Features

The law on marriage and civil partnerships, for both opposite and same sex couples, has been made equal – but not completely symmetrical; that is, concerning the option of converting one form of legal union into another, according to research by John Haskey, Associate Fellow at Oxford’s Department of Social Policy and Intervention published in Family Law.

Both same sex and opposite sex couples can become civil partners or they can marry. Consequently there are four possible ‘conversions’ of one form of legal union into another, only one of which is currently permissible - same sex civil partnerships can be converted to same sex marriages. The other three ‘conversions’ are not legally possible at present: same sex and opposite sex couples cannot convert from a marriage to a civil partnership, and opposite sex couples cannot convert from a civil partnership to a marriage.

One benefit of allowing all four conversions would be that couples could periodically reassess the form of their legal union and convert it to the alternative kind if they judged it appropriate. Such a review and reassessment might well be beneficial to the health of the relationship

John Haskey

An argument against two of these unavailable conversions is that the couples concerned did have the choice between the two legal unions: for example, opposite sex couples who formed a civil partnership did have the opportunity of marrying; similarly same sex couples who had married, could have opted instead for a same sex civil partnership, as the latter were introduced before the former.

In contrast, however, opposite sex couples who married earlier did not have the opportunity to have a civil partnership and there is the possibility that such conversions might be legislated. Other considerations and arguments might be deployed in favour of legislating the remaining two conversions.

According to John Haskey, ‘One benefit of allowing all four conversions would be that couples could periodically reassess the form of their legal union and convert it to the alternative kind if they judged it appropriate. Such a review and reassessment might well be beneficial to the health of the relationship.

'Undoubtedly perceptions about the characteristics of civil partnerships and marriages differ, and these differences may well vary for different age groups, so that conversions may be thought to allow some flexibility - a potential benefit - in the form of legal union with its associated expectations.’

He adds, ‘Another benefit of allowable conversions is that if a partner or spouse has a gender change, they can still remain married or as a civil partner with no disruption to their civil partnership or marriage - the union just changes for example, from an opposite sex one to a same sex one.’

The article reveals, the vast majority of same sex couples have not opted to convert their civil partnerships to marriages. John Haskey writes that, after December 2005, when same sex civil partnerships were introduced, 13,000 couples formed civil partnerships in the following nine months of 2006. After the initial rush, the monthly numbers fell to less than 1,000 a month and a seasonal pattern quickly emerged. Up to the end of 2017, he estimates, some 63,000 same sex partnerships had been formed.

Same sex marriage was introduced in March 2014, and the option to convert a same sex civil partnership to a same sex marriage in December 2014. The article estimates that up to the end of 2017, 23% (14,000) of civil partners had opted for conversion to marriage.

An important element in the argument for having, and retaining, civil partnerships has been that they avoid what many see as the paternalistic aspects of marriage, the couple preferring, it is claimed, to be equal partners, rather than husband and wife with their traditional roles

John Haskey

According to John Haskey, ‘The fact that a large proportion of civil partners have not converted their partnership may well reflect their contentment with the new status. Alternatively, they may have been unaware of the facility to convert, or even (erroneously) considered themselves either married or ‘as if married’.’

He adds, ‘An important element in the argument for having, and retaining, civil partnerships has been that they avoid what many see as the paternalistic aspects of marriage, the couple preferring, it is claimed, to be equal partners, rather than husband and wife with their traditional roles. (Inevitably, though, one wonders whether, had same sex marriage been legislated early and first, there would have been any civil partnerships on the statute book at all.)’

John Haskey concludes, ‘Overall, there has been extraordinary progress over the last two decades, and much of the advance can be attributed to the adherence to the principles of equality and non-discrimination, which, no doubt, will also play an important part in future reform. Three new legally recognised relationships in the space of less than two decades contrasts with centuries of having only marriage is remarkable, and may signify a new spirit of progressivism.’

The full article can be read here: Perspectives on civil partnerships and marriages in England and Wales: aspects, attitudes and assessments (familylaw.co.uk)

International concern over issues around representation has thrown a light on the classical music world and inspired ‘Diversity and the British String Quartet’, a wide-ranging collaborative project as part of Oxford’s TORCH Humanities Cultural Programme. Although focusing on the string quartet, it explores larger debates around inclusivity, access and identity within the classical music scene.

While the string quartet has associations of high art and intellectualism, it has been a medium for diverse and different British composers

While the string quartet has associations of high art and intellectualism, it has been a medium for diverse and different British composers. It also continues to inspire students, composers, and performers.

The project aimed to work with the widest possible range of those interested in the string quartet and music education, and to combine research with practical work and performance.

Diversity and the British String Quartet has been a collaboration between British music and music education specialists at the Oxford Faculty Of Music, the Villiers Quartet, contemporary composers, and schools.

Young people aged 14-18 at schools around the country have been involved, composing their own string quartets and working virtually over the last six months with professional performers, academics, and composers. On top of this work, the project has simultaneously evaluated the impact of the project on young people in terms of changing their perceptions of and relationship with classical music.

And the Villiers Quartet has commissioned five contemporary British composers to write ‘From Home’ quartets, exploring the experience of writing music in Britain in the current historical moment.

If classical music education is narrowed and defunded to the point of becoming an experience for those who can afford it, is inclusivity narrowed still further? Whose music is this, and what are the views of all those who have a stake in it?

Dr Joanna Bullivant

Dr Joanna Bullivant leads the project, which is supported by the TORCH programme. She believes the questions posed by the collaboration reach into the roots of our society. She says, ‘Increasing focus on STEM subjects in schools and universities, the global pandemic, and the Black Lives Matter protests have all raised important questions about the value of classical music performance and education in Britain.

‘If classical music education is narrowed and defunded to the point of becoming an experience for those who can afford it, is inclusivity narrowed still further? Whose music is this, and what are the views of all those who have a stake in it?’

Second year undergraduate and student mentor Chloe Green says, ‘The project facilitated important conversations and collaborations between diverse musicians in their processes of challenging preconceived notions about, and defining their own relationships to, the British string quartet tradition. It was a privilege to mentor the students as they developed their understandings of this tradition’s history and articulated their inspiring visions for its future.’

Graduate researcher and workshop participant Aaliyah Booker says, ‘I have learned a lot about composition and what it takes to write music for this type of ensemble. It has been fun doing research on the project and equally rewarding to be given an opportunity to play for the Villiers Quartet.’

For the Villiers Quartet, who guided the workshops with young people and commissioned the new quartets, this was a positive amongst the devastating and disruptive pause in performance caused by the pandemic.

Carmen Flores, violist, says, ‘We looked at string quartet composition from all angles - working with students, commissioning new works from our commissioned composers, and exploring repertoire of historical composers who were largely excluded from the mainstream story of British music.’

The live-streamed symposium (Monday 14 – Wednesday 16 June) is the culmination and public presentation of these activities through a series of talks, workshops, and performances.

Classical music has the potential to transform and enrich everyone’s lives, and we are committed to ensuring that those benefits are available to all. It promises to be a thrilling creative project

Professor Daniel Grimley

The symposium’s daily concerts will feature an array of rarely-heard British quartets, plus the world premiere performances of works by composers Florence Anna Maunders, Philip Herbert, Rob Fokkens, Alex Ho, and Jasmin Kent Rodgman. The student quartets, created during the project, will also be performed. Finally, expert speakers from the music industry and academia will address a range of issues in the history of the British string quartet and contemporary practice.

Dr Bullivant says, ‘This ambitious project has been a distinct learning curve for all of us, but hugely rewarding as we have been able to hear from so many different participants and voices on a subject that they are passionate about.’

And Dr Bullivant’s words are echoed by Professor Daniel Grimley, Deputy Head of Humanities, ‘Classical music has the potential to transform and enrich everyone’s lives, and we are committed to ensuring that those benefits are available to all. It promises to be a thrilling creative project.’

Diversity and the British String Quartet | TORCH | The Oxford Research Centre in the Humanities

Schools involved are: St Gregory the Great Catholic School, Oxford; St Marylebone School, London; Graveney School, London; Framingham Earl High School, Norfolk and Trinity Catholic School, Nottingham

It is easy to believe Melinda Mills was a very disruptive child. She is clearly a disruptive adult...and that has proven to be a very good thing indeed. Over the last year, it has been a valuable and evident quality as the Oxford professor of sociology and demography has provided sometimes controversial, often difficult to hear, but always research-based advice to government, business and the public on everything from face coverings and social bubbles to vaccine passports. This has not always won her friends, but it has helped inform and influence policy.

Putting social and behavioural sciences firmly at the table, Professor Mills knew her team (at the newly-established Oxford’s Leverhulme Centre for Demographic Science and from her European Research Council Advanced Grant) had a real role to play in fighting the pandemic.

It is important when looking at the impact of the pandemic not to forget ‘behaviours, social environment and population composition’; the sort of bread and butter work of social scientists...what will or will not work...what has been tried before, what people will think and how they will react

She explains it is important when looking at the impact of the pandemic not to forget ‘behaviours, social environment and population composition’; the sort of bread and butter work of social scientists, looking at who is in the population, what will or will not work with each group, what has been tried before and what people will think and how they will react.

‘It became quite clear we could make a contribution and we wanted to help,’ she says. ‘By being systematic, using different data and thinking and drawing from multiple scientific disciplines.’

As early as last March, the team set aside ‘regular’ work and turned attention to the pandemic. ‘With its interdisciplinary team, the Leverhulme Centre was ‘uniquely positioned’, she says, to provide the demographic data and research-based advice on the real world decisions and impacts of the pandemic and the policies being introduced to contain it.

As the world looked in fear at events in Italy, before the pandemic even reached the UK, the demographers had seen it coming, realising Italy’s ageing population would suffer greatly in the face of the coronavirus. The team were one of the first to clarify the value of demographic science in understanding the pandemic, in April 2020, with a widely cited article.

Before the pandemic even reached the UK, the demographers had seen it coming, realising Italy’s ageing population would suffer greatly in the face of the coronavirus

The next action they took was to set up an online ‘dashboard’, looking at the likely impact of the pandemic and potential hospital shortages in the UK. Using demographic data, such as age and ethnicity profile, Professor Mills’ team was able to predict which NHS trusts would be overwhelmed. One answer came back quickly: Harrow, in North West London. With its mixture of older residents and other social traits including density and ethnicity, it looked vulnerable – and so it proved.

‘We were able to predict [based on the data] where hospital beds would be under pressure. Our research was very granular. And that was just with basic demographic information. It had quite a bit of impact.’

After that, Professor Mills has not ducked difficult issues – however controversial and potentially uncomfortable.

‘I could have stayed on safe topics and I might have had a nice relaxing year,’ she says. ‘But I have never done that, [with my ERC research], and I thought we had a responsibility. I could see some opinions being voiced without evidence. We needed to provide balance and rigorous evidence-based research.’

Setting aside her plan for a once-in-a-career sabbatical, the expert in sociogenomics led her team to undertake unusually rapid research. Instead of taking months before data is published and more months trying to persuade policymakers of its value, they were sometimes asked to provide results in the space of 76 hours. And, based on this, policy changed in days.

Professor Mills has drafted major reports on face coverings [the evidence was quite clear and enacted by government in days], social bubbles [fed into policy internationally], misinformation [potentially dangerous], vaccine hesitancy and deployment [not to be dismissed] and vaccine passports [ethical and technical minefield]

Working on the Royal Society’s COVID-19 science in emergencies group, Professor Mills has drafted major research-based reports on face coverings [the evidence was quite clear and enacted by government in days], social bubbles [fed into policy internationally], misinformation [potentially dangerous], vaccine hesitancy and deployment [not to be dismissed] and vaccine passports [ethical and technical minefield].

She also served on several sub-groups of the UK government’s SAGE (Science Advisory Groups for Emergencies), focussing on behavioural insights, ethnicity and vaccines.

She says, ‘We have worked in tandem with policymakers, which has been very productive...the value of our work has been heard. We have made a difference.’

But putting her head above the parapet, has not been without risks and rewards. The director of the Leverhulme Centre has become a well-known social scientist. Her input has been sought by government, at home and overseas, by businesses and organisations. But, over the last year, she has researched the murky worlds of data trade, conspiracy theorists, anti-vaxxers, and bogus medics, speaking the truth to loud and sometimes powerful interest groups. And there are some who really have not liked what the research has found.

Professor Mills may be one of the few professors of demography globally to have received death threats because of her research. Some of it has been really nasty or what one journalist noted after seeing some material as ‘astonishingly abusive’.

Professor Mills may be one of the few professors of demography globally to have received death threats because of her research

But she was quick to note that the majority of the population acted incredibly responsibly. She says, ‘There was a fear that people would not adhere to some of the pandemic measures such as lockdown or wearing face masks or resist vaccinations, but the majority were actually highly compliant.’

Here she also argues that clear communications, tailored to different groups or local communities remains vital, but also dialogue to respect and hear concerns rather than only one-way passive and information-laden communications.

Melinda Mills, not looking very disruptive in the Canadian mountains.

Melinda Mills, not looking very disruptive in the Canadian mountains.Professor Mills’ capacity for disruption began early. As a farm girl growing up ‘in the middle of nowhere’ in Canada, she laughs as she recalls spending a lot of time in the hallway at school, [for being disruptive, attention seeking and talking].

This was no Archers’ storyline of farming misery and countryside complaints, though, but a tale of a frighteningly over-achieving family - perhaps going some way to explain Professor Mills’ nothing-daunted approach. Her farmer and teacher father went on to become a Canadian MP, her brother is a professor at a top US university and her sister is a leading designer.

‘It’s a kind of unusual family, but in a good way,’ she admits. And, despite her apparently inauspicious, academic beginning in the hallway, the young Melinda went on to study demography and sociology at the University of Alberta and then to take a PhD in Demography in the Netherlands, from where she came to Oxford in 2014 as a Statutory Professor at Nuffield College and the Department of Sociology.

She is baffled by some negative personal attacks, though. One journalist accused her of being like ‘Spock’.

‘I’m a Trekky,’ she laughs, pointing out that James T Kirk [William Shatner] is a fellow Canadian. But she says, ‘I always loved Spock and the Vulcan character. I like being very rational, systematic and non-emotional when I look at the evidence. I don’t see that is bad.’

I’m a Trekky...I always loved Spock and the Vulcan character. I like being very rational, systematic and non-emotional when I look at the evidence. I don’t see that is bad

The evidence provided by social sciences has proved its worth in the pandemic, as has the benefits of working across the disciplines at Oxford.

‘There was thinking that evidence was only valid if it came from a randomised control trial (RCT),’ she says. But it is different in social sciences, sometimes an RCT would not be an ethical or useful approach, says Professor Mills.

But, she points out, the data and research we draw from is peer-reviewed, systematic and accurate – and often based on very large representative samples, so thinking about what counts as valid evidence also needs to change.

There is still some way to go, she says, despite the relative success of the vaccine programme in the UK, there is concern over the rise of new variants. As a social scientist she recognises, ‘People are fatigued now on multiple levels. We are also experiencing an ‘infodemic’ and it’s difficult to process all the information.’

Demography is emerging from the pandemic as a powerful discipline and the Leverhulme Centre as the go-to place for research. Rather taken by surprise, Professor Mills admits, ‘I didn’t realise our approach was going to be so valuable....But national and international governments, organisations and businesses contact us now. And our work has energised and attracted a lot of young researchers. We hear from people around the world....A year and a half ago, there were eight people at the Leverhulme Centre, now there are around 30.’

With wide-ranging academic interests, she is most enthusiastic talking about the cross-disciplinary potential, adding, ’We have had support from organisations, including the Royal Society [which has published some of Professor Mills’ reports] and the British Academy and it is exciting to be in meetings with immunologists, engineers, computer specialists, it’s important for understanding social behaviour and serious problem solving.’

Later this month, Professor Mills will be taking part in the Brussels Economic Forum as one of eight advisors.

Later this month, Professor Mills will be taking part in the Brussels Economic Forum as one of eight advisors.Not one for a ‘quiet life’, later this month, Professor Mills will be taking part in the Brussels Economic Forum in her role as one of eight advisors in a High-Level Group convened by European Economic Commissioner Paolo Gentiloni, the former Prime Minister of Italy. She will be speaking amongst President of the European Commission Ursula von der Leyen, German Chancellor Angela Merkel, President of the European Bank Christine Lagarde, and the Prime Minister of New Zealand, Jacinda Arden.

A lesson exposed by the pandemic has been the deep inequalities, accelerated shifts to the digital economy, offering us a chance to reboot our thinking and planning

Professor Mills

Full of concern about the future of employment in a post-Covid world, which is at the heart of her European Research Council Advanced Grant, she says, ‘A lesson exposed by the pandemic has been the deep inequalities, accelerated shifts to the digital economy, offering us a chance to reboot our thinking and planning.’

Professor Mills speaks with considerable warmth about the flexibility and strength of her team at the Leverhulme and on her ERC project, ‘They’ve worked really hard and we have gotten to know each other very well – even though mostly remotely. That’s what you do when you bond.

‘It’s a diverse group, but it wasn’t hired to be diverse. They were the best people for the job.’

With every intention of boldly going further, Professor Mills concludes, ‘I’m very excited by the opportunities and talent at Oxford. There’s so much to offer.’

Two years ago, the Leverhulme Centre was launched with a £10 million grant.

Scientists at the University of Oxford have discovered that classical nova explosions are accompanied by the ejection of jets of oppositely-directed hot gas and plasma, and that this persists for years following the nova eruption. Previously, such jets had only been encountered emanating from very different systems such as black holes or newly collapsing stars.

A classical nova is the name given to an explosive event in our Galaxy. It has been known for decades that when a nova erupts, its brightness can increase by several orders of magnitude and can transform an undetectable star into an object that can be seen by the naked eye. This huge increase in brightness happens when matter is ripped away from one star onto the hard surface of a companion star, a compact object known as a white dwarf. The matter accreted onto the white dwarf becomes extremely hot and dense, providing the right conditions to synthesize heavier elements, a process known as thermonuclear runaway.

It’s amazing that jets emerge from these remarkable objects, in spite of the turbulence of a nova detonation

The Global Jet Watch, led at the University of Oxford by Professor Katherine Blundell, comprising telescopes separated in longitude around the world to follow sub-day variability in the Galaxy made this discovery possible. The team published this finding in early 2021, reporting the initial discovery of jets in a classical nova that had erupted during the pandemic lockdown of 2020 and was subsequently followed intensively with time-lapse spectroscopy with the Global Jet Watch in the days, weeks and months that followed.

In a second paper published by the Royal Astronomical Society, the team has demonstrated that the exact same behaviour is exhibited by four out of four classical novae that the Global Jet Watch has been monitoring. This collection of four eruptions includes different types of classical novae (including one hybrid type) suggesting that jets are a likely outcome for the classical nova phenomenon in general.

In a second paper published by the Royal Astronomical Society, the team has demonstrated that the exact same behaviour is exhibited by four out of four classical novae that the Global Jet Watch has been monitoring. This collection of four eruptions includes different types of classical novae (including one hybrid type) suggesting that jets are a likely outcome for the classical nova phenomenon in general.

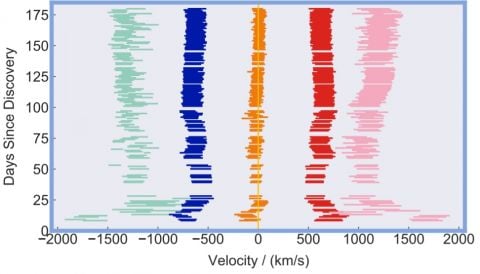

Graphic shows: Illustration of how the speeds along our line-of-sight to the nova that detonated in July 2020 changed in the days that followed its eruption. The changing speeds along our line-of-sight are believed to be because the directions along which the jets of hydrogen are squirted change with time, a phenomenon known as precession.

Besides now being able to study the phenomena of jets, their launch, their propagation and their precession in a new way, the discovery is also a significant advance in understanding the influence of classical novae themselves on our Galaxy, the Milky Way. The fact that they can propagate hot gas far, far away from the site of the explosion itself has implications for the enrichment of the inter-stellar medium within our Galaxy with the new elements synthesised in the course of the explosion. Further exploration and investigation of these implications is planned.

Dominic McLoughlin, the graduate student who had been investigating the time-series nova data, said; ‘The nova that erupted in July 2020 enabled us to crack the code. Discovering jets in the immediate aftermath of classical nova eruptions means we can now study them as they start launching and precessing – it’s not understood how jets actually get launched in general, despite the fact they happen all over space.’

Professor Katherine Blundell, who designed and instigated the Global Jet Watch, said: 'It’s amazing that jets emerge from these remarkable objects, in spite of the turbulence of a nova detonation – and it’s also amazing that the Global Jet Watch has persisted robustly throughout the turbulent times of lockdown. This opens up a whole new way to study the jet phenomena which is ubiquitous across the Universe.’

The nova that erupted in July 2020 enabled us to crack the code

The Global Jet Watch was designed to accomplish two important goals. One of these goals was to be able to provide time-lapse spectroscopy of evolving and dynamic systems in our Galaxy, an important class of which are the so-called micro-quasars which can be regarded as scaled-down, speeded-up models of quasars in the distant Universe. These new results demonstrate its effectiveness in following different types of optical transients as well as its resilience at a time when in-person visits to the observatories are not possible.

Professor Katherine Blundell said: ‘This discovery did not come about because of detailed plans and presumptions about the way the Universe is, but instead as a fun, auxiliary project adjunct to the main research programmes of the Global Jet Watch. Being open to exploring the Universe in new ways invariably seems to produce new insights into its richness and inner workings.’

The second goal of the Global Jet Watch was to engage young people in developing countries, especially girls, into science and technology through the doorway of astronomy which is a gateway and exemplar of so many areas of high-level science and engineering. In non-lockdown times, the schools around the world that host the observatories are free to use the telescopes before local bedtime.

The second goal of the Global Jet Watch was to engage young people in developing countries, especially girls, into science and technology through the doorway of astronomy which is a gateway and exemplar of so many areas of high-level science and engineering. In non-lockdown times, the schools around the world that host the observatories are free to use the telescopes before local bedtime.

The Global Jet Watch uniquely combines excellence in science with empowerment for school students, around the world; astronomy is a gateway to science for so many

The experience of controlling the telescopes, operating the cameras and exploring and capturing the night sky has proved to be a pivotal experience for many. Already some of the first students to have used the telescope at their school have gone on to study science and/or engineering at colleges and universities in their countries.

Brian Schmidt, the Vice-Chancellor of the Australian National University and Nobel Prize winner in 2011, said: ‘This discovery will change the way we think about classical novae. The Global Jet Watch uniquely combines excellence in science with empowerment for school students, around the world; astronomy is a gateway to science for so many.’

A group of students control the telescope

A group of students control the telescope

For a short video about the Global Jet Watch, please see: https://www.globaljetwatch.net/news/what-is-the-global-jet-watch/

To date, over 3.5 million people have died from Covid-19. Understanding its origins, with a view to preventing any future such pandemics, is therefore of global importance. Covid-19, known formally as SARS-CoV-2, is a coronavirus, and historically these have come to afflict humans through spill-over from wildlife sources. This was the case with the Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) outbreak in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, in 2012, spilling-over from dromedary camels, killing 858 people; similarly the SARS-CoV epidemic (for which there is still no cure) that began in Guangdong in 2002 and killed 744 people, spilled-over from palm civets as an intermediary, transferring infection from cave-dwelling horseshoe bats.

We had been gathering data collected from across Wuhan’s wet markets…which put our team in the right place at the right time to document the wild animals sold in these markets in the lead up to the pandemic

Not surprisingly then, the finger of blame has been pointed at wildlife trade in the wet markets of Wuhan, Hubei, China, where this Covid-19 outbreak seems to have originated. Candidate species include bats, which are definitive hosts brewing coronaviruses, and both pangolins and palm civets as potential intermediaries; although the most recent genetic data suggest that the variant found in these latter species isn’t quite similar enough to the human variant to be a totally convincing source. Nevertheless, through 14th Jan to 10th Feb this year the World Health Organization (WHO) sent an investigative team to Wuhan, where part of their remit was to try to ascertain, post hoc, what animals were being sold in markets prior to closures. Their report was inconclusive, but drew attention to the particular need to monitor bat and pangolin trading.

Our investigation found that both bats and pangolins had an alibi – neither was there!

Working with our colleagues based at China West Normal University, Nanchong, and Hubei University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Wuhan, Xiao Xiao and Zhao-Min Zhou on the ground in China, the WildCRU team had been gathering data collected from across Wuhan’s wet markets through May 2017 and November 2019. This research, begun before Covid-19 focused a spotlight on these markets, was actually motivated by a study of tick-borne (no human-to-human transmission) Severe Fever with Thrombocytopenia Syndrome, which put our team in the right place at the right time to document the wild animals sold in these markets in the lead up to the pandemic. Our investigation, published today in Nature-Scientific Reports, found that both bats and pangolins had an alibi – neither was there!

Caged marmots above a cage containing hedgehogs, Huanan seafood market prior to closure

Caged marmots above a cage containing hedgehogs, Huanan seafood market prior to closureWith these huge concentrations of diverse species under one roof, while we discovered no evidence supporting original spill-over from candidate bats or pangolins in Wuhan, it would seem but a matter of time before some other unwelcome disease might skip into the human population. Indeed it is estimated that around 70% of all diseases afflicting people originate in animals, think Avian Influenza, HIV, Ebola, etc.

Commendably, with this risk in mind, on the 26th of Jan 2020, China’s Ministries temporarily banned all wildlife trade as a precautionary step until the COVID-19 pandemic concludes. Subsequently, on 24th Feb 2020, they permanently banned eating and trading terrestrial wild (non-livestock) animals for food. These interventions, intended to protect human health, redress previous trading and enforcement inconsistencies, will have collateral benefits for global biodiversity conservation and animal welfare, and will hopefully prevent some future tragedies.

Professor David Macdonald is Director of WildCRU, part of the Department of Zoology, University of Oxford

- ‹ previous

- 18 of 247

- next ›

From research to action: How the Young Lives project is helping to protect girls from child marriage

From research to action: How the Young Lives project is helping to protect girls from child marriage  Can we truly align AI with human values? - Q&A with Brian Christian

Can we truly align AI with human values? - Q&A with Brian Christian  Entering the quantum era

Entering the quantum era Can AI be a force for inclusion?

Can AI be a force for inclusion? AI, automation in the home and its impact on women

AI, automation in the home and its impact on women Inside an Oxford tutorial at the Museum of Natural History

Inside an Oxford tutorial at the Museum of Natural History  Oxford spinout Brainomix is revolutionising stroke care through AI

Oxford spinout Brainomix is revolutionising stroke care through AI Oxford’s first Astrophoria Foundation Year students share their experiences

Oxford’s first Astrophoria Foundation Year students share their experiences DPhil student, Frankco Harris, reflects on his unique journey to Oxford and future plans

DPhil student, Frankco Harris, reflects on his unique journey to Oxford and future plans Oxford undergraduates reflect on their first term

Oxford undergraduates reflect on their first term