouldn’t this be another leap of logic, to add to the last one? If gaming really is an addition, as the WHO claimed, wouldn’t that be like giving an alcoholic a bottle?

‘This was a serious suggestion....But it’s an unlabelled bottle,’ says Professor Przybylski. ‘We don’t know what’s in it.’

Many local authorities can and should be doing more to help the young people they have looked after. Large numbers of care leavers (aged 18-25) report anxiety, loneliness, and lack of support, according to a long-term research project funded by the Hadley Trust and led by Oxford Professor of Education and Adoption, Julie Selwyn CBE, and Linda Briheim-Crookhall ( Coram Voice).

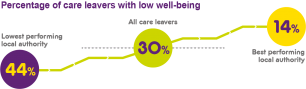

Among a host of appalling statistics, the most shocking finding in the recently published research on care leavers, is that the lives and futures of care leavers is genuinely determined by that over-used expression, a postcode lottery - see illustration 'percentage of care leavers with low well-being', below.

The lives and futures of care leavers is genuinely determined by that over-used expression, a postcode lottery

While care leavers in some areas report a positive experience and go to university alongside their peers, life for young people in other areas is horrifyingly different.

The report shows these Local Authorities are providing insufficient support with some young people feeling abandoned. Concerning, was the percentage (24%) of care leavers who recorded they had a disability or limiting long-term health problem: twice as many as their peers in the general population. This group of care leavers frequently reported feeling isolated and not having even one good friend. Many had high stress scores and 35% felt lonely always or often - see illustration immediately below for report findings.

A report on 11 Nov from the Children’s Commissioner, showing that young people in care are routinely being failed, accorded with the findings from the care leavers’ report.

Professor Selwyn says, ‘The variation in Local Authority can be stark. Nearly 80% of care leavers living in the best performing Local Authority area report that they feel safe but, in the lowest performing area, about half tell us they feel unsafe. They may be living in hostels, with adults who have problems of addiction and who are much older than them or living in a flat on their own.

‘But some young people feel that being in care has been a very positive experience. A quarter of care leavers in our surveys had very high well-being and many have gone to university. Some care leavers are here, at Oxford in our undergraduate, Masters and Doctoral programmes.’

In the lowest performing area, about half feel unsafe. They may be living in hostels, they may be living in hostels with adults who have problems of addiction and who are much older than them or living in a flat on their own....but some young people feel that being in care has been a very positive experience. A quarter had very high well-being

The report states, ‘There was an association between very high well-being and care leavers feeling that they had been treated the same or better than other young people. This suggests that services that actively seek to compensate for the additional challenges that their care leavers face are likely to help make their lives better.’

All this goes to show that young people leaving care can have good outcomes, but Professor Selwyn maintains the Local Authorities’ procedures are critical in making the difference.

Care leavers benefit from the Local Authorities’ policies in terms of housing and financial advice and support. Leaving care workers play an important and unsung role in helping young people transition to independent life. Care leavers also need to understand their histories but, surprisingly, 23% still did not have a full understanding of why they had been in care.

According to the report, ‘When the state steps in to look after a child, it is down to the state as their corporate parent, to step up to support care leavers to reach their full potential. Local authorities should want their children to do (at least) as well as other young people. When we compare how care leavers feel they are doing to other young adults, the difference is stark.’

Young people leaving care can have good outcomes, but Local Authorities’ procedures are critical in making the difference

Professor Julie Selwyn

The report shows that care leavers are much more likely to be struggling financially, with housing, or just with having someone they can trust compared with other young people. Care leavers with low well-being often felt afraid, they were more likely not to have a person in their life who listened, praised or believed they would be a success compared with other care leavers.

But the report insists, ‘Corporate parents should not accept that their care leavers do worse than other young people.’

And it recommends, ‘Address the continued postcode lottery by each local authority systematically measuring care leavers’ subjective well-being and identifying where their care leavers struggle and where they do better. Share the practices that promote positive experiences.’

Dr Selwyn’s report is based on 1,800 surveys of care leavers. Every Local Authority which takes part does so voluntarily and 50 out of 152 nationally have participated since 2017.

By David Macdonald, Director of WildCRU

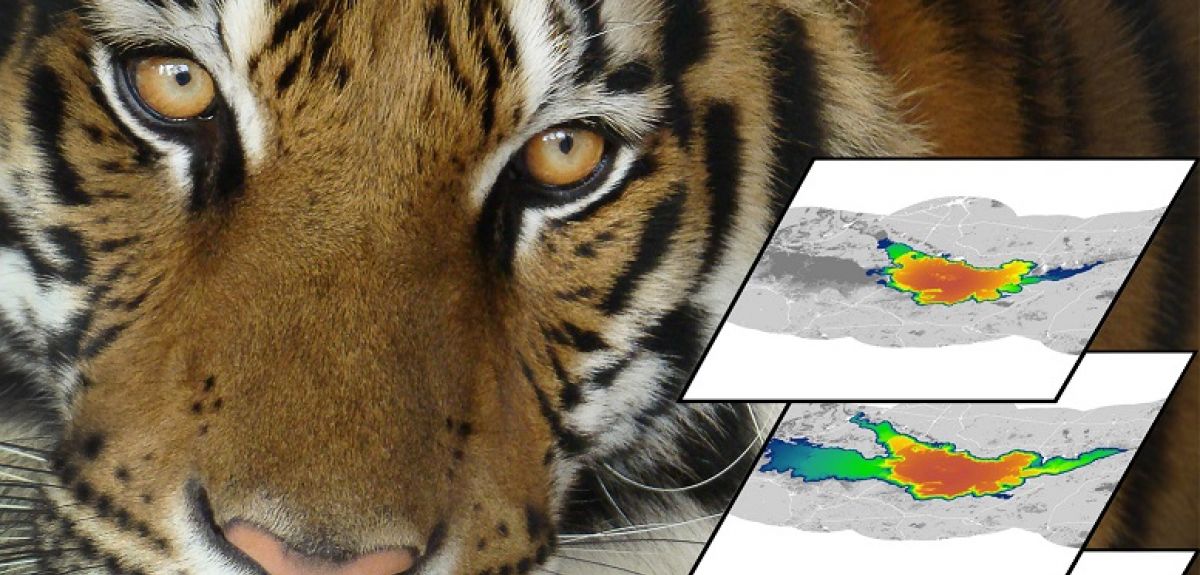

Tigers are in dire straits, with prospects for the Indochinese subspecies among the most dire of all. This is why I want to spotlight the work of Eric Ash for leading research on one of the few known breeding sites for the subspecies anywhere in the world.

Eric Ash, a doctoral student at Wildlife Conservation Research Unit (WildCRU), part of the University of Oxford’s Department of Zoology, has dedicated himself to the conservation of tigers in Thailand for the last nine years. Now, with our collaborators at the Freeland Foundation, he has led our new paper published in the journal, Land.

The under-studied and endangered Indochinese tiger faces extinction and continuing declines, a distinction that unhappily makes the subspecies a candidate for Critically Endangered status

The under-studied and endangered Indochinese tiger (Panthera tigris corbetti) faces extinction and continuing declines, a distinction that unhappily makes the subspecies a candidate for Critically Endangered status. Thailand plays a crucial role in its conservation – there are few known breeding populations in other range countries. Our work has focused on Thailand’s Dong Phayayen-Khao Yai forest complex (DPKY), a group of five protected areas and UNESCO World Heritage Site, where Eric and Freeland Foundation, in partnership with the Thai-government and Panthera, conducted a massive camera-trapping study to find out just how the tigers there were faring.

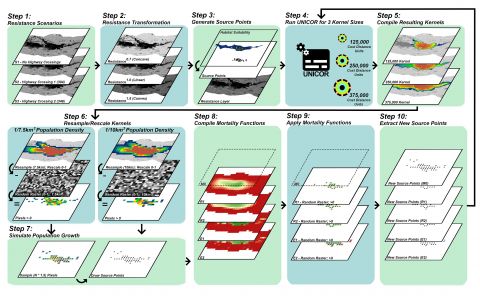

Importantly, we evaluate the sensitivity of population connectivity models to the variation and interaction of key factors, such as landscape resistance to movement, dispersal ability, population density, and mortality, over a series of timesteps. The article, led by researchers at WildCRU, offers insight into potential tiger range expansion scenarios.

The authors utilize spatially and temporally-dynamic simulations to model tiger population changes and dispersal from this landscape to potential habitat elsewhere in Thailand, Cambodia, and Laos, areas where tigers are thought to be extinct.Our new paper builds upon the remarkable news that this vital population of tigers could be recovering, as evidenced by signs that tigers are beginning to disperse from core areas into frontier habitat from which they had previously been extirpated

Our new paper builds upon the remarkable news that this vital population of tigers could be recovering, as evidenced by signs that tigers are beginning to disperse from core areas into frontier habitat from which they had previously been extirpated.

This was a huge analytical effort, informed by an even greater effort under arduous conditions in the field which generated over a million camera-trapping images and almost 80,000 collective trap nights over nine years. The team ran advanced analyses, requiring months of high-level computing, which produced 24,300 simulations of population, landscape connectivity, and density of dispersing individuals across the landscape to evaluate the effect of key factors.

The result? The computer models suggest that the tiger’s fate is extremely sensitive to variations in mortality and dispersal ability – and, over time, these two factors interact to strongly affect predictions. For the technical aficionado: incorporation of an explicit mortality component, reflecting differences in probability of survival across the landscape, combined with increased dispersal ability, resulted in considerably lower estimates of population and connectivity.

These results are hugely important for tigers, but they also offer an important lesson more broadly: given the importance of population connectivity modelling in cutting-edge ecological research, the approach of the WildCRU team can inform future assessments for rare or threatened species where empirical data are scarce – a challenge faced by many researchers around the world.

This study is among the first explicitly to evaluate the interaction of dispersal ability and mortality on population size, distribution and connectivity in a spatially and temporally explicit dynamic framework. The authors are convinced that future studies should adopt this approach, explicitly accounting for mortality risk across landscapes and potential interactions with dispersal ability over time. The ways in which these factors can vary over time in reality can drastically affect the simulated results. Importantly, for translating this research into impact, the study identified potential population growth and range expansion scenarios for tigers along with key factors relevant to their long-term management across this key landscape in Southeast Asia.

'How Important Are Resistance, Dispersal Ability, Population Density and Mortality in Temporally Dynamic Simulations of Population Connectivity? A Case Study of Tigers in Southeast Asia', Ash, E.; Cushman, S.A.; Macdonald, D.W.; Redford, T.; Kaszta, Ż. Land 2020, 9, 415. https://www.mdpi.com/2073-445X/9/11/415

- ‹ previous

- 28 of 247

- next ›

From research to action: How the Young Lives project is helping to protect girls from child marriage

From research to action: How the Young Lives project is helping to protect girls from child marriage  Can we truly align AI with human values? - Q&A with Brian Christian

Can we truly align AI with human values? - Q&A with Brian Christian  Entering the quantum era

Entering the quantum era Can AI be a force for inclusion?

Can AI be a force for inclusion? AI, automation in the home and its impact on women

AI, automation in the home and its impact on women Inside an Oxford tutorial at the Museum of Natural History

Inside an Oxford tutorial at the Museum of Natural History  Oxford spinout Brainomix is revolutionising stroke care through AI

Oxford spinout Brainomix is revolutionising stroke care through AI Oxford’s first Astrophoria Foundation Year students share their experiences

Oxford’s first Astrophoria Foundation Year students share their experiences DPhil student, Frankco Harris, reflects on his unique journey to Oxford and future plans

DPhil student, Frankco Harris, reflects on his unique journey to Oxford and future plans Oxford undergraduates reflect on their first term

Oxford undergraduates reflect on their first term