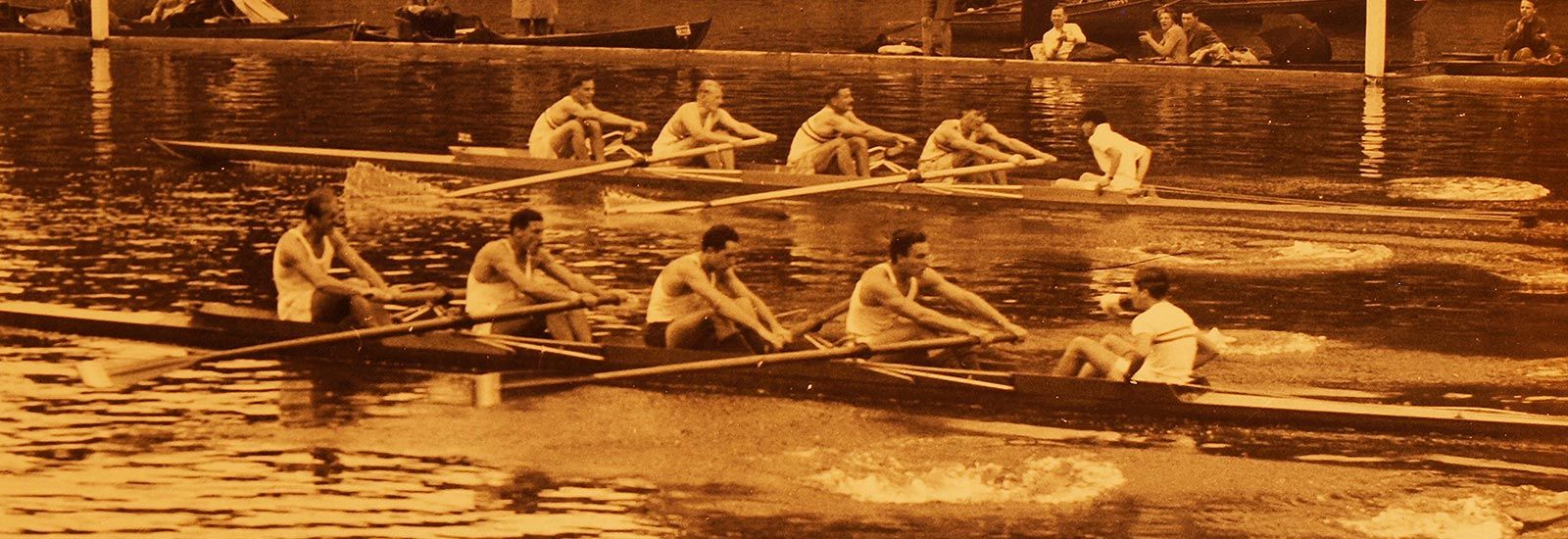

London 1948

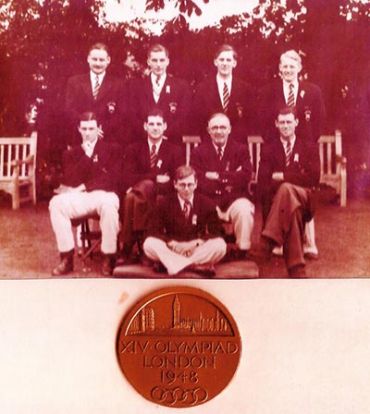

Oxford alumnus Tim Healey, who participated in the Men's Coxed four at the 1948 Olympics, has kindly shared some photos with us.

1948 Olympics portraits medal

1948 Olympics portraits medalBack row from left to right: The crew of the 1948 Coxed IV

R M Collins; W J H Leckie; A J R Purssell; W W Woodward

Front row from left to right: The coaches of the Coxed IV

A D Rowe (Sculler in the 1948 Olympics); J H T Wilson (Winner of the gold medal in the Coxless pairs in the 1948 Olympics); A McCulloch (Winner of the silver medal as a sculler in the 1908 Olympics); W G R M Laurie (Winner of the gold medal in the coxless pairs in the 1948 Olympics and father of the actor Hugh Laurie)

Sitting at the front of the photo:

J A D Healey (Cox of the 1948 Olympic Coxed IV)

The rocky road to Wembley

Oxford alumnus Geoff Tudor remembers the 1948 Olympics – the last time London hosted the Games.

'Some of us reached the 1948 Olympics by the strangest of routes; one of our sprinters was a cricketer by choice! My own main sport was boxing, and I’d done no track running until two years before the Olympics, and no steeplechasing until six months before.

Here’s a summary of my rocky road to Wembley.

Childhood

I’ve no memories of being especially aggressive at school, but boxing seemed to come naturally, and soon I won a place in the school team for the lowest weight. Cross-country I also enjoyed, but fate determined that there was no opportunity to win a place in one of the school teams.

Oxford alumnus Geoff Tudor

Oxford alumnus Geoff TudorPeople born in the past 40 years have no conception how much the early life of us older folk was disrupted by illness. Every Spring term many of us would be laid low by measles, German measles, chicken-pox or mumps – warded off nowadays by early jabs. Three years in succession, when the cross-country was held, I was in the school sanatorium with rash or spots or swelling. Only in my last year was I free from illness, ran in the race and finished the winner.

The Second World War

War had started by now, so then it was the army and more boxing – first while training as a Gunner on Salisbury Plain, then as a Lieutenant in a Mountain Artillery Regiment in Scotland. To load guns onto mules men had to be burly and tall, so I happened to be one of the very few who could box under 10 stone – provided I could lose four pounds!

The boxing match was just after Christmas, so not even the limited wartime indulgences were enjoyed that year. After a Turkish bath and a 24-hour fast I just made the weight and won by a knock-out in the first minute. (A welcome result for what proved to be my last fight, but rather a poor return for all those days of sweating and fasting: hours of effort for a few seconds of glory!)

Then it was off to fire our guns in Holland and Germany, so now it was bombarding rather than boxing.

From boxing to cross-country

Geoff Tudor winning the 880x v Queen's Belfast on 20 May, 1946 at Iffley Road

Geoff Tudor winning the 880x v Queen's Belfast on 20 May, 1946 at Iffley Road

Back from the war and starting at Oxford, first thoughts were for taking up boxing again, but after years of open-air life the confines of a gym were stifling. So it was back to cross-country once more, and a good enough result in the trials to win a place in the Oxford team. Then 1946 came round, and we needed to raise a team for the Track and Field match against Cambridge. Oxford had a dire shortage of runners, so we were all drafted down to the track to see how we could perform. Strangely enough I found myself in the team for the 880 yards: never thought I could work up that sort of speed!

Next year, 1947, was the year of the Great Snow! At Oxford it lasted from 27 January to 10 March. This allowed us just two weeks of training on the track before the Cambridge match on 22 March. (This time I was drafted for the 3 miles – not surprisingly, a very slow race.)

Geoff Tudor (3rd from right) and Peter Curry (2nd from right) training at Iffley Road in the snow of 1947

Geoff Tudor (3rd from right) and Peter Curry (2nd from right) training at Iffley Road in the snow of 1947

Once again, that summer, it was a matter of ‘fitting in’ wherever a spare runner was needed – even a 440-yards relay once or twice. It was a relief to return to cross-country that autumn, and by now I was Captain. Two years running we’d been narrowly beaten by Cambridge and were determined to win this time. We pioneered a much more demanding course and built up enough support to field three teams.

The power of the press

The season developed well, with wins against three good clubs – Orion, Blackheath and Finchley. These wins caught the attention of the Daily Telegraph correspondent who wrote an enthusiastic report:

"Because of the keenness of their Captain, I prophesy a wonderful season for the Oxford University Cross-Country Club. Tudor is himself a remarkable runner – quite obviously he has speed and stamina. I wonder why the British Olympic people do not persuade him to try his hand at steeple-chasing with next year’s Olympics in mind. New blood is badly needed in steeple-chasing, and Tudor strikes me as having distinct possibilities if he can learn to hurdle reasonably well."

The following week came the official invitation to train for the Olympic Steeplechase. Talk about the power of the press!

I, along with my fellow Oxford runner, Peter Curry, was invited to train for the 3,000m Steeplechase. At first this seemed impossible to believe, way beyond the range of our ambition. Yet a few days later things began to happen. A film crew came to Oxford to portray this aspect of Olympic preparations. “We want to picture the two of you coming through Tom Gate at Christ Church – that will make a good picture: wearing your gowns of course.” We objected that when walking round College, we would not normally be wearing gowns. “Folk are not to know! It will look authentic: that’s what we want!” So we were ‘shot’ walking about in gowns, and later in running gear down at the track.

The Finals hurdle

After this brief flurry of activity all thought of the Olympics faded very much into the background. During those post-war years there were shortened courses with Finals in November for those coming back from war service. So there was an intensive week of head-scratching and pen-pushing and a round of farewell-parties. None of this was very good preparation for the Oxford v Cambridge Cross-Country which we won by a record margin – though not due to my own below-par performance. Christmas followed, and serious thoughts of the Olympics began again with a visit to my coach, Bill Thomas, at Herne Hill in mid-January. He was 75, but still an active runner and an enthusiast for ice-cold showers; nothing else was available so we followed his lead – but with markedly less enthusiasm! So began my official Olympic training – just over six months before the event took place. I suppose there were six visits to Herne Hill in all – a tedious journey in crowded suburban trains with long waits on draughty suburban platforms. Energy expended on the training was replenished with chocolate-coated raisins from slot-machines.

The loneliness of the steeple-chaser

There were two considerable problems in training for the Steeplechase:

1) There were hardly any steeplechase courses available on which to train;

2) There were no steeplechase events in which to gain experience. Hurdling – a totally new skill to master – was practised at home over a mock-up hurdle fashioned from scrap timber. A diagonal course across the lawn gave just enough space, though there had to be a rapid slow-down among the trees at the far end. Then one loped back to the beginning and started all over again: not an ideal way of building up technique.

What comes back to one was the isolation and loneliness of the whole endeavour. By then I was working as a Temporary Lecturer in History at Sandhurst Military College. This provided a track to train on and occasional company on training runs. It also provided an opportunity to watch the classic film of the 1936 Berlin Olympics – more a tribute to Nazi ideology than to Olympic ideals.

Billy Butlin to the rescue

Then in mid-April came a three-day training and team-building gathering. The total budget for financing the 1948 London Games was less than a million pounds, so there was nothing to spare for financing this kind of jollification. Billy Butlin came to the rescue, providing accommodation free of charge at his Clacton Holiday Camp.

Film-goers – conditioned by the award-winning Chariots of Fire (1981) – may well have a faulty image of our preparations back in 1948. There was no back-slapping and fun-and-games in a fashionable hotel, and I can remember no team-building runs along the sands to the sound of stirring music!

In Chariots of Fire the team ran along golden sands beside a sun-sparkled sea. At Clacton it rained, and we splashed our way through the puddles along a soggy promenade, then back to our bangers and mash or macaroni cheese. After a brief spell of ‘civvy’ life it was almost like being back in the army again!

Competition time

Back then to lonely training runs and weekend competitions. In mid-May there was an opportunity to run a steeplechase course for the first time. This was a help, but I was to discover later that it was not equipped with the heavy, Olympic-style, hurdles. Not till 7 June was there a visit to the White City and a chance to try out its steeplechase course. On 12 June came the Southern Counties Steeplechase and a second place. No more steeplechase contests were available, so it was a matter of finding mile or half-mile races to keep in trim.

3 July arrived, and the AAA Championships at the White City. A breakdown on the Tube left just time enough to change but no time for a warm-up: the rush to get there probably formed an effective substitute! Fellow Oxford cross-country runner, Peter Curry, just pushed me into second place, and four days later came the official invitation to form part of the Olympic team. No more opportunities to train over a steeplechase course: it was a matter of entering what happened to be available around London or as far away as Birmingham. There were half-mile relays, a three-quarter mile race and a three-mile race.

Austerity Olympics

July 1948 was less than three years after the end of the Second World War. Many parts of London still lay in ruins, and would-be athletes were returning in dribs and drabs from war service in many parts of the world.

Britain had originally been awarded the running of the 1944 Games, which proved to be a time when war still flared worldwide. Could we possibly achieve the next date of 1948? Urgent meetings were held and many heads were wagged. Much of the press, it seemed, was against spending money on such ‘frivolity’ when funds were needed for house-building and other urgent tasks.

For a time it seemed doubtful whether the Games could go ahead – even in a much-shrunken form. It seems that King George VI played a crucial role in stressing the morale-building significance of going ahead as planned. The financial figures seem hard to credit today: total budget of £800,000; £1,000 received from BBC for broadcasting rights.

The big day arrives

The days passed – much too slowly. There was the Official Opening by King George VI and crowds of pigeons. Then came 3 August and the Steeplechase heats.

I watched my friend Peter Curry run – he was not among the qualifiers. I came to a hasty decision. I would run faster than that – or bust in the attempt. I bust! The race was seven and a half laps of the track. After five laps my time was eight seconds faster than Peter’s. I put on a spurt and passed one of the other runners. The cheer was deafening – but by then I’d given it my all. On the sixth lap I was fading and on the seventh I wondered whether I’d collapse into the water-jump! I staggered round to finish last in the heat.

It’s always the spectator who sees thing most clearly! Watching the event was fellow Oxford athlete and future editor of the Guinness Book of Records, Norris McWhirter. Next day he sent the following report. ‘Your first five laps went at a killing pace, and I knew immediately you had done a 63.9 first lap: it would be impossible for you to keep it up.’ How right he was!

That was my last steeplechase: it was back to cross-country and an occasional run on the track. I’d learnt something, however. Eight months was too short a time to train for that gruelling race. Chris Brasher won the Steeplechase in Melbourne in 1956: he’d been at it, not for eight months, but for eight years!'