Features

Scientists at the University of Oxford have discovered that classical nova explosions are accompanied by the ejection of jets of oppositely-directed hot gas and plasma, and that this persists for years following the nova eruption. Previously, such jets had only been encountered emanating from very different systems such as black holes or newly collapsing stars.

A classical nova is the name given to an explosive event in our Galaxy. It has been known for decades that when a nova erupts, its brightness can increase by several orders of magnitude and can transform an undetectable star into an object that can be seen by the naked eye. This huge increase in brightness happens when matter is ripped away from one star onto the hard surface of a companion star, a compact object known as a white dwarf. The matter accreted onto the white dwarf becomes extremely hot and dense, providing the right conditions to synthesize heavier elements, a process known as thermonuclear runaway.

It’s amazing that jets emerge from these remarkable objects, in spite of the turbulence of a nova detonation

The Global Jet Watch, led at the University of Oxford by Professor Katherine Blundell, comprising telescopes separated in longitude around the world to follow sub-day variability in the Galaxy made this discovery possible. The team published this finding in early 2021, reporting the initial discovery of jets in a classical nova that had erupted during the pandemic lockdown of 2020 and was subsequently followed intensively with time-lapse spectroscopy with the Global Jet Watch in the days, weeks and months that followed.

In a second paper published by the Royal Astronomical Society, the team has demonstrated that the exact same behaviour is exhibited by four out of four classical novae that the Global Jet Watch has been monitoring. This collection of four eruptions includes different types of classical novae (including one hybrid type) suggesting that jets are a likely outcome for the classical nova phenomenon in general.

In a second paper published by the Royal Astronomical Society, the team has demonstrated that the exact same behaviour is exhibited by four out of four classical novae that the Global Jet Watch has been monitoring. This collection of four eruptions includes different types of classical novae (including one hybrid type) suggesting that jets are a likely outcome for the classical nova phenomenon in general.

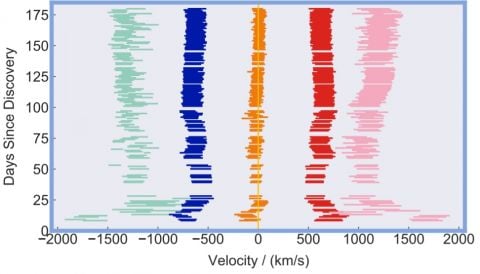

Graphic shows: Illustration of how the speeds along our line-of-sight to the nova that detonated in July 2020 changed in the days that followed its eruption. The changing speeds along our line-of-sight are believed to be because the directions along which the jets of hydrogen are squirted change with time, a phenomenon known as precession.

Besides now being able to study the phenomena of jets, their launch, their propagation and their precession in a new way, the discovery is also a significant advance in understanding the influence of classical novae themselves on our Galaxy, the Milky Way. The fact that they can propagate hot gas far, far away from the site of the explosion itself has implications for the enrichment of the inter-stellar medium within our Galaxy with the new elements synthesised in the course of the explosion. Further exploration and investigation of these implications is planned.

Dominic McLoughlin, the graduate student who had been investigating the time-series nova data, said; ‘The nova that erupted in July 2020 enabled us to crack the code. Discovering jets in the immediate aftermath of classical nova eruptions means we can now study them as they start launching and precessing – it’s not understood how jets actually get launched in general, despite the fact they happen all over space.’

Professor Katherine Blundell, who designed and instigated the Global Jet Watch, said: 'It’s amazing that jets emerge from these remarkable objects, in spite of the turbulence of a nova detonation – and it’s also amazing that the Global Jet Watch has persisted robustly throughout the turbulent times of lockdown. This opens up a whole new way to study the jet phenomena which is ubiquitous across the Universe.’

The nova that erupted in July 2020 enabled us to crack the code

The Global Jet Watch was designed to accomplish two important goals. One of these goals was to be able to provide time-lapse spectroscopy of evolving and dynamic systems in our Galaxy, an important class of which are the so-called micro-quasars which can be regarded as scaled-down, speeded-up models of quasars in the distant Universe. These new results demonstrate its effectiveness in following different types of optical transients as well as its resilience at a time when in-person visits to the observatories are not possible.

Professor Katherine Blundell said: ‘This discovery did not come about because of detailed plans and presumptions about the way the Universe is, but instead as a fun, auxiliary project adjunct to the main research programmes of the Global Jet Watch. Being open to exploring the Universe in new ways invariably seems to produce new insights into its richness and inner workings.’

The second goal of the Global Jet Watch was to engage young people in developing countries, especially girls, into science and technology through the doorway of astronomy which is a gateway and exemplar of so many areas of high-level science and engineering. In non-lockdown times, the schools around the world that host the observatories are free to use the telescopes before local bedtime.

The second goal of the Global Jet Watch was to engage young people in developing countries, especially girls, into science and technology through the doorway of astronomy which is a gateway and exemplar of so many areas of high-level science and engineering. In non-lockdown times, the schools around the world that host the observatories are free to use the telescopes before local bedtime.

The Global Jet Watch uniquely combines excellence in science with empowerment for school students, around the world; astronomy is a gateway to science for so many

The experience of controlling the telescopes, operating the cameras and exploring and capturing the night sky has proved to be a pivotal experience for many. Already some of the first students to have used the telescope at their school have gone on to study science and/or engineering at colleges and universities in their countries.

Brian Schmidt, the Vice-Chancellor of the Australian National University and Nobel Prize winner in 2011, said: ‘This discovery will change the way we think about classical novae. The Global Jet Watch uniquely combines excellence in science with empowerment for school students, around the world; astronomy is a gateway to science for so many.’

A group of students control the telescope

A group of students control the telescope

For a short video about the Global Jet Watch, please see: https://www.globaljetwatch.net/news/what-is-the-global-jet-watch/

To date, over 3.5 million people have died from Covid-19. Understanding its origins, with a view to preventing any future such pandemics, is therefore of global importance. Covid-19, known formally as SARS-CoV-2, is a coronavirus, and historically these have come to afflict humans through spill-over from wildlife sources. This was the case with the Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) outbreak in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, in 2012, spilling-over from dromedary camels, killing 858 people; similarly the SARS-CoV epidemic (for which there is still no cure) that began in Guangdong in 2002 and killed 744 people, spilled-over from palm civets as an intermediary, transferring infection from cave-dwelling horseshoe bats.

We had been gathering data collected from across Wuhan’s wet markets…which put our team in the right place at the right time to document the wild animals sold in these markets in the lead up to the pandemic

Not surprisingly then, the finger of blame has been pointed at wildlife trade in the wet markets of Wuhan, Hubei, China, where this Covid-19 outbreak seems to have originated. Candidate species include bats, which are definitive hosts brewing coronaviruses, and both pangolins and palm civets as potential intermediaries; although the most recent genetic data suggest that the variant found in these latter species isn’t quite similar enough to the human variant to be a totally convincing source. Nevertheless, through 14th Jan to 10th Feb this year the World Health Organization (WHO) sent an investigative team to Wuhan, where part of their remit was to try to ascertain, post hoc, what animals were being sold in markets prior to closures. Their report was inconclusive, but drew attention to the particular need to monitor bat and pangolin trading.

Our investigation found that both bats and pangolins had an alibi – neither was there!

Working with our colleagues based at China West Normal University, Nanchong, and Hubei University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Wuhan, Xiao Xiao and Zhao-Min Zhou on the ground in China, the WildCRU team had been gathering data collected from across Wuhan’s wet markets through May 2017 and November 2019. This research, begun before Covid-19 focused a spotlight on these markets, was actually motivated by a study of tick-borne (no human-to-human transmission) Severe Fever with Thrombocytopenia Syndrome, which put our team in the right place at the right time to document the wild animals sold in these markets in the lead up to the pandemic. Our investigation, published today in Nature-Scientific Reports, found that both bats and pangolins had an alibi – neither was there!

Caged marmots above a cage containing hedgehogs, Huanan seafood market prior to closure

Caged marmots above a cage containing hedgehogs, Huanan seafood market prior to closureWith these huge concentrations of diverse species under one roof, while we discovered no evidence supporting original spill-over from candidate bats or pangolins in Wuhan, it would seem but a matter of time before some other unwelcome disease might skip into the human population. Indeed it is estimated that around 70% of all diseases afflicting people originate in animals, think Avian Influenza, HIV, Ebola, etc.

Commendably, with this risk in mind, on the 26th of Jan 2020, China’s Ministries temporarily banned all wildlife trade as a precautionary step until the COVID-19 pandemic concludes. Subsequently, on 24th Feb 2020, they permanently banned eating and trading terrestrial wild (non-livestock) animals for food. These interventions, intended to protect human health, redress previous trading and enforcement inconsistencies, will have collateral benefits for global biodiversity conservation and animal welfare, and will hopefully prevent some future tragedies.

Professor David Macdonald is Director of WildCRU, part of the Department of Zoology, University of Oxford

Genetics and genomics are increasingly in the news. People can buy genetic tests on the internet, without providing a medical reason or involving a health professional. But how useful is personal genetic health information, and are there any downsides to buying tests?

I am a researcher in the Radcliffe Department of Medicine at the University of Oxford, and a genetic counsellor working with patients with inherited cardiac disease and their families. I see at first hand the benefits of genetic testing in the NHS, but also the variety of questions people want to discuss before going ahead with a test.

Buying a ‘direct to consumer’; (DTC) genetic test is different from an NHS genetic test in many ways, so when the UK Parliament announced an inquiry into Commercial genomics in 2019, I submitted written evidence along with many health professionals and academics, commercial providers and other interested parties.

The ‘Research & Public Policy Partnership’ scheme opened in late 2019 and seemed a good opportunity to start to build a programme of research that would have policy input from the start, ensuring its relevance for policy. The University Policy Engagement Team suggested approaching Dr Peter Border at the Parliamentary Office of Science and Technology (POST). Together with a General Practice and ethicist colleague, Dr Andrew Papanikitas, we put together a proposal outlining how we would work together and what we wanted to achieve.

We wanted to consider a range of perspectives about three sources of personal genetic health information: the NHS... commercial genetic testing... and research testing

We had planned an event bringing together a range of stakeholders in April 2020 in Oxford, but due to the COVID 19 pandemic it was quickly clear that could not happen. Pivoting quickly, one of our first spends was a subscription to an online meetings platform, and in fact the team has never met in person. We spent some time thinking about how we could adapt, and arrived at a plan to hold a series of online meetings with the people whose views we were interested in hearing.

We wanted to consider a range of perspectives about three sources of personal genetic health information: the NHS, which offers genetic testing to people with a rare disease or cancer and at risk relatives, commercial genetic testing which can be bought by anyone who has the financial means, and research testing.

We reached out to commercial providers, NHS professionals, genomic scientists, patient representatives, legal experts, charities funding medical research, and ethicists and other scholars with expert knowledge. Fortunately most people contacted agreed to take part; perhaps an advantage of the adapted setup meant that people could more easily commit to a shorter (90 minutes) meeting from home.

The meetings felt quite intense because we covered a lot of ground, but our mild worries that witnesses might clash were not realized – everyone was good-natured

All meetings were recorded and professionally transcribed. After each meeting the team analysed the transcript, met to discuss in depth and agree areas of further interest. This process allowed us to direct the next discussion, by posing key questions to one or two ‘witnesses’, and encouraging other witnesses to offer perspectives. The meetings felt quite intense because we covered a lot of ground, but our mild worries that witnesses might clash were not realized – everyone was good-natured.

Our learnings fed into a summary document for POST which contributed to the parliamentary inquiry.

We have successfully bid for more funding with an additional policy partner, Health Education England Genomics Education Programme to develop inclusion of ethical considerations, including those identified in our partnership, into health professional education.

Looking to the future, we will use what we’ve learned to articulate areas requiring further policy-directed research.

This has been a new way of working for Andrew, Peter and me. The practical issues raised by needing to work collaboratively yet remotely seemed very challenging at the start, but have perhaps been balanced by the advantages offered by setting up a structure for accessible meetings.

The three of us have very different professional backgrounds, and that has sometimes meant listening and adapting to unfamiliar ideas and ways of thinking. The content of the outputs we’ve generated is very different from those I had expected, and have highlighted new areas of interest for me. The new project is testament to the value we’ve derived from the partnership.

Dr Liz Ormondroyd is a BRC funded researcher based at the Radcliffe Department of Medicine. Her partnership with the Parliamentary Office of Science and Technology was funded by the University of Oxford Research & Public Policy Partnership Scheme.

By Dr Manuel Spitschan and Coline Weinzaepflen

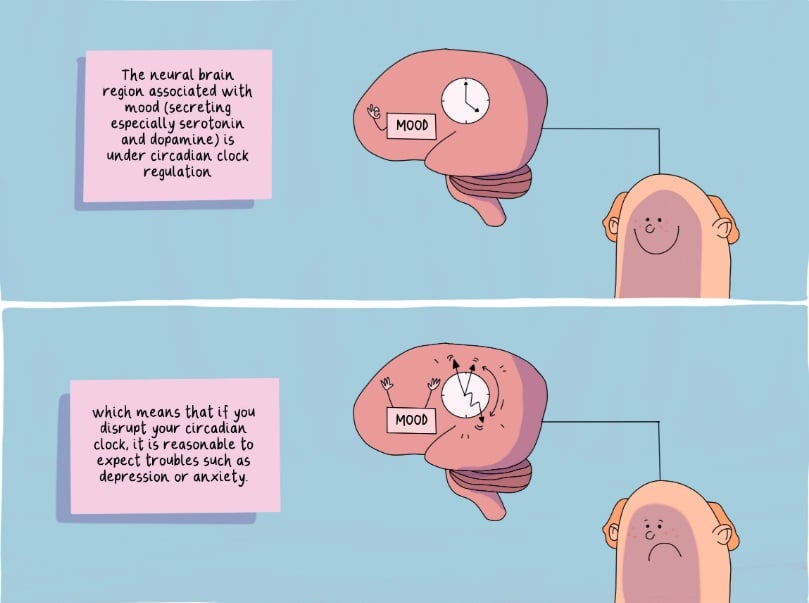

We are very excited to share our new comic book "Enlighten Your Clock: How your body tells time". The main protagonist is a cat – a pet species notable for seemingly sleepy behaviour – guiding the human character. As the biological clock underlies many aspects of our physiology and behaviour, the book addresses a key need to explain how the environment impacts on our brain and our body.

We designed this book for teens and above who are curious about circadian rhythms, sleep, and the effects of light on our body and brain.

The editor - Dr Manuel Spitschan

In my research, I investigate how light helps us see and controls our biological clock. We’ve known for a while looking at a bright light at the wrong time - specifically in the evening and at night - can upset our circadian clock.

Over the past few years, the importance of a good night’s sleep has moved into the focus of many people’s attention, and it is something that might feel difficult to attain while a global pandemic is happening around us.

When Coline started her internship with me as part of her Master’s project, and I learned that she was an illustrator, I proposed the idea of a comic book to her.

I’ve always been fascinated by how to best communicate complex scientific messages to a clear message that is accessible but doesn’t “dumb down” the content. I hope the book becomes a valuable resource for teenagers, parents, teachers, and everyone interested in this topic across the UK and beyond.

The writer and illustrator - Coline Weinzaepflen

I’ve always enjoyed making meaningful drawings in illustrations or comics. Making science accessible as much as possible to people can be a significant challenge for the scientific community.

That’s why I had a lot of enthusiasm working on this comic book. This project merged two things that I love: explaining biological concepts that I am fascinated by, and drawing (cat) cartoons.

The idea was to develop a format enjoyable for teenagers and adults, giving all the keys to understanding better sleep and what happens in their bodies and brains during the day and at night.

When I approached Manuel initially to do an internship in chronobiology, I had no idea that I would be able to combine these two interests of mine.

Making the comic book was exciting because we didn’t want something too complicated or too obvious. Part of the process involved the precious help of students from Cherwell School, who helped make the comic as accessible and engaging as possible.

I hope we’ve accomplished our mission: that this bit of science will enthral many people and hopefully give them the desire to know more!

Dr Manuel Spitschan, who wrote the comic book, is a University Research Lecturer, in the Department of Experimental Psychology, University of Oxford

Coline Weinzaepflen, who illustrated the comic book, is a neuroscience student and Illustrator

The comic book was developed within the Sleep, circadian rhythms and mental health in schools (SCRAMS) network, which Dr Spitschan is a member of, and was funded by an MRC/AHRC/ESRC Engagement Award in the Adolescence, Mental Health and the Developing Mind (MR/T046317/1: Sleep, circadian rhythms and mental health in schools (SCRAMS)).

The comic book (licensed under CC-BY-NC-ND license) is available for free as a PDF on https://enlightenyourclock.org/.

Cameron Hepburn is not an environmentalist from central casting. In person, Oxford’s professor of Environmental Economics comes across more like...well, an economist or a successful entrepreneur (he laughs), rather than a clichéd protestor, set on gluing himself to an inanimate object. But this is what makes him all the more convincing and persuasive. When he says, we need to take action now, the automatic response is: how not why.

The economist is under no illusion about the structural challenges and is sought out by governments around the world, looking to meet challenging Net Zero targets and ‘build back better’

As someone who has been at the cutting edge of environmental issues since the early 2000s, before the term ‘climate change’ was common currency, Professor Hepburn is insistent about the need to move away from a carbon-based economic model. But the economist is under no illusion about the structural challenges and is sought out by governments around the world, looking to meet challenging Net Zero targets and ‘build back better’.

The youthful professor is both reassuring and realistic, pointing out economic upheaval will take place over decades, as old industries are replaced by new jobs and, he maintains, technological change means the costs of conversion are coming down – a welcome thought for both countries and consumers.

Talking as the Government announces he is to lead a multi-million-pound project investigating greenhouse gas capture, Professor Hepburn is adamant the time is past for delay and that we now have to cut our carbon emissions, while actively removing greenhouse gases from the atmosphere.

It’s not an either-or-situation. We have to reduce emissions as fast as possible, and scale up our capacity to remove greenhouse gases from the atmosphere

Professor Cameron Hepburn

The ambitious project, announced today, encompasses leading environmental scientists at universities around the UK – and funds cutting-edge research into ways of removing the gases and storing them, permanently.

‘There’s a lot of very clever science underway in the UK and around the world,’ says Professor Hepburn. ‘Scientists have developed machines to capture carbon dioxide from the air and bury it underground. Others are restoring ecosystems to lock-up carbon in trees, plants, and soils. Still others are studying ways to accelerate the natural processes by which minerals in rocks absorb carbon dioxide from the air. ‘

‘It’s all incredibly interesting and potentially vital,’ he says.

It might seem a strange comment for someone who started their career working for Shell, the oil giant. But, says Professor Hepburn, his early encounter with fossil fuels convinced him that this was ‘even then a sunset industry’ and it began him on the road to his environmental work.

‘It’s important that we look at the societal impact as well as the political and structural impacts,' he says. ‘We have delayed for long enough, so that we have no choice but to explore ways to get greenhouse gases out of the atmosphere, which also help us achieve other social and environmental goals.’

Professor Hepburn heads the project’s Hub, which will coordinate the work, and look into ways of scaling up the research to economic viability, as well as making it possible in the political and legal framework. Oxford, and its partners at other universities, will provide the ‘central brain’, he says. His team will gather evidence, verify research and provide data.

The young Cameron lived with his parents and siblings in an idyllic environment in the Australian outback, with lots of camping expeditions and life in the outdoors. It sounds more Skippy than Crocodile Dundee

It was a path which began in the outback of Australia, where the young Cameron lived with his parents and siblings in an idyllic environment with lots of camping expeditions and life in the outdoors. It sounds more Skippy than Crocodile Dundee, with Mr Hepburn senior nicknamed ‘Leafy’ Leigh Hepburn because of his interest in nature.

Cameron won a scholarship to a school in Melbourne, where his fellow alumni include many leading Australians – including a host of army chiefs, bishops and...Barry Humphries (not a contemporary).

From there, he went to Melbourne University, where the young scholar was awarded degrees in Engineering and Law. But, after the brush with Shell and then some law firms, where he was engaged designing complex legal contracts for the financing of power plants, the graduate knew, ‘It was very clear that this was not how things should be done’.

Changing tack, he applied for a Rhodes scholarship to come to Oxford to take a masters in Economics. He intended to be in the UK for two years. Twenty one years later, now married with three children, he is still here, having taken a doctorate in Economics, become a researcher, then a senior researcher, now the Professor of Environmental Economics. Having changed track twice, he knew he did not want a conventional economics career.

‘Environmental economics was virtually invisible,’ he says. ‘I didn’t want to spend my time looking at the money supply...I was much more interested in thinking about the impact of climate change.’

Environmental economics was virtually invisible... I didn’t want to spend my time looking at the money supply...I was much more interested in thinking about the impact of climate change

Professor Hepburn

Laughing, he adds, ‘I thought it was worthy of a career – and so here I am.’

'Climate change was on the scientific agenda for decades before climate concerns became widespread and governments around the world were pledging to reduce emissions, and environmentalism became mainstream.'

He adds, 'It’s a shame Australia didn’t begin the transition [from a carbon-based economy] back in the 1990s. We could have done things more steadily. The later you leave it, the more difficult some things become, as they have to be done faster.’

But he says, ‘The good thing is, everyone has woken up. We have delayed long enough.’

There should be no need for mass redundancies, to meet the UN’s 2050 Net Zero target. Older industry jobs will be more than replaced by others – and it does not have to happen all at once

Professor Hepburn

However, Professor Hepburn does not underestimate the challenges and the costs of transitioning away from fossil fuels- and the need to reassure. He maintains there should be no need for mass redundancies, to meet the UN’s 2050 Net Zero target. Older industry jobs will be more than replaced by others – and it does not have to happen all at once.

While stressing there will be costs of going Net Zero for some countries, businesses and individuals, Professor Hepburn anticipates that new technologies will emerge and existing ones will become much cheaper. He says, ‘Smarter, cleaner tech is getting better and cheaper all the time...it won't be long before it would be crazy for anyone to buy a fossil fuel-driven car.’

He admits that domestic heating is a ‘big challenge’, with most UK homes reliant on fossil fuel energy. But he maintains, we will not be sitting at home shivering in 20 years. Technological progress is already happening which will assist in making the switch to clean heating cheaper. Overall, he thinks, the savings on cheaper electricity and transport will help offset the costs of investment on clean heating.

Smarter, cleaner tech is getting better and cheaper all the time...it won't be long before it would be crazy for anyone to buy a fossil fuel-driven car

Professor Hepburn

The same goes, he hopes, for air transport, with short-haul flights potentially driven by battery-powered electric motors, and longer haul adopting hydrogen and ammonia solutions.

According to Professor Hepburn, though, we do not need to wait for technology to start the process of improving sustainability. Nature based solutions can be deployed right now. ‘Leafy’ Leigh was right, it seems. Professor Hepburn says, ‘Trees are the oldest tech in the world....nature has been doing this [taking carbon out of the atmosphere] for millennia.’

He is optimistic about the future, despite the delays in getting started, and points to the fact that countries and businesses around the world have given Net Zero pledges, to slash emissions, which cover two thirds of international GDP. But will the fine words translate into action? Many critics focus on whether the ‘big polluters’ are going to take action and whether vested interests will take this lying down. Professor Hepburn stresses, ‘The credibility of such targets is vital.’

And he maintains key carbon emitters should accelerate towards Net Zero targets, as the technology becomes more affordable. But Professor Hepburn admits, ‘There will be winners and losers in the transition [think sunset industries]. It needs to be a just transition...but the transition will create many more jobs than it destroys. There will be net gains both to economies and workers.’

The reality of transition to sustainable power, like many new technologies in the past, will be far less difficult than is currently apparent

Professor Hepburn

As an economist, he points out, economies have transitioned all the time. When there has been seismic shifts in technology, they have adjusted naturally, ‘The economy can be quite flexible but we need transition schemes for reskilling.’

He adds, ‘It is critical that financial and economic ministries are looking at this – and they are.’

Reassuringly, says Professor Hepburn, the reality of transition to sustainable power, like many new technologies in the past, will be far less difficult than is currently apparent.

‘Clean electricity is already cheaper in a lot of parts of the world, solar and wind is cheaper and electric vehicles are simpler and easier to maintain.’

Who’d be a petrol-head? ‘Within a few decades, he wonders, I think we will look back at cars spewing out toxins into our lungs as even worse than horses defecating in the middle of our streets.’

And yet, and yet, what can the UK do, or other European countries, when we are not responsible for most of the world’s emissions? Professor Hepburn is typically enthusiastic: Britain has been leading on climate science for a decade

And yet, and yet, what can the UK do, or other European countries, since we are not responsible for most of the world’s emissions?

Professor Hepburn is typically enthusiastic, ‘Britain has been leading on climate science for a decade. The whole concept of Net Zero arguably came from Oxford, as did Net Zero investment finance and Net Zero economics.’

Pointing out the greenhouse gas project could deliver technology for the world, he insists, ‘These are ideas that matter, drivers of change. The UK is important for wider science and theories. It’s the first large country which had a formal architecture with the government's committee on climate change and the net zero legislation – it’s not just a theory for the UK.’

And, says Professor Hepburn, Oxford’s environment and structure has been key in propelling environmental research up the agenda.

‘It’s a pretty unique place,’ he says. ‘The college system means we meet people from other disciplines all the time [which facilitates and drives critical inter-disciplinary cooperation]. You can find yourself sitting next to a classicist or a specialist in Physics.’

Also, he says, the Oxford Martin School, the university’s multi-disciplinary research organisation, drives key research, involving experts from every discipline and has led to environmental collaboration on pressing international topics. And, he notes, that the Smith School, which he directs, has interdisciplinary research right at the heart of the mission.

While we stand on the cusp of massive change, Professor Hepburn says, he is hopeful, ‘2019 may have been the peak year for fossil fuels...the global community can no longer deny it makes sense to transition. Why sink more money into gas and coal, when the future is clean?’

See £30 million official backing for Oxford-led greenhouse gas removal programme | University of Oxford

- ‹ previous

- 19 of 247

- next ›

World Malaria Day 2024: an interview with Professor Philippe Guerin

World Malaria Day 2024: an interview with Professor Philippe Guerin From health policies to clinical practice, research on mental and brain health influences many areas of public life

From health policies to clinical practice, research on mental and brain health influences many areas of public life From research to action: How the Young Lives project is helping to protect girls from child marriage

From research to action: How the Young Lives project is helping to protect girls from child marriage  Can we truly align AI with human values? - Q&A with Brian Christian

Can we truly align AI with human values? - Q&A with Brian Christian  Entering the quantum era

Entering the quantum era Can AI be a force for inclusion?

Can AI be a force for inclusion? AI, automation in the home and its impact on women

AI, automation in the home and its impact on women Inside an Oxford tutorial at the Museum of Natural History

Inside an Oxford tutorial at the Museum of Natural History  Oxford spinout Brainomix is revolutionising stroke care through AI

Oxford spinout Brainomix is revolutionising stroke care through AI Oxford’s first Astrophoria Foundation Year students share their experiences

Oxford’s first Astrophoria Foundation Year students share their experiences